What is so special about rainbow chard pigments, and what does this tasty plant have in common with cacti? The SCI Horticulture Group explains all, ahead of their appearance at BBC Gardeners’ World Live in Birmingham from 16-19 June.

The origins of chard

Chard (Beta vulgaris, subspecies vulgaris) is a member of the beetroot family and is grown for its edible leaf blades and leaf stems. Chard, sugar beet, spinach and beetroot have all been domesticated from the same wild ancestor species – sea beet (Beta vulgaris, subspecies maritima). Another food crop from the same botanical family is quinoa.

The term chard comes from the 14th century French word carde, which means artichoke thistle.

Nutritional properties

Chard's leaves are a valuable source of mineral nutrients, with a normal serving of 100g containing: 24% of our daily magnesium needs, 17% of iron, 16% of manganese, and 12% of both potassium and sodium. The same portion can provide 22% of our daily vitamin C needs, 13% of vitamin E, and 100% of our vitamin K.

>> What gives chillis their heat? The SCI Horticulture group has explored the weird and wonderful world of chillis.

The edible petioles (leaf stems) of Swiss chard are typically white, yellow, or red. Lucullus and fordhook giant are cultivars with white petioles. Canary yellow has yellow petioles and red-ribbed forms include ruby chard and rhubarb chard. Rainbow chard is a mix of coloured varieties, often mistaken for a variety unto itself.

The pigments that produce these colours belong to a special group – known as the betalains. These pigments are found only in species of one small section of the plant kingdom called caryophyllales. The pigments in the rest of the plant kingdom have different chemical structures, made up of only carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, whereas the betalain chemical structures also contain nitrogen.

Rainbow chard contains betalains, as do cacti, pokeweed, and (above) bougainvillea.

The many uses of chard pigments

The colourful pigments in plants not only contribute to the beauty of our gardens – they advertise the presence of flowers to pollinators or fruits to dispersal agents. Others deter herbivores by tasting bitter or act as a sunscreen to protect from strong ultraviolet light.

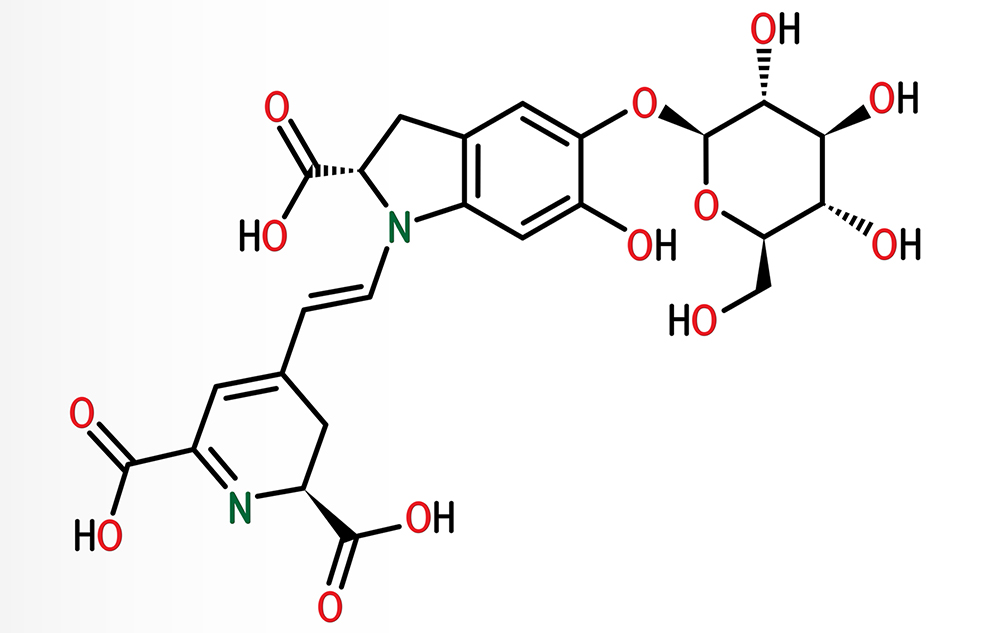

The vivid pigments found in chard are particularly useful. Betanin is the best-known pigment from this group and gives rise to the striking colour of beetroot. It is used commercially as a natural food dye, can help preserve food, and contains antioxidant properties.

