How do green spaces, gardens as well as fruit and vegetables impact our health and wellbeing? Professor Geoff Dixon tells us more.

‘We are what we eat’ is an aphorism that is becoming much better understood both by the general public and by healthcare professionals. Similarly, ‘we are where we live’ is gaining greater appreciation. Both these pithy observations underline the social and economic importance of horticulture and the allied art of gardening.

An exuberant display of flowers – what can be better for the soul?

Few things stimulate the human spirit more than a fine, colourful display of well grown and presented flowers. Seeing and working with green and colourful plants is increasingly recognised for its psychological power, reducing stress and increasing wellbeing. In our increasingly urbanised society, with myriads of high-rise housing blocks, the provision of well-tended parks and gardens is not a luxury – it is essential.

Hospital patients recover more quickly when they can see and sit in green spaces. Equally, providing access to gardens and gardening for schools should be a vital part of the children’s environment. They gain an understanding of biological mechanisms and the equally important need for conserving biodiversity and controlling the rate of climate change.

The recently published National Food Strategy emphasised the importance of fruit and vegetables as a major part of our diets. Both fruit and vegetables provide essential vitamins, nutrients and fibres which consumed over time diminish the incidence of cancers, coronary, strokes and digestive diseases.

Apricots are high in catechins.

Eating varying types of fruit and vegetables increases their value – apricots, for example, are high in catechins which are potent anti-inflammatory agents. Members of the brassica (cabbage) family are exceptionally valuable for mitigating diseases of ‘modern society’. All contain glucosynolates, which evolved as means for combating pest and pathogen attacks and co-incidentally provide similar services for humans. Watercress – an aquatic brassica – is rich in vitamins A, C and E, plus folate, calcium and iron. Its high water content means portions consumed fresh or as soups are low in calories.

Watercress – an aquatic brassica boasts numerous health benefits.

These messages and facts are now being recognised both publicly and politically, and not before time. For the past 50 years the universal panaceas have been pharmaceutical drugs. In moderation, these have been of immense value. Use to excess is both counterproductive and needlessly expensive health-wise and financially.

Returning to Grandma’s advice, ‘an apple a day keeps the doctor away’, supports both individual and planetary good health.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Sometimes, when you try to solve one problem, you create another. A famous example is the introduction of the cane toad into Australia from Hawaii in 1935. The toads were introduced as a means of eliminating a beetle species that ravaged sugar cane crops; but now, almost a century later, Western Australia is inundated with these venomous, eco-system-meddling creatures.

In a similar spirit, disposable face masks could help tackle one urgent problem while creating another. According to researchers at Swansea University, nanoplastics and other potentially harmful pollutants have been found in many disposable face masks, including the ones some use to ward off Covid-19.

After submerging various types of common disposable face masks in water, the scientists observed the release of high levels of pollutants including lead, antimony, copper, and plastic fibres. Worryingly, they found significant levels of pollutants from all the masks tested.

Microscope image of microfibres released from children's mask: the colourful fibres are from the cartoon patterns | Credit: Swansea University

Obviously, millions have been wearing single-use masks around the world to protect against the Covid-19 pandemic, but the release of potentially harmful substances into the natural environment and water supply could have far-reaching consequences for all of us.

‘The production of disposable plastic face masks (DPFs) in China alone has reached approximately 200 million a day in a global effort to tackle the spread of the new SARS-CoV-2 virus,’ says project lead Dr Sarper Sarp, whose team’s work has been published on Science Direct. ‘However, improper and unregulated disposal of these DPFs is a plastic pollution problem we are already facing and will only continue to intensify.

The presence of potentially toxic pollutants in some face masks could pose health and environmental risks.

‘There is a concerning amount of evidence that suggests that DPFs waste can potentially have a substantial environmental impact by releasing pollutants simply by exposing them to water. Many of the toxic pollutants found in our research have bio-accumulative properties when released into the environment and our findings show that DPFs could be one of the main sources of these environmental contaminants during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.’

