The world’s top national soccer teams head to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil this summer with their coaches brimming – at least in public – with confidence. Their goal is the FIFA World Cup, an 18-carat solid gold trophy standing 36cm tall. The finalists will almost certainly be a team that combines supreme fitness, superior technical ability and superstar players able to operate as an efficient team.

The target for the world’s major chemicals industries in 2014, meanwhile, is not solid gold but firm, sustainable and profitable growth, something that has eluded many industrialised nations for the last few years. Success this year as a national chemicals industry player will also require a variety of outstanding attributes. But the most successful chemicals nations of 2014 will be almost certainly have one key factor in common: access to relatively cheap feedstocks.

The resurgence of the US chemicals industry last year and its anticipated accelerated growth in 2014 is due in no small measure to the sharp decline in natural gas prices prompted by wide-scale shale gas development.

The US and UK, whose soccer teams have been pitched into so-called ‘groups of death’, face an uphill struggle if they are to progress beyond the group stage to the knock-out rounds.

Kevin Swift, chief economist at the American Chemistry Council (ACC), is rather more sanguine about US chemical industry prospects this year than he is about the national team’s hopes of a place in the quarter finals or beyond. In its annual industry situation and outlook, the ACC sees American chemistry ‘back in the game’ following a decade of lost competitiveness.

‘Looking ahead to 2014, we anticipate a sustained global expansion that will result in growing trade,’ says Swift. ‘We also anticipate positive supply chain impacts from unconventional oil and gas developments [principally shale] in the US, through increased demand for equipment, chemicals, and services required for energy production in addition to lower fuel prices for all consumers.’

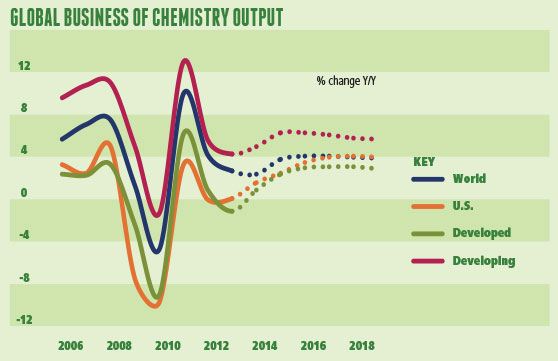

In 2013, US chemicals output by volume rose by 1.6%, according to the ACC. This year it expects production to increase by 2.5% and in 2015 it forecasts a relatively robust rise of 3.5%, with output growth hitting 4% the following year.

A revival in export markets is expected to result in strong growth this year and next for US output of plastic resins and organic chemicals. Demand from the automotive and housing sectors will help drive speciality chemicals production, while pharmaceuticals is seen as eventually emerging as a growth segment in 2015.

However, the ACC adds a yellow card note of warning: ‘Although projected year-on-year growth rates for most [US chemical] segments appear good over the next few years, they must be considered in the context of the exceptionally sharp declines seen in 2008 that continued into 2009,’ says the report.

‘Moreover, it may take years for activity to recover from these steep declines and broach past peaks,’ it adds.

The ACC’s forecasts are based on its assumption that US gross domestic product (GDP) growth will rise from 1.7% last year to 2.5% this year, accelerating to 3% in 2015.

It also believes that the global industrial cycle is beginning to turn upwards, boosted by the US, UK and other major manufacturing nations.

World GDP is expected to grow by 2.8% in 2014, and 3.2% in 2015, while global industrial production is seen rising by 4.1% in 2014 and 4.4% the following year.

In 2013, recession across most of Europe, plus a further year of depressed growth in China and other East Asian countries, led to an estimated expansion of only 2.4% in global chemicals output, according to figures compiled by the ACC. In 2014, however, the improvement in overall economic activity is expected to result in global chemicals production growth of 3.8%, rising to 4.1% in 2015.

All major chemical segments will share in the forecast growth this year, from agrochemicals with 3.1% to bulk chemicals at 3.8% and specialties at 4.2%. Next year’s growth profile by segment is very similar to 2014.

China, unsurprisingly, is forecast to be top scorer, with chemicals output expected to rise by 8.8% in 2014 and 8.5% next. India won’t be far behind, with production forecast to increase 6.7% and 8.1%, respectively. Neither of these two Asian economic tigers will be troubling the football score-keepers in Brazil this summer. But together with World Cup finalists Japan and South Korea, and soccer minnows Singapore and Taiwan, the two fastest growing Asian economies will push overall Asia-Pacific chemicals production growth to 6.5% this year and next.

By contrast, forecast chemicals output growth in Western Europe in 2014 will be relatively insipid at 1.4%, albeit a marked improvement over last year’s estimated decline of 0.1%. In 2015, production is expected to rise by 1.8%.

Germany, still the economic powerhouse of the European Union as well as a shrewd bet as World Cup semi-finalists or even better, is expected to enjoy chemicals output growth in 2014 of 1.6%, just over double the rate it achieved in 2013. Next year, however, growth is forecast to ease to 1.4%. France, which has avoided a World Cup ‘group of death’, is expected to recover from a 0.2% contraction in chemicals output in 2013 to 1.3% and 1.8% growth in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

The UK, which has serial soccer under-achiever England as its sole World Cup competitor, is expected to record chemicals output growth of 1% in 2014 and 1.6% in 2015. Although unimpressive when set against forecast US growth, it does represent a major turnaround, compared with last year’s estimated contraction of 3.2%.