Betanin, the pigment that makes beetroot (and poop) red.

Some people are unable to metabolise betanin, which gives rise to a phenomenon known as beeturia – where human waste is coloured red by the betanin.

Cooking with chard

When cooking with chard, it can be treated as two separate vegetables – the leafy part and the crunchy petiole. Blitva is a traditional Croatian dish made from the leafy part, often cooked along with potatoes and served with fish.

Blitva is made with chard, potato, olive oil, and garlic.

Chard stalks sautéed with lemon and garlic forms another popular side-dish, while lovers of Italian cuisine can turn rainbow chard into a pesto with pine nuts, parmesan and basil.

Find us at BBC Gardeners’ World Live

From 16-19 June, the SCI Horticulture Group will tell the public all about the hidden chemistry behind their favourite fruit and vegetable plants at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham for BBC Gardeners’ World Live. If you’re curious to learn all about rainbow chard, chillis, and strawberries, pop by and say hello!.

>> Written by the SCI Horticulture Group and edited by Eoin Redahan. Special thanks to Neal Price from Chillibobs, Martin Peacock of ZimmerPeacock, Hydroveg, and The University of Reading Soft Fruit Technology Group for supporting the work of the SCI Horticulture Committee at BBC Gardeners’ World Live.

>> The SCI Horticulture Group brings together those working on the wonderful world of plants.

Which molecules give strawberries their distinctive smell, how are experts using different types of light to grow them all year round, and just how many of them do we eat? The SCI Horticulture Group told us all about this beloved fruit ahead of their appearance at BBC Gardeners’ World Live in Birmingham from 16-19 June.

Where did strawberries originate?

The woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) was first cultivated in the 17th century, but the strawberry you know and love today (Fragaria x ananassa) is actually a hybrid species. It was first bred in Brittany, France, in the 1750s by cross-breeding the North American Fragaria virginiana with the Chilean Fragaria chiloensis.

The strawberry is a member of the rose family, as are many other popular edible fruits such as apples, pears, peaches, and plums. It is the most commonly consumed berry crop worldwide.

People in the UK consume an average 3kg of strawberries every year. Perhaps a certain sporting event has something to do with it…

How many do we eat?

A staggering 9 million tonnes of strawberries are produced globally each year, and their popularity certainly extends to UK shores, and not just during Wimbledon. In the UK alone, the average per capita consumption of strawberries is about 3kg a year!

Domestic strawberry production provides almost all the required fruit for the UK market from March to November; and in 2020, 123,000 tonnes of strawberries were produced within the UK.

This stands in stark contrast to the 50,000 tonnes produced in 1985, when UK strawberries were only produced during June and July. Researchers are currently trying to extend the UK growing season to all year round.

She certainly likes the smell of strawberries, but what gives them that distinctive aroma?

What about the chemistry of their distinctive smell?

The characteristic strawberry aroma consists of many different volatile organic chemicals – more than 360 have been observed in fresh strawberries. Which molecules are present, and in what concentrations, depends on the particular cultivar and how mature or ripe it is.

The most common kinds of chemical are furanones and esters. Esters (such as methyl butanoate) account for more than one third of the observed molecules and 25–90% of the volatiles from any one cultivar.

These molecules are responsible for the fruity and floral notes of the aroma. The most characteristic furanone that gives rise to the characteristic strawberry odour is DMHF.

Pictures like this only increase demand for strawberries out of season.

How to produce strawberries all year...

