13 Feb 2018

Hailed by some as the future of clean energy, nuclear fusion is an exciting and promising area of research supported in the UK by the Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) – an organisation within the UK government responsible for the establishing the UK as a leader in sustainable nuclear energy.

JET’s MASCOT telemanipulator allows scientists to remotely operate inside the vessel. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Its core mission is for the commercial development of nuclear fusion power, a feat yet be to achieved, with research still ongoing into a feasible, large-scale reactor to convert energy from nuclear fusion into electricity.

An untapped source

Nuclear fusion occurs between two or more charged particles during a high-energy collision, with the resulting reaction producing a large amount of energy that could, at least theoretically, be converted into electricity. This reaction is only possible at extremely high temperatures and pressures, and is the process the Sun uses to generate energy.

Here on Earth, nuclear fusion is difficult to replicate, with researchers struggling to match the energy produced with the high amounts of energy needed to start the reaction, in order for it to become a feasible form of energy to power the world.

To date, the largest successful nuclear fusion reactor is the result of the Joint European Torus (JET), managed by the UKAEA at the Culham Science Centre, Oxford, UK, and used by more than 40 other European research laboratories.

Hosted at the centre since its conception in 1973, the EU project has produced the only operational reactor that can generate energy from nuclear fusion.

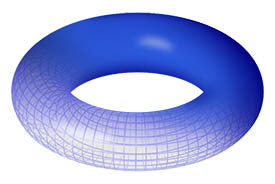

The JET is a tokamak – a device designed around the centrally placed fusion plasma, a fourth fundamental state of matter after solid, liquid, and air, that does not exist freely on Earth, containing the charged particles essential for nuclear fusion to occur.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Although other possibilities are still being explored, the tokamak is the leading candidate for a commercially viable nuclear fusion reactor and its design is the basis for JET’s successor.

Making history

In 2025, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) will run its first experiment, and if successful will be the world’s largest operating nuclear fusion reactor – ten times the size of any other in the world, producing upwards of 500MW of power.

A collaborative effort between 35 nations – China, India, Japan, Korea, Russia, the US, and all 28-member states of the EU – the ITER is the EU’s successor project to JET. Based in Provence, southern France, the ITER is self-championed as ‘one of the most ambitious energy projects in the world today’.

By 2025, ITER will produce its first plasma, later adding tritium and deuterium – a combination with an extremely low energy barrier – in 2035 to generate energy. If successful, the work on the ITER will confirm the feasibility of nuclear fusion as a large-scale, carbon-free energy source.

Future uncertainty

But with Brexit on the horizon, many have questioned the likelihood of the UK’s participation in the project, despite the UKAEA’s essential work in supporting the success of JET and continued commitment to investing in the project.

Director of ITER, Bernard Bigot, has said his concerns lie with the extension of Joint European Torus (JET) – ITER’s predecessor which is due to end this year. ‘If JET ends after 2018 in a way that is not coordinated with another global strategy for fusion development, clearly it will hurt ITER’s development,’ he said. ‘For me it is a concern.’

Creating a new base for training and research would be costly, and is unlikely to be favoured, and those involved in Euratom, the EU’s atomic energy community and main source of JET funding, are now worried that the seven-year gap between the projected end of funding to JET and the first experiment of ITER may damage the latter’s prospects of success.

In a statement on the future of JET, the UK government said: ‘The UK’s commitment to continue funding the facility will apply should the EU approve extending the UK’s contract to host the facility until 2020.’

With hopes for JET’s funding to continue until at least 2023, and the UK government announcing its intentions to leave Euratom last year, the future of the UK’s ability to compete in the nuclear sector rests on the progress of Brexit negotiations in the coming months.

By Georgina Hines