By rethinking the way our products are designed and changing the way we use plastics, we can tackle the blight of marine litter and the general accumulation of plastic waste. But, as Professor Richard Thompson said in our latest SCItalk, systemic issues and historical excesses have made this no easy task.

Contrary to popular perception, plastic is not the villain. When it comes to marine littering, we are the ogres, with our single-use bottles bobbing in the oceans and the detritus of our everyday lives littering the coastline.

We are the reason why 700 species are known to encounter plastic debris in the environment. It is because of us that plastics have beaten us to the bottom of the deepest oceans and glint in the sun near the summit of Mt. Everest.

According to Richard Thompson, of the Marine Institute School of Biological and Marine Sciences at the University of Plymouth: ‘Plastic debris is everywhere. Its quantity in the ocean is likely to triple between 2015 and 2025.’

As Professor Thompson pointed out all of these facts to his audience in our latest SCItalk on 23 March, he outlined potential solutions. However, there is no ignoring the depth of the issues at hand when it comes to the litter in our seas.

The problems

1 - The weight of history

Society has gradually woken up to the menace of discarded plastics and, laterally, to the threat of microplastics and nanoplastics. The problem is that we left the barn door open decades ago. So, all of those plastic microbeads from shower gels, fibres from clothing, and tyre wear particles polluted our seas for many years before it came to public and scientific attention.

Professor Thompson said that 300 papers were published globally on microplastics in the last academic year alone, but research in the area was relatively thin on the ground before Thompson and his colleagues released their pioneering study on microplastics in Science in 2004.

2 - Bad habits

‘The business model for the use of plastics hasn’t really changed since the 1950s,’ Professor Thompson said. According to him, we have had 60 years of behavioural training to just throw products away, and our waterways reflect this attitude.

According to Professor Thompson, 50% of shoreline litter items recorded during the 2010s originated from single-use applications. Without a sea change in our attitude towards single-use items, this problem will persist.

>> Why are we ignoring climate change and what can we do about it? Read more on our blog post.

Microplastics have been subject to great scrutiny, but much of the research is quite recent.

3 - We need to talk about nanoplastics

The problems with larger plastics and even microplastics are now well documented. The worrying thing, according to Thompson, is that there are knowledge gaps when it comes to nanoplastics in the natural environment. What are the effects of nanoplastic ingestion? What are the effects of human health? Time will tell, but Thompson was keen to ask if we really need that information before we take action.

He was more sanguine about the effects of microplastics. ‘The concentration of microplastics is probably not yet causing widespread ecological harm,’ he said, ‘but if we don’t take measures, we’ll pass into widespread ecological harm within the next 50-100 years.’

The solutions

It seems counterintuitive to think of petrochemical plastics as a sustainable solution; and yet, despite the environmental problems posed by their durability, they do have a role to play in a greener approach.

‘If used responsibly, plastics can reduce our footprint on the planet,’ Thompson noted. Indeed, the lightweight plastic parts in our cars and in aviation can actually help reduce carbon emissions. But despite their merits, how do we keep plastic litter from our seas?

1 - Design for end of life… and a new one

To illustrate a flaw in the way we design plastic products, Professor Thompson gave the example of an orange coloured drinks bottle. While the bright colour may help sell juice drinks, there is an issue with recycling these coloured plastics because their value as a recyclate is lower. Clear plastics, on the other hand, are much more viable to recycle.

He argues that many products aren’t being designed with the whole lifecycle in mind. ‘We’re still failing to get to grips with linking design to end of life,’ he said, before highlighting the importance of communicating how products should be disposed of right from the design stage.

Basically, our products should be designed with end of life in mind. ‘If we haven’t even designed a plastic bottle properly,’ he lamented, ‘what hope do we have with something that’s more complicated?’

Those brightly coloured plastic bottles look nice and fancy, but they can be challenging to recycle in a circular economy.

2 - Ever recycle? Ever fail? Recycle again. Recycle better

Professor Thompson argued that better practices are needed to help divert materials away from our seas (and it should be noted that there are other types of discarded materials to be found there). If we recycle greater quantities of end of life plastic products and bring them into a circular economy, he said, ‘we’d decouple ourselves from oil and gas as the carbon source for new production because the carbon source we use would be the plastic waste’.

He said more could also be done with labelling so that customers know whether, for example, a product is compostable and which waste stream it needs to be placed in to achieve that. He also noted that addressing our single-use culture would be a good place to start if we want to change the business model of linear use.

3 - Broaden the discussion and pull those policy levers

The good news is that there is an appetite for change. ‘Ten years or so ago there was no consensus that there was a problem,’ Thompson noted. ‘I would argue that this has changed.’ However, he also feels that it is essential to gather reliable, independent evidence to inform interventions, rather than espousing solutions that could make things worse.

