How do green spaces, gardens as well as fruit and vegetables impact our health and wellbeing? Professor Geoff Dixon tells us more.

‘We are what we eat’ is an aphorism that is becoming much better understood both by the general public and by healthcare professionals. Similarly, ‘we are where we live’ is gaining greater appreciation. Both these pithy observations underline the social and economic importance of horticulture and the allied art of gardening.

An exuberant display of flowers – what can be better for the soul?

Few things stimulate the human spirit more than a fine, colourful display of well grown and presented flowers. Seeing and working with green and colourful plants is increasingly recognised for its psychological power, reducing stress and increasing wellbeing. In our increasingly urbanised society, with myriads of high-rise housing blocks, the provision of well-tended parks and gardens is not a luxury – it is essential.

Hospital patients recover more quickly when they can see and sit in green spaces. Equally, providing access to gardens and gardening for schools should be a vital part of the children’s environment. They gain an understanding of biological mechanisms and the equally important need for conserving biodiversity and controlling the rate of climate change.

The recently published National Food Strategy emphasised the importance of fruit and vegetables as a major part of our diets. Both fruit and vegetables provide essential vitamins, nutrients and fibres which consumed over time diminish the incidence of cancers, coronary, strokes and digestive diseases.

Apricots are high in catechins.

Eating varying types of fruit and vegetables increases their value – apricots, for example, are high in catechins which are potent anti-inflammatory agents. Members of the brassica (cabbage) family are exceptionally valuable for mitigating diseases of ‘modern society’. All contain glucosynolates, which evolved as means for combating pest and pathogen attacks and co-incidentally provide similar services for humans. Watercress – an aquatic brassica – is rich in vitamins A, C and E, plus folate, calcium and iron. Its high water content means portions consumed fresh or as soups are low in calories.

Watercress – an aquatic brassica boasts numerous health benefits.

These messages and facts are now being recognised both publicly and politically, and not before time. For the past 50 years the universal panaceas have been pharmaceutical drugs. In moderation, these have been of immense value. Use to excess is both counterproductive and needlessly expensive health-wise and financially.

Returning to Grandma’s advice, ‘an apple a day keeps the doctor away’, supports both individual and planetary good health.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

SCI was pleased to support #BlackInChem, working alongside our Corporate Partners and members to amplify the voices of our Black chemists.

We have heard stories from several Black chemists who highlighted the steps being taken by many companies to increase diversity. But we can also see that there are many more steps that can be taken to encourage the next generation of budding Black chemists and scientists.

#BlackInChem has had support from Scott Bader, an SCI Corporate Partner, with both Damilola Adebayo and Luyanda Mbongwa sharing their perspectives as employees of Scott Bader. Elsewhere, Cláudio Laurenço gave a compelling account of his journey to become a post-doctoral research associate at a leading consumer goods company.

Cláudio Laurenço worked for free and was overlooked before eventually securing his PhD and starting his career in chemistry.

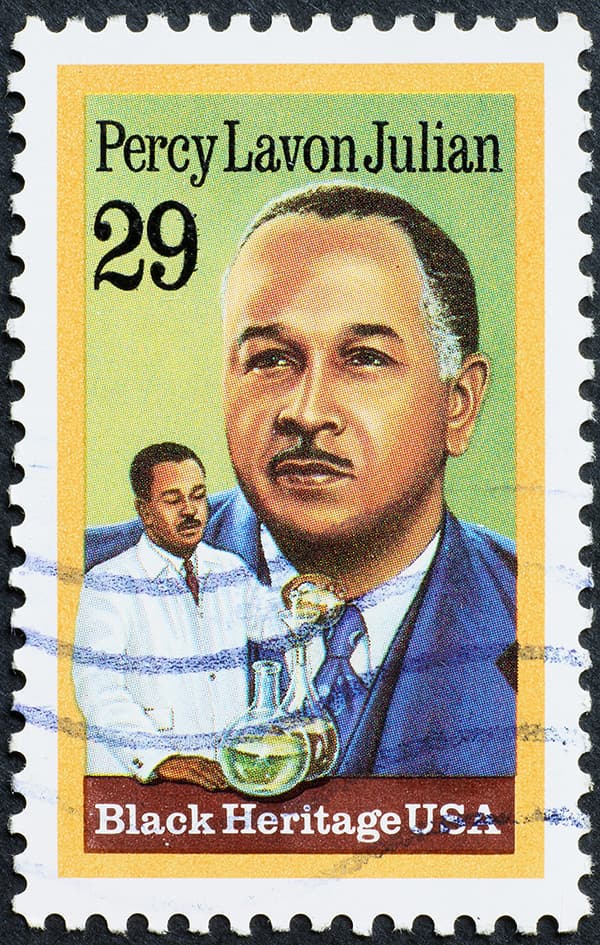

These chemists are following in the footsteps of some pioneering Black scientists such as Percy Lavone Julian, who has been profiled on the SCI Blog.