The Swansea scientists say stricter regulations must be enforced during manufacturing and disposal of single-use masks, and more work must be done to understand the effect of particle leaching on public health and on the environment. Another area they believe warrants investigation is the amount of particles inhaled by those wearing these masks.

‘This is a significant concern,’ adds Sarp, ‘especially for health care professionals, key workers, and children who are required to wear masks for large proportions of the working or school day.’

Many of us have contemplated buying a reconditioned phone. It might be that bit older but it has a new screen and works as well as those in the shop-front. I’m not sure, however, that any of us have thought of investing in a reconditioned liver – but it could be coming to a body near you.

Researchers based in São Paulo’s Institute of Biosciences have been developing a technique to create and repair transplantable livers. The proof-of-concept study published in Materials Science and Engineering by the Human Genome and Stem Cell Research Centre (HUG-CELL) is based on tissue bioengineering techniques known as decellularisation and recellularisation.

The organs of some donors are sometimes damaged in traffic accidents, but these may soon be transplantable if the HUG-CELL team realises its goal.

The decellularisation and recellularisation approach involves taking an organ from a deceased donor and treating it with detergents and enzymes to remove all the cells from the tissue. What remains is the organ’s extracellular matrix, containing its original structure and shape.

This extracellular matrix is then seeded with cells from the transplant patient. The theoretical advantage of this method is that the body’s immune system won’t rile against the new organ as it already contains cells from the patient’s own body, thereby boosting the chance of long-term acceptance.

However, the problem with the decellularisation process is that it removes the very molecules that tell cells to form new blood vessels. This weakens cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix. To get around this, the researchers have introduced a stage between decellularisation and recellularisation. After decellularising rat livers, the scientists injected a solution that was rich in the proteins produced by lab-grown liver cells back into the extracellular matrix. These proteins then told the liver cells to multiply and form blood vessels.

These cells then grew for five weeks in an incubator that mimicked the conditions inside the human body. According to the researchers, the results showed significantly improved recellularisation.

“It’s comparable to transplanting a ‘reconditioned’ liver, said Mayana Zatz, HUG-CELL’s principal investigator and co-author of the article. “It won't be rejected because it uses the patient’s own cells, and there’s no need to administer immunosuppressants.”

Extracellular matrix of a decellularised liver | Image Credit: HUG-CELL/USP

Obviously, there is a yawning gap between proof of concept and the operating theatre, but the goal is to scale up the process to create human-sized livers, lungs, hearts, and skin for transplant patients.

“The plan is to produce human livers in the laboratory to scale,” said lead author Luiz Carlos de Caires-Júnior to Agência FAPESP. “This will avoid having to wait a long time for a compatible donor and reduce the risk of rejection of the transplanted organ."

This technique could also be used to repair livers given by organ donors that are considered borderline or non-transplantable. “Many organs available for transplantation can’t actually be used because the donor has died in a traffic accident,” Caires-Júnior added. “The technique can be used to repair them, depending on their status.”

Even if we are at the early stages of this approach, it bodes well for future research. And for those on the organ transplant list, a reconditioned liver would be as good as a new one – complete with their very own factory settings.

Read the paper here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0928493120337814

Every day, there are subtle signs that machine learning is making our lives easier. It could be as simple as a Netflix series recommendation or your phone camera automatically adjusting to the light – or it could be something even more profound. In the case of two recent machine-learning developments, these advances could make a tangible difference to both microscopy, cancer treatment, and our health.

The first is an artificial intelligence (AI) tool that improves the information gleaned from microscopic images. Researchers at the University of Gothenburg have used this deep machine learning to enhance the accuracy and speed of analysis.

The tool uses deep learning to extract as much information as possible from data-packed images. The neural networks retrieve exactly what a scientist wants by looking through a huge trove of images (known as training data). These networks can process tens of thousands of images an hour whereas some manual methods deliver about a hundred a month.

