The UK government has indicated its willingness to look at all possible energy options to end dependency on Russian gas and cope with spiralling prices. So could we bring back fracking as part of the solution? Maria Burke reports

The process of fracking, short for hydraulic fracturing, is widely used in the US. Here in the UK, supporters believe it would bring down gas prices by putting more gas on the market; reduce reliance on imports and coal production; provide more jobs in rural areas where deposits are mainly found; and reduce water use compared with coal extraction.

But there appears to be little public appetite. In autumn 2021, a survey commissioned for the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy found only 17% of the UK public were in favour.1

Fracking opponents argue that it triggers earthquakes; uses chemicals that could contaminate local water supplies or cause pollution; requires significant amounts of water; and produces fossil fuels that emit greenhouse gases. Rural areas would become industrialised, they say, and wildlife and natural habitats would be put at risk, while investment in fracking diverts money away from renewable energies.

Many environmental campaign groups are convinced that fracking is bad for the climate and risks causing pollution. An analysis for chemicals charity CHEM Trust in 2015 found that chemicals from fracking sites have the potential to cause significant contamination, which could damage sensitive ecosystems, including killing wildlife, as, it claims, has happened in the US.2

However, Quentin Fisher, Professor of Petroleum Geoengineering at the University of Leeds, says impacts on the local environment from fracking should be minimal. ‘Some are worried about groundwater contamination, but this is a complete myth. There could be minor seismicity but despite over 2m frack jobs being completed around the world there have been no injuries or significant damage to housing caused by these low magnitude events. For those living around sites there will be an increase in traffic while constructing the well pad and drilling the wells, after which the site can be returned to the way that it was found with a small well head. Potentially the biggest impact is the influx of protesters, which tend to cause disruption and mess.’

‘Fracking can cause earthquakes – but not big ones,’ agrees Richard Davies, a petroleum geologist at Newcastle University. ‘Before fracking in the UK, between 1970 and 2012 at least, around 21% of UK earthquakes bigger than 1.5 in scale were man-made.’ However, he says shale gas exploitation could cause pollution, such as methane entering the atmosphere.

The UK is in the midst of an energy crisis with ever increasing prices driving people into fuel poverty whilst giving huge sums of money to oppressive regimes. It’s a ridiculous situation with so much gas under our feet and we are offering to drill a shale test site to show that a competent operator can be trusted to develop the technology safely.

Sir Jim Ratcliffe INEOS chairman.

UK fracking

Four areas in the UK have been identified as potentially viable for the commercial extraction of shale gas: the Bowland-Hodder area in Northwest England, the Midland Valley in Scotland, the Weald Basin in Southern England, and the Wessex area in Southern England, according to the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the London School of Economics. But it’s not clear how much shale gas there is.

In 2020, Warwick Business School reviewed forecasts from the industry organisation UK Onshore Oil and Gas to calculate that UK fracking might produce between 90bn and 330bn m3 of natural gas between 2020 and 2050.3 Using future demand figures from National Grid, they calculated that this represented 17-22% of projected UK consumption over that period. However, the review stressed the high levels of uncertainty around these numbers, pointing out there are no estimates of ‘proven reserves’ on which to base commercial development.

The problem is that it’s very difficult to accurately estimate reserves without drilling and hydraulically fracturing several wells. ‘Nobody knows how much gas could be extracted,’ says Davies. ‘Even the operators don’t know. Anyone who claims to know is guessing. We may need tens, perhaps hundreds of wells to reduce uncertainty.’ Previous fracking operations had to stop when they produced tremors above the UK regulatory limit of 0.5 on the Richter scale, which meant interrupting production tests to gauge gas flow.