‘We need to gather that evidence from different disciplines,’ he said. ‘We need to have at the table product designers and couple them with the waste managers. We need to have economists at the table. We also need to bring in social scientists to look at behaviour. We’ve got to think about this in the round.’

He also felt that policy measures – such as mandating recycled content – could be a good option, along with better design and disposal.

The tools we need to tackle plastic pollution are already at our disposal. We just need to act more responsibly – which, unfortunately, has been part of the problem all along.

As Professor Thompson said: ‘It’s not the plastics per se that are the problem – it’s the way we’ve chosen to use them.’

>> For more interesting SCI talks like Professor Thompson’s, check out our YouTube channel.

>> Find out more about the work of Professor Thompson and his colleagues here: https://www.plymouth.ac.uk/research/marine-litter.

The War on Plastic is a grand title. To most of us, it doesn’t seem like much of a war at all – more like a series of skirmishes. Nevertheless, if you look closely, you’ll see that a lot of companies are tackling the issue.

GSK Consumer Healthcare (GSKCH) is one such organisation. The healthcare brand that gave us Sensodyne and Advil has launched a carbon neutral toothbrush to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels (which create virgin plastic).

The composition of its Dr. Best tooth scrubber is interesting. The handle comprises a mixture of a cellulose derived from pine, spruce, and birch trees and tall oil, which comes from the wood pulping industry. The bristles are made from castor oil and the plastic-free packaging includes a cellulose window.

According to GSKCH, Dr. Best is Germany’s favourite toothbrush brand and there are plans to apply the technology to toothbrushes across its portfolio, including its Sensodyne brand. At the moment, GSK needs to apply carbon offsetting initiatives to make the toothbrush carbon neutral, but it says it is working on future solutions that do not require this approach.

Net zero shopping

GSK isn’t the only company that is actively reducing the use of plastics and minimising waste. Supermarket chain Morrisons has made aggressive moves in recent years to cut waste, and has just launched six ‘net zero waste’ stores in Edinburgh that will operate with zero waste by 2025.

Customers at these stores will be able to bring back hard-to-recycle plastics such as food wrappers, foils, yoghurt tubs, mixed material crisp tubes, coffee tubs, batteries, and plant pots. At the same time, all store waste will be collected by a range of specialist waste partners for recycling within the UK, and unsold food will be offered to customers at a cheaper price on the Too Good to Go app.

Morrisons’ proactive approach will help find a new life for hard-to-recycle packaging.

‘We’re not going to reach our ambitious targets through incremental improvements alone,’ said Jamie Winter, Sustainability Procurement Director at Morrisons. ‘Sometimes you need to take giant steps and we believe that waste is one of those areas. We believe that we can, at a stroke, enable these trial stores to move from recycling around 27% of their general waste to over 84% and with a clear line of sight to 100%.

‘We all need to see waste as a resource to be repurposed and reused. The technology, creativity and will exists – it’s a question of harnessing the right process for the right type of waste and executing it well.’

If this approach is successful, Morrisons plans to roll out the zero waste store format in all of its 498 stores across the UK next year.

>> Interested in reading more about sustainability and the environment? Check out our blog archive.

Stamping out single-use plastics

The government has also issued its latest battle cry in the war on plastics. Having defeated plastic straws, stirrers and cotton buds, it has turned its attention to other single-use plastics.

Single-use plastic plates, cutlery and polystyrene cups are among the items that could be banned in England following public consultation.

The humble cotton bud has now been retired from active service.

Somewhat surprisingly, it estimates that each person in England uses 18 single-use plastic plates and 37 single-use plastic items of cutlery each year; so, it has begun moves to cut out this waste stream.

Environment Secretary George Eustice said: “We have made progress to turn the tide on plastic, banning the supply of plastic straws, stirrers and cotton buds, while our carrier bag charge has cut sales by 95% in the main supermarkets. Now we are looking to go a step further as we build back greener.”

All in all, it’s encouraging to see that companies and the government are brushing up on their sustainable practices.

>> Curious to find out what the future looks like for lab-processed food and meat alternatives? Read what the experts say here.

Every tin can dropped into our recycling bins is a small act of faith. We hope each one is recycled, yet the figures take some of that fervour from our faith. According to UK government statistics from 2015-2018, only about 45% of our household waste is recycled. Similarly, the UN has noted that only 20% of the 50 million tonnes of electronics waste produced globally each year is formally recycled. So, it’s fair to say we could do better.

Thankfully, thousands of people around the globe are working on these problems and two recent developments give us grounds for optimism. The first involves upcycling metal waste into multi-purpose aerogels, and the second involves fully recyclable printed electronics that include a wood-derived ink.