The UK’s chemicals and pharmaceuticals industry certainly ended 2013 in a generally more optimistic mood. Nearly 90% of businesses in the Chemical Industries Association (CIA) said they expected sales this year to increase or stay the same as in 2013. Some 75% said they expected to maintain or expand their workforce, while 95% will increase or hold their current research and development investment. And 80% expect to increase capital expenditure or peg it at current levels.

The survey was, however, conducted ahead of UK Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne’s autumn statement in which he had been urged by CIA chief executive Steve Elliott to take urgent action on UK energy costs. Elliott had warned that, without prompt measures to reduce the burden of high energy costs and excessively restrictive European Union regulations, the generally optimistic outlook of CIA members would fade.

Although Osborne’s statement included widely-predicted tax incentives aimed at stimulating investment in shale gas exploration and production, it clearly confounded the CIA’s hopes of government intervention to reduce industrial energy costs.

‘We need to see more action to ensure affordable and secure energy supplies,’ responded Elliott. ‘In particular, we need to see the promised rebates from the range of climate policies impacting on our power prices made broader and deeper in a way that provides better long-term business certainty for investment.’

His concerns were later echoed by Jim Ratcliffe, chairman and founder of global petrochemicals giant Ineos. Ratcliffe, who last year briefly closed Ineos’s huge Grangemouth, Scotland, chemicals complex in a showdown with the plant’s trade unions, complained that high UK energy costs continued to undermine global competitiveness. In an interview broadcast on BBC radio just before Christmas, Ratcliffe said the UK had the most expensive industrial energy in the world: ‘More expensive than Germany, more expensive than France and much more expensive than the US.’

Ratcliffe, whose brinkmanship in threatening the permanent closure of Grangemouth resulted in an almost complete cave-in by the plant’s trade union leaders, sees cheaper shale gas imported from the US in the medium term and perhaps supplied from UK reserves in the long term as essential to Ineos’s future in Britain.

He also took the opportunity of criticising the deal under which developers of the new nuclear power plant at Hinkley in Somerset will receive a UK government guaranteed price of £92.50 per megawatt hour (MW h) for the electricity it generates. Ratcliffe said Ineos recently agreed a deal for nuclear power in France at €45 (about £38) per MW h and dismissed out of hand the prospect of new UK atomic power being even remotely competitive for the chemicals industry at Hinkley C price levels.

Ineos is the world’s fourth largest chemicals company. It has large production facilities in the US, France, Germany and Italy as well as the UK, putting it in a good position to make cross-border and cross-continent comparisons on energy costs and overall competitiveness.

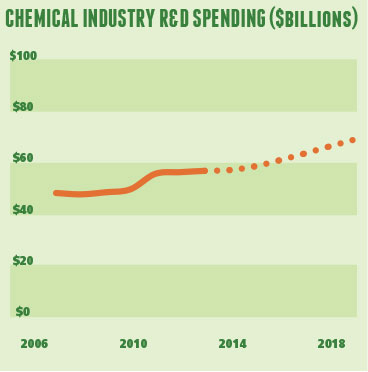

The huge energy cost base transformation wrought in the US by the widespread development of shale gas has prompted much needed fresh investment in new chemicals infrastructure. In 2013, capital spending on US chemicals plant rose by 10% to an estimated $42.4bn, following a near 17% leap in 2012 to $38.5bn. This year, capital expenditure is forecast to rise by another 9%, to $45.2bn, with a similar percentage jump in 2015, to $50.3bn.

Global capital spending rose 6.0% last year to an estimated $438.8bn and is forecast to rise by 6.6% this year, to $467.7bn. Investment is expected to rise even faster in 2015, by 7.8% to $504.3bn. The recovery in world economic growth and consequent improvement in chemicals industry prospects helped maintain global capacity utilisation in 2013 at an estimated 85.9%. This year it is forecast to improve to 86.2%, rising to 86.5% in 2015.

Capacity utilisation in the US is also seen as stable. It was virtually unchanged in 2013, year-on-year, at 75.2% and is expected to average 75.3% this year and 75.4% in 2015.

Prospects for employment in the chemicals industry are certainly better at the end of 2013 than they were in December 2012. But there are few signs of any major short-term fillip for jobs, with overall employment in the established industrial Western nations looking flat this year, although growth prospects remain more buoyant in Asia and the Middle East.

Most of the world’s chemical companies will look back on 2013 as a tough journey in which the global economic slowdown offered only limited opportunities for anything like unbridled optimism for the future.

Yet there were reasons to be cheerful, for some, particularly in the third quarter. Overall, the global chemicals industry fared rather better than it feared last year, thanks to a swifter and more robust than expected recovery in the global economy.

The cloak of economic recession, however, still covers many areas of Europe, with only a few major industrialised countries delivering both growth and realistic prospects of that growth continuing through 2014.

Chemical companies have taken some comfort from relative stability in money supply and general inflation but few are willing to bet that this stability can be guaranteed beyond any cutback by central banks in quantitative easing.

There are also the almost perennial fears of localised hostilities in the Middle East degenerating into regional conflict, while China and Japan’s sabre-rattling over the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in the energy rich East China Sea is adding substantially to global political tension.

Generally, though, the outlook is significantly more optimistic than this time last year although there are still a considerable number of downside risks.

Brazil, Germany, Italy, Spain and Argentina, in particular, harbour genuine hopes of their national teams lifting the World Cup in Rio de Janeiro this summer.

For most other teams, success will be measured on a more modest scale. The success yardstick for the chemicals industry will be of limited dimensions this year. Stability, plus modest and sustainable growth is scarcely the stuff of dreams. But it is now beginning to look like a realistic proposition beyond the Asia Pacific and Middle East.

Neil Sinclair is a freelance journalist based in London