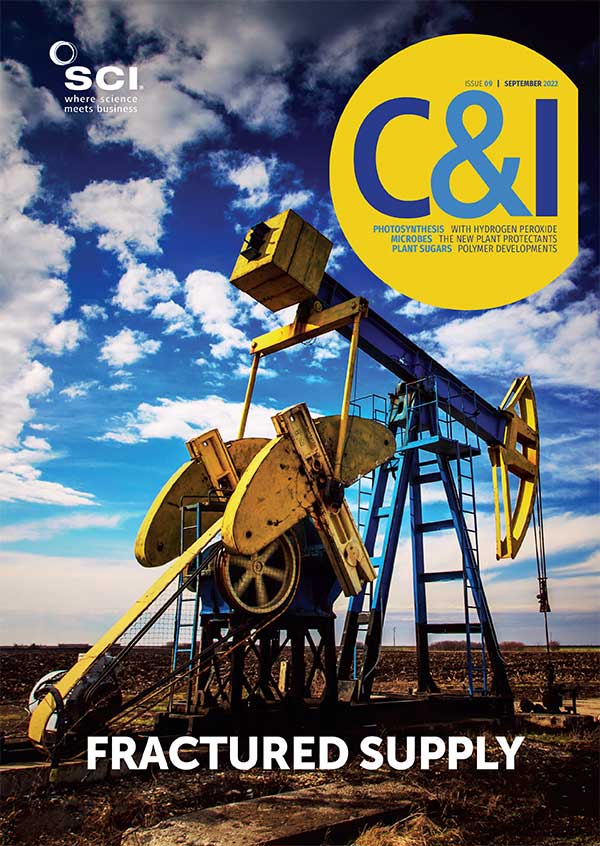

The only fracking wells in UK shale rock are in Lancashire, operated by Cuadrilla Resources. They were drilled to vertical depths of approximately 2.25km and onwards horizontally for a further 0.75km each through the shale. Cuadrilla says it has confirmed the presence of high-quality natural gas before operations had to stop under the moratorium in 2019 after an earthquake was recorded (https://cuadrillaresources.uk/uk-regulator-withdraws-notice-to-plug-shale-gas-wells-at-preston-new-road-pnr-lancashire-site/) at it’s site on Preston New Road, Lancashire. Operations had restarted in 2017 after a six-year ban on fracking ended; the ban was initially established after two earlier earth tremors were recorded at the Preston New Road site in 2011.

1.5

Between 1970 and 2012 – before fracking in the UK – around 21% of UK earthquakes bigger than 1.5 in scale were man-made.

90bn

In 2020, Warwick Business School reviewed forecasts from UK Onshore Oil and Gas to calculate that UK fracking might produce between 90bn-330bn m3 of natural gas from 2020-2050. Using future demand figures from National Grid, they calculated that this represented 17-22% of projected UK consumption over that period.

2.25km

The only fracking wells in UK shale rock are in Lancashire, operated by Cuadrilla Resources. They were drilled to vertical depths of approximately 2.25km and onwards horizontally for a further 0.75km each through the shale.

The Scottish Parliament has an indefinite moratorium on fracking, first introduced in 2015, and the Welsh government is not considering applications from developers.

But things started to change in England when, in March 2022, the oil and gas regulator – now called the North Sea Transition Authority – withdrew its order to plug and abandon Cuadrilla’s two wells at Preston New Road by the end of June 2022. The company is now allowed to ‘temporarily plug’ the wells until the end of June 2023 and has a year to publish ‘credible’ plans to re-use the wells.

Then, in April 2022, the government commissioned the British Geological Survey (BGS) to conduct a new study to examine safety concerns around fracking. The UK Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng said it was right to explore all possible domestic energy sources. The Conservative Party 2019 manifesto promised not to support shale gas extraction ‘unless the science shows categorically that it can be done safely’.

The BGS was given three months to investigate new developments in the science of fracking, particularly whether there are new techniques which could reduce the risk and magnitude of seismic events; and if there are, whether they would be suitable for use in in the UK. It will also consider how the seismicity caused by fracturing compares to other forms of underground energy production, such as coal mining; ‘safe’ thresholds for activity; advances in modelling of shale; and whether there are other sites, outside of Lancashire, with a lower risk of seismic activity.

Cuadrilla’s Preston New Road Exploration Site

Image credit: Cuadrilla

Responding to the April 2022 announcement, Francis Egan, CEO of Cuadrilla Resources, said: ‘This review may be a tentative first step towards overturning the moratorium. Anyone who has been following the science since 2019 will be surprised if the government in fact needs three months to take stock of the clear evidence that already exists.’ Egan pointed out that the Oil and Gas Authority’s report in 2020 found that seismicity at the first of Cuadrilla’s two Preston New Road wells was ‘imperceptible’.4 He also pointed to a 2012 Royal Society report which said that ‘seismic risks are low’ and are less noticeable than the hundreds of naturally occurring seismic events which happened in the UK every year.5

Also in April, Ineos, one of the world’s largest chemicals and energy companies, wrote to the UK Government offering to develop a fully functioning shale test site to demonstrate the safety of fracking. ‘The UK is in the midst of an energy crisis with ever increasing prices driving people into fuel poverty whilst giving huge sums of money to oppressive regimes,’ said Sir Jim Ratcliffe, INEOS chairman. ‘It’s a ridiculous situation with so much gas under our feet and we are offering to drill a shale test site to show that a competent operator can be trusted to develop the technology safely.’

