BY RENA HALPENNY

SCI’s economist Rena Halpenny looks at the international race for life sciences companies – and which countries are winning.

Life sciences firms are a critical asset for any major economy; the pharmaceutical industry has contributed over $2tn to world GDP and accounted for 75m jobs globally in 2022, both directly and through wider spillover effects.

These are businesses that create good jobs, support a wider ecosystem of suppliers and can be a key indicator of the industrial momentum of a particular economy. As such, countries of all sizes are looking to attract – and retain – life science companies to boost their economies and to support broader objectives like building national resilience.

The benefits of a thriving life science industry are widely recognised, and the global race to attract life science companies has gained new momentum as global supply chains come under pressure. The US, in particular, is becoming increasingly explicit about its desire to have pharma businesses moving more of their operations there. That’s in part because, while North America is certainly the biggest market for pharmaceuticals sales – accounting for 55% of all sales – only about 10% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients by volume for the finished drug products used in the US are actually made there.

Pharma manufacturing and R&D are extremely global. So, according to the data, who are countries leading the race and how have they done it?

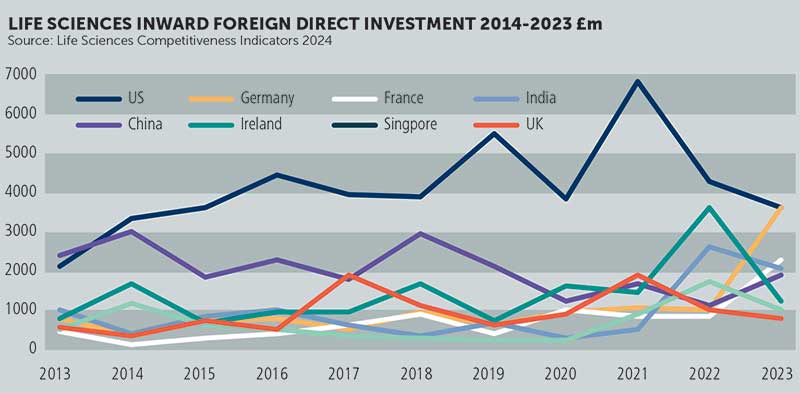

Germany, Switzerland, the US and Ireland are among the biggest exporters of pharmaceuticals (and the US is the biggest importer). The US, Germany, France, India, China and Ireland were the top six recipients of foreign direct greenfield investment in life sciences in 2023.

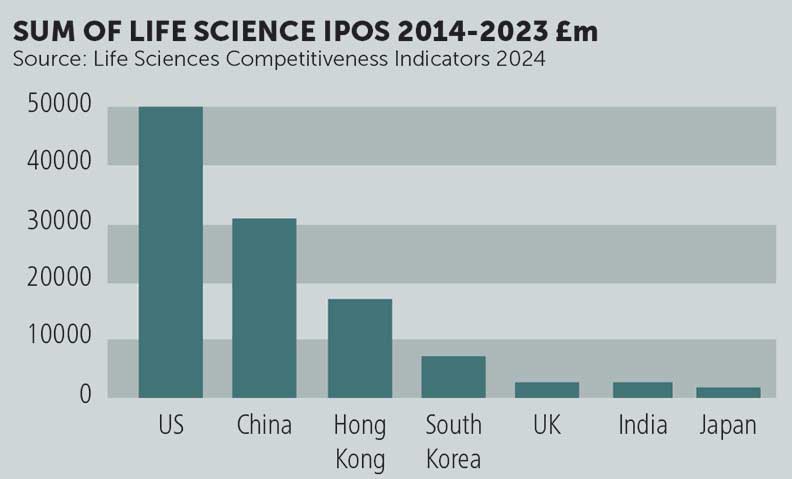

Globally, the US, China and Hong Kong saw substantial life science IPO activity between 2014 and 2023. For example, while the US economy is around seven times the size of the UK, the US raised nearly 18 times more than the UK in life science IPOs between 2014 and 2023, China raised nearly 11 times more than the UK while Hong Kong, which has an economy around a tenth the size of the UK, raised six times more. Meanwhile, pharma R&D investment in China is now outpacing both the US and Europe by a significant margin, according to data from the European Federation of Pharmaceuticals Industries and Associations.

And it’s clear that, for some countries, the life sciences industry is playing an outsized role in their economy. For a country like Switzerland, its pharma strength has for a long time been a key contributor to its growth: pharmaceutical exports in Switzerland account for around 30% of total exports and the value of all exports of goods and services is equivalent to just over 70% of Swiss GDP. Switzerland is home to two of the top global pharmaceutical companies: Roche and Novartis. The UK is also home to two top pharma companies, AstraZeneca and GSK, but the growth contribution of pharma to the UK economy is currently much less.

There is clear evidence that a thriving life sciences sector can reap dividends for an economy – and changing the path of an economy to better support life sciences is entirely possible.

For example, over the last 25 years, Ireland has created an investment-friendly economic environment, which has resulted in pharmaceuticals providing a big part of the country’s growth momentum.

In 2024, Irish exports of medicinal products and pharmaceuticals accounted for over 40% of all merchandise exports, rising from around 6% in 2000, outstripping other countries.

Low rates of corporate tax, plus generous R&D tax credits, tax relief on the acquisition of IP and more have all helped support this development in Ireland.

We can see from the graphs the significance of exports in Ireland’s economy and particularly pharmaceutical exports in that its growth trend mirrors the path for total merchandise exports.

Comparing the economic growth rates of both countries also highlights how influential the life science sector has been in supporting the Irish economy. In the last two decades, Ireland’s GDP growth has averaged over 5% reflecting the positive influence of life sciences in the Irish economy.

Pharmaceuticals have so far largely avoided being targeted with tariffs by US (although this may soon change) indeed, it’s partly the ability for countries to drive economic growth by providing a base for pharma companies, which has attracted the displeasure of the US Administration.

The US interest in tariffs reflects the fact that, despite the US being a major player in the pharmaceutical industry, it is running a large pharmaceutical trade deficit, while competitors, including Ireland, Switzerland and Germany, have been recording huge pharmaceutical trade surpluses.

North America accounted for over 50% of all global pharmaceutical sales in 2022, although this reflects the scale of this economic area. The European countries (including the UK) accounted for around 22% of global sales, China 8.1% and Japan 4.9%.

Many countries want to boost the prospects of their local life science companies and attract more investment from overseas while also preventing the leakage of innovation wealth.

The UK is the latest country to set out how it plans to do this, but it by no means alone; the US CHIPS and Science Act – as well as the more recent enthusiasm for tariffs in the White House – is another example. In July 2025, the European Union unveiled its own strategy aimed at making the EU the most attractive place for life sciences businesses by 2030, backed with over €10bn from EU funding programmes. And, after a few years of disruption, green shoots are emerging in terms of investment in China’s life sciences sector, according to consultant, LEK, with funding from the Natural Science Foundation of China returning to growth last year. China is also becoming an increasingly important source of R&D for companies seeking to license-in antibody-drug conjugates and other novel oncology treatments, according to research from consultant EY earlier in 2025.

The UK’s recently published Modern Industrial Strategy policy paper seeks to create the conditions under which by 2030, the UK can become the leading life sciences economy in Europe, and by 2035, the third most important life sciences economy behind the US and China. In its favour, the UK has four of the top ten universities for life sciences and medicine and ranks third after the US and China in terms of global medical sciences academic citations.

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

But, as the world moves away from globalisation to a new trading order it remains to be seen who will win out in the battle to attract and retain pharmaceutical investment.