Machine learning can be used to follow infections in a cell.

In practice, this algorithm makes it easier for researchers to count and classify cells and focus on specific material characteristics. For example, it can be used by companies to reduce emissions by showing workers in real time whether unwanted particles have been filtered out.

“This makes it possible to quickly extract more details from microscope images without needing to create a complicated analysis with traditional methods,” says Benjamin Midtvedt, a doctoral student in physics and the main author of the study. “In addition, the results are reproducible, and customised. Specific information can be retrieved for a specific purpose."

The University of Gothenburg tool could also be used in health care applications. The researchers believe it could be used to follow infections in a cell and map cellular defense mechanisms to aid the development of new medicines and treatments.

Machine learning by colour

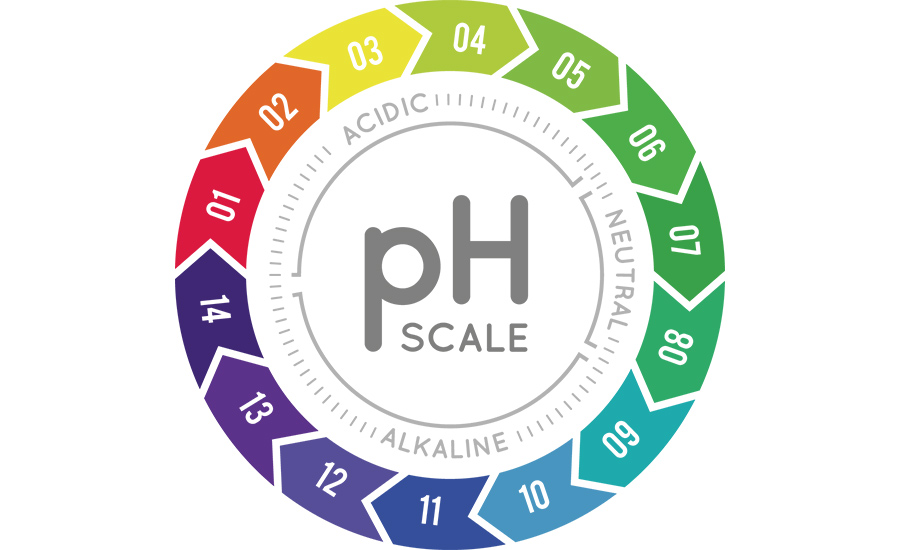

On a similar thread, machine learning has been used to detect cancer by researchers from the National University of Singapore. The researchers have used a special dye to colour cells by pH and a machine learning algorithm to detect the changes in colour caused by cancer.

The researchers explain in their APL Bioengineering study that the pH (acidity level) of a cancerous cell is not the same as that of a healthy cell. So, you can tell if a cell is cancerous if you know its pH.

With this in mind, the researchers have treated cells with a pH-sensitive dye called bromothymol blue that changes colour depending on how acidic the solution is. Once dyed, each cell exudes its unique red, green, and blue fingerprint.

By isolating a cell’s pH, researchers can detect the presence of cancer.

The authors have also trained a machine learning algorithm to map combinations of colours to assess the state of cells and detect any worrying shifts. Once a sample of the cells is taken, medical professionals can use this non-invasive method to get a clearer picture of what is going on inside the body. And all they need to do all of this is an inverted microscope and a colour camera.

“Our method allowed us to classify single cells of various human tissues, both normal and cancerous, by focusing solely on the inherent acidity levels that each cell type tends to exhibit, and using simple and inexpensive equipment,” said Chwee Teck Lim, one of the study’s authors.

“One potential application of this technique would be in liquid biopsy, where tumour cells that escaped from the primary tumour can be isolated in a minimally invasive fashion from bodily fluids.”