However, in early June 2022, ministers rejected an appeal from Ineos, which was seeking to overturn a Rotherham Council decision to refuse planning permission for a shale gas exploration site in Woodsetts. Ineos was given six weeks to challenge the decision in the High Court. Ministers refused planning permission citing reasons such as damage to the green belt, as well as adverse visual impacts and harm to properties from a 3m-high acoustic barrier that was due to be built around the site.

17%

Only 17% of the UK public were in favour of fracking, according to a 2021 survey for UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

Fracking future?

Some scientists argue that while fracking is viable in the UK, it would never be as successful industry as in the US. ‘[Fracking]’s feasible, but not proven after a decade of trying,’ says Davies. ‘It’s completely unrealistic for politicians to think this will make a big dent in the costs of gas or our reliance on imports.’

There are many reasons why experts believe shale gas won’t alleviate the UK’s energy supply crisis. ‘Much has been made of the amount of gas trapped deep underground within the UK’s shale formations and sure enough if you dig up a piece of the appropriate shale and heat it in an oven, methane will be released,’ says Jon Gluyas, Director of the Durham Energy Institute at Durham University. ‘The resource is indeed huge but the reserve – that which can be won by drilling and fracking is tiny – and indeed, to date, the proven commercial reserve for the UK is zero.’

One of the problems is that the UK has the wrong kind of shale, he says. The best type is brittle and rich in silica but most UK shale is rich in malleable clays that won’t hold a fracture well. ‘We also have the wrong kind of geology: small geological basins rather than vast tracts of identical geology and our island is too crowded to get in the thousands of wells to sustain a shale gas industry. Even if shale gas could be won, the time to delivery of first gas would be measured in a handful of years at best, not the weeks and months to solve the immediate energy crisis.’

Stuart Haszeldine of the School of GeoSciences at the University of Edinburgh agrees: ‘The UK has not discovered any good shale for onshore gas production. There isn’t much gas. The most important new evidence to emerge since Cuadrilla gave up on its Lancashire boreholes has been to analyse gas production from real rock samples. This shows that the measured gas in place is very small – 15 times less than the original theoretical estimates.’6

In addition, he says, the gas is hard to extract; the total gas produced by Cuadrilla from Lancashire could be enough to provide heating and water to 508 three-bed semi-detached houses for 18 days. Plus, the risk of earthquakes is real. ‘Residents living around the drill sites noticed earthquakes under their houses and didn’t like it. Another eight years of work showed that more expensive and complicated boreholes could be drilled – and still caused earthquakes of increasing energy, which cannot be predicted accurately.’

Another issue is that the UK has no drillers or drill rigs. ‘To have any impact at all on gas production, the UK would need to drill many hundreds of shale boreholes every year for the next 10 years. Complicated drilling equipment is needed, with very specialist equipment to engineer super-high pressures underground, with highly skilled crews. The UK no longer has this special kit or skills.’

What is fracking?

Fracking is a drilling technology used for extracting oil, natural gas, geothermal energy, or water from deep underground. In the UK, the focus is on extracting previously inaccessible deposits of natural gases trapped inside layers of rock. Shale formations are especially likely to contain vast amounts of natural gases, but shale is found deep below ground and is relatively impermeable.

Fracking involves drilling a well into the ground often to a depth of over 1500m. Fracking fluid – a high-pressure mixture of water, sand, and chemicals – is injected into the well at extremely high pressure. This breaks the rock apart and creates cracks that allow the natural gases to move into the well and eventually flow up to the surface.

References

1 BEIS PAT Autumn 2021 Energy Infrastructure and Energy Sources.

2 Fracking pollution: how toxic chemicals from fracking could affect wildlife and people in the UK and the EU.

3 Briefing: Shale gas and energy security, March 2020.

4 Interim report of the scientific analysis of data gathered from Cuadrilla’s operations at Preston New Road.

5 Final report – Shale gas extraction, Royal Society

6 Nature Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11653-4