Upcycling metal waste

Researchers at the National University of Singapore (NUS) claim to have turned one person’s trash into treasure with a low-energy way to convert aluminium and magnesium waste into high value aerogels for the construction industry.

To do this, they ground the metal waste into a powder and mixed it with chemical cross-linkers. They heated this mixture in an oven before freeze-drying it and turning it into an aerogel. The team says this simple process makes their aerogels 50% cheaper than commercially available silica aerogels.

Aerogels have many useful properties. They are absorbent, extremely light (hence the frozen smoke nickname), and have impressive thermal and sound insulation capabilities. This makes them useful as thermal insulation materials in buildings, in piping systems, or for cleaning up oil spills. However, the NUS team has loftier goals than that.

There is a great need for less energy intensive ways to recycle metals

“Our aluminium aerogel is 30 times lighter and insulates heat 21 times better than conventional concrete,” research team leader Associate Professor Duong Hai-Minh whose research has been published in the Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management. “When optical fibres are added during the mixing stage, we can create translucent aluminium aerogels which, as building materials, can improve natural lighting, reduce energy consumption for lighting and illuminate dark or windowless areas. Translucent concrete can also be used to construct sidewalks and speed bumps that light up at night to improve safety for pedestrians and road traffic.”

The aerogels could even be used for cell cultivation. Professor Duong explains: “Microcarriers are micro-size beads for cells to anchor and grow. Our first trials were performed on stem cells, using a cell line commonly used for testing of drugs as well as cosmetics, and the results are very encouraging.”

Whatever about these speculative applications, this upcycling method will hopefully help us find new homes for all types of metal waste including metal chips and discarded electronics.

Recyclable printed electronics

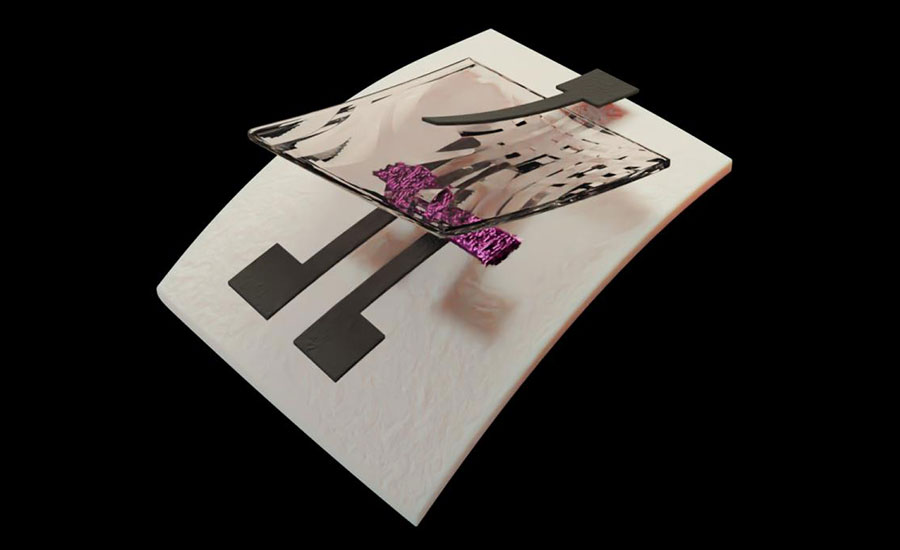

A team at Duke University has also made interesting progress in reducing electronic waste. The researchers claim to have developed fully recyclable printed electronics that could be used and reused in a wide range of sensors.

The researchers’ transistor is made from three carbon-based inks that can be printed onto paper, and their use of a wood-derived insulating dielectric ink called nanocellulose helps make them recyclable. Carbon nanotubes and graphene inks are also used for the semiconductors and conductors, respectively.

A 3D rendering of the first fully recyclable, printed transistor. CREDIT: Duke University

“Nanocellulose is biodegradable and has been used in applications like packaging for years,” said Aaron Franklin, the Addy Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Duke, whose research has been published in Nature Electronics. “And while people have long known about its potential applications as an insulator in electronics, nobody has figured out how to use it in a printable ink before. That’s one of the keys to making these fully recyclable devices functional.”

The team has developed a way to suspend these nanocellulose crystals (extracted from wood fibres) with a sprinkling of table salt to create an ink that performs well in its printed transistors. At the end of their working life, these devices can be submerged in baths with gently vibrating sound waves to recover the carbon nanotubes and graphene components. These materials can be reused and the nanocellulose can be recycled just like ordinary paper.

The team conceded that these devices won’t ruffle the trillion dollar silicon-based computer component market, but they do think these devices could be useful in simple environmental sensors to monitor building energy use or in biosensing patches to track medical conditions.

Read about the Duke University research here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41928-021-00574-0

Take a look at the NUS study here: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10163-020-01169-1