The encouraging sign for all of us is that these two technologies are but two dots on a broad canvas, and machine learning will enhance analysis. There are certainly troubling elements to machine learning but anything that helps hinder disease is to be welcomed.

Machine Learning-Based Approach to pH Imaging and Classification of Single Cancer Cells:

https://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/5.0031615

Quantitative Digital Microscopy with Deep Learning:

https://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/5.0034891

Rising anxiety about air pollution, physical, and mental health, exacerbated by Covid-19 and concerns about public transport, has seen an increase in the popularity of cycling around Europe, leading many cities to transform their infrastructure correspondingly.

These days, Amsterdam is synonymous with cycling culture. Images of thousands of bikes piled up in tailor-made parking facilities continue to amaze and it is routinely held up as an example of greener, cleaner, healthier cities. Because The Netherlands is so flat, people often believe it has always been this way. But, in the 1970s, Amsterdam was a gridlocked city dominated by cars. The shift to cycling primacy took work and great public pressure.

For some cities, however, the pandemic has provided an unexpected opportunity on the roads. Milan's Deputy Mayor for Urban Planning, Green Areas and Agriculture, Pierfrancesco Maran, has explained that, "We tried to build bike lanes before, but car drivers protested". Now, however, numbers have increased from 1,000 to 7,000 on the main shopping street. "Most people who are cycling used public transport before”, he said. “But now they need an alternative”.

Creating joined up cycling networks is a major challenge for urban planners.

In Paris, the Deputy Mayor David Belliard does not seem concerned that the city’s investment since the start of the pandemic will go to waste. “It's like a revolution," he said. “Some sections of this road are now completely car-free. The more you give space for bicycles, the more they will use it.” They are committed to creating a cycle culture, providing free cycling lessons and subsidising the cost of bike repairs. The city intends to create more than 650km of cycle lanes in the near future.

The success in these two cities has been supported by local government but it has also been fuelled by an understandable (and encouraged) avoidance of public transport and fewer cars on the road generally. Going forward, however, it seems likely that those last two factors won’t be present. So how do you create a cycling culture in your city in the long run?

The answer is both simple and difficult: cyclists (and pedestrians) need to have priority over cars. In Brussels, where 40km of cycle track have been put down in the last year, specific zones have been implemented where this is the case, and speed limits have been reintroduced across the city.

In Copenhagen, in the late 1970s, the Danish Cyclists’ Federation arranged demonstrations demanding more cycle tracks and a return to the first half of the century, when cyclists had dominated the roads. Eventually, public pressure paid off — although there is still high demand for more cycle lanes. A range of measures, including changes made to intersections, make cyclists feel safer and local studies show that, as cyclist numbers increase, safety also increases. In many parts of the city, it is noticeable how little of the wide roads are actually available to cars: bikes, joggers, and pedestrians are all accommodated.

Segregated cycleways, like this one in Cascais, Portugal, make people more likely to cycle.

But, if you were starting from scratch, you might not simply add cycle lanes to existing roads and encourage behavioural changes on the road. Segregated, protected bike lanes like those introduced in Paris are the next level up and the results suggest they work — separated from the roads, more people are inclined to try cycling.

Dutch experts suggest, where possible, going even further. Frans Jan van Rossem, a civil servant specialising in cycling policy in Utrecht, believes the best option is to create solitary paths, separated from the road by grass, trees, or elevated concrete. Consistency is also important. Cities need networks of cycle tracks, not just a few highways. Again, prioritising cyclists is key to the Dutch approach. Many cities have roads where cars are treated as guests, restricted by a speed limit of 30km/hour and not permitted to pass. Signage is also key.

In London, Mayor Sadiq Khan’s target is for 80% of journeys to be made by walking, cycling, and/or public transport by 2041. Since 2018, the city has been using artificial intelligence to better understand road use in the city and plan new cycle routes in the capital. However, the experience of other European capitals suggests that, "if you build it, they will come" might be a better approach than working off current usage.