To optimise strawberry growing conditions, researchers are investigating the influence of temperature, photo-period (response to daily, seasonal, or yearly changes in light and darkness), growth hormones, night-break lighting and CO2 enrichment on flowering and fruiting timing, yield, and quality.

Optimal chilling models are also being developed for both June-bearers and ever-bearers. Critically, a careful and detailed evaluation of the environmental and economic costs of producing winter UK strawberries compared to imports is being undertaken.

Extending the growing season in the UK would have a number of benefits, such as; meeting the increasing demand for out-of-season strawberries while increasing food security, reducing food miles, contributing to public health, providing continued employment, and supporting sustainable farming.

>> Are you a keen gardener? Our resident gardening expert, Geoff Dixon, provides plenty of gardening tips for you on the SCIBlog.

Improving the fruit's nutrient profile

The nutrient content of strawberries is dependent in part on the plant’s growing conditions. The interaction between light intensity and root-zone water deficit stress is being examined to improve berry nutrient content. Researchers are also investigating how to apply this to commercial strawberry production in total environment-controlled agriculture systems.

See how a college in Finland is harnessing LEDs to power a vertical strawberry farm!

LED light colour and strawberry growth

Light emitting diode (LED) lighting increases yields in out-of-season strawberry production. LEDs have a higher energy efficiency than traditional horticultural lighting and come in a range of single colours with varying efficiencies and effects on plant growth.

Red LEDs convert energy into light (and drive photosynthesis) most efficiently, followed by blue, green, and far-red, respectively. However, red light alone is not sufficient for optimum plant growth. Blue light controls flowering, promotes stomatal opening (pores found in various parts of the plant), inhibits stem elongation, and increases secondary metabolites (organic compounds produced by the plant), thereby improving flavour.

Additional green LEDs, which appear white, improve visibility for workers. These lights can also penetrate deeper into the plant canopy, improving photosynthesis. Far-red light produces shade avoidance responses such as canopy expansion and earlier flowering, which can be beneficial for increased light capture and earlier fruiting.

>

>Confirmed strawberry.

Who is carrying out strawberry research in the UK?

The Soft Fruit Technology Group at the University of Reading is just one of the institutions providing research to support the UK strawberry industry. The main areas of research are plant propagation, crop management, and production systems.

Find us at BBC Gardeners’ World Live

From 16-19 June, the SCI Horticulture Group will tell the public all about the hidden chemistry behind their favourite fruit and vegetable plants at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham for BBC Gardeners’ World Live. If you’re curious to learn all about strawberries, chillis, and chard, pop by and say hello!

>> Written by The SCI Horticulture Group. Special thanks to Neal Price from Chillibobs, Martin Peacock of ZimmerPeacock, Hydroveg, and The University of Reading Soft Fruit Technology Group for supporting the work of the SCI Horticulture Committee at BBC Gardeners’ World Live.

What makes chilli peppers so spicy and how do they help with pain relief? The SCI Horticulture Group explained all ahead of their appearance at BBC Gardeners’ World Live in Birmingham from 16-19 June.

This June, the SCI Horticulture Group will tell the public all about the hidden chemistry behind their favourite fruit and vegetable plants. One of the main plants they will feature at the National Exhibition Centre is the humble chilli pepper – and these famous fruit-berries conceal more secrets than you might think…

Where does the chilli originate?

The chilli pepper (Capsicum spp.) is a member of the Solanaceae, the plant family that includes edibles such as potatoes, tomatoes, aubergines, but also poisonous plants such as tobacco, mandrake, and deadly nightshade.

Who brought the chilli pepper to these shores?

The chilli was brought to Europe in the 15th century by Christopher Columbus and his crew. They became acquainted with it on their travels in South and Central America and, shortly thereafter, to India via the Portuguese spice trade.

How varied is the genus?

Of the 42 species in the capsicum genus, five have been domesticated for culinary use. Capsicum annuum includes many common varieties such as bell (sweet) peppers, cayenne and jalapenos. Capsicum frutescens includes tabasco. Capsicum chinense includes the hottest peppers such as Scotch bonnet. Capsicum pubescens includes the South American rocoto peppers, and capsicum baccatum includes the South American aji peppers.

From the five domesticated species, humans have bred more than 3,000 different cultivars with much variation in colour and taste. The chilli and bell peppers that we eat are the fruit – technically berries – that result from self-pollination of the flowers.

>> The SCI Horticulture Group brings together those working on the wonderful world of plants.

And we eat a lot of them?

Today, chilli peppers are a global commodity. In 2019, 38 million tonnes of green chilli peppers were produced worldwide, with China producing half of the total. Spain is the largest commercial grower of chillies in Europe.

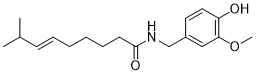

Capsaicin helps give chilli peppers their heat

What makes chillies hot?

Capsaicin is the main substance in chilli peppers that provides the spicy heat. It binds to receptors that detect and regulate heat (as well as being involved in the transmission and modulation of pain), hence the burning sensation that it causes in the mouth.

In humans, these receptors are present in the gut as well as the mouth (in fact, throughout the peripheral and central nervous systems) – hence the after-effects of eating too much chilli. Capsaicin, however, is not equally distributed in all parts of pepper fruit. Its concentration is higher in the area surrounding the seeds.

>> Get tickets for Gardeners’ World Live 2022 and pop by our stand to say hello!

How do you measure chilli heat?

The Scoville Heat Unit Scale is used to classify the strength of chilli peppers. Scoville heat units (SHU) were named after American pharmacist Wilbur Scoville who devised a method for rating chilli heat in 1912.

The ludicrously hot Dragon’s Breath chilli

This method relied on a panel of tasters who diluted chilli extract with increasing amounts of sugar syrup until the heat became undetectable. The greater the dilution to render the sample’s heat undetectable, the higher the SHU rating. Pure capsaicin measures 16,000,000 SHU.

The capsaicin content of chilli peppers varies wildly, as is reflected in the SHUs of the peppers below:

- Bell (Sweet peppers) = 0 SHU

- Jalapeno = 5,000 SHU

- Scotch Bonnet = 100,000 SHU

- Naga Jolokia = 1,040,000 SHU

- Carolina Reaper = 1,641,183 SHU

- Dragon’s Breath = 2,480,000 SHU

Dispersal vs. protection – why do chillies contain capsaicin?

The seeds of chillies are dispersed in the wild by birds who do not have the same receptors as mammals and, therefore, are unaffected by capsaicin. Perhaps chillies have evolved to prevent mammals from dispersing their seeds?

Capsaicin has also been shown to protect the plant against fungal attack, thus helping the fruit to reach maturity and the seeds to be dispersed before succumbing to rot. This antifungal property can also be put to good use in helping to preserve foods for human consumption.

How did chilli help win a Nobel Prize?

Capsaicin was pivotal in the research that led to the award of the 2021 Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine to David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian for their discoveries of receptors for temperature and touch.

The two US-based scientists received the accolade for describing the mechanics of how humans perceive hot, cold, touch, and pressure through nerve impulses. The research explained at a molecular level how these stimuli are converted into nerve signals, but the starting point for the study was work with capsaicin from the humble chilli pepper.

Capsaicin in medicine

Capsaicin is used as an analgesic (a pain reliever) in topical ointments, nasal sprays, and patches to relieve chronic and neuropathic pain. Clinical trials continue to investigate the potential of capsaicin for a wide range of additional pain indications and as both an anti-cancer and anti-infective agent.

>> Special thanks to Neal Price from Chillibobs, Martin Peacock of ZimmerPeacock, Hydroveg, and The University of Reading Soft Fruit Technology Group for supporting the work of the SCI Horticulture Committee at BBC Gardeners’ World Live.

>> Our resident gardening expert, Geoff Dixon, provides plenty of gardening tips on the SCIBlog.