Many organisations have expressed their support and shared thoughts on what steps they are taking to encourage and ensure diversity. Indeed, #BlackInChem is a global effort and companies such as GSK have shown their support as well as numerous Black chemists talking about their experiences and achievements over the last week.

Percy Lavon Julian’s pioneering work enabled a step-change in the treatment of glaucoma | Editorial credit: spatuletail / Shutterstock.com

Over the coming months, we will be profiling other Black chemists, past and present, and continuing the dialogue around diversity.

>> We’re always keen to hear about diverse perspectives within chemistry. If you’d like to share your story, please contact: muriel.cozier@soci.org or eoin.redahan@soci.org.

For Cláudio Lourenço, the path from student to multidisciplinary scientist has been far from smooth. The Postdoctoral Research Associate reflects on the institutional challenges that almost made him give up, the mentor whose support was so important, and the barriers that block the way for young Black chemists.

Please give a brief outline of your role.

I work for a leading consumer goods company. I am a multi-disciplinary scientist contributing to the development of novel formulations for household products.

Why are you supporting #BlackInChem?

I’m supporting #BlackInChem because I am a champion for diversity. I believe that what we see from our windows in the street is what we must have inside our workplaces. In an ideal world we should all have the same opportunities, but unfortunately this is somehow far from the truth. We need to motivate our young Black chemists to aim for a career in science by providing welcoming environments and real opportunities instead of just ticking boxes. We need to showcase our Black chemists to show to the younger generation that they can also be one of us.

What was it that led you to study chemistry and ultimately develop a career in this field? Was this your first choice?

I have always been passionate about research and science. My father had a pharmacy, so I was always close to chemistry and was a very curious child. Yes, it was my first choice but the lack of opportunities and trust from universities and scholarship providers made it a long run. My motivation faded and I nearly gave up.

Was there any one person or group of people who had a specific impact on your decision to pursue your career path?

Yes, but after my degree I nearly gave up. It took me nearly two years and changing cities to find something (a voluntary position). I was always keen on taking up mentors to show me how to progress in my career. There were a few people who helped me by training me and teaching me how to navigate the scientific world and pursue a career in science.

I only got my first job (which I worked for free) because of Peter Stambrook, an American scholar from the University of Cincinnati, who I met through a friend while polishing glasses in a restaurant. This man was open and keen to put a word in for me at a leading university in the UK. He taught me so much on how to be a scientist and humbly grow up and make a career in science. Eventually, all his advice kept me on the right path.

What impact would you like to see #BlackInChem have over the coming year?

More Black students in postgraduate courses and an increase in role models to motivate the younger generations to pursue careers in chemistry.

Could you outline the route that you took to get to where you are now, and how you were supported?

Personally, my career path was far from easy. I only managed to get my PhD at 38 years of age. I needed to first prove myself. Despite all my efforts and dozens of applications, I was never considered a good candidate. I needed to work for free for two years to land a proper job in my field of choice. During that time I took on many odd jobs to support myself. I worked for a top 10 university for free and they never saw my worth or gave me an opportunity. With that experience I landed a proper job at a leading pharmaceutical company. After one year with them, they funded my PhD studies and now here I am with a career in science.

Considering your own career route, what message do you have for people who would like to follow in your footsteps?

Never ever give up - it is possible. Look for the right mentors and be humble. You do not need to reinvent the wheel, but only to find someone who can lend you theirs. Learn to grow from the experiences of others and be ready to fail a couple of times - we all do. Be open to learn and never be afraid of following your dreams.

>> At SCI, we’re proud to support #BlackinChem. Reach out to us with your stories.

What do you think are the specific barriers that might be preventing young black people from pursuing chemistry/science?

I think one of the biggest barriers that prevent people from pursuing careers in science is the lack of role models. If we only show advertisements for chemistry degrees with White people, it’s not encouraging for Black students to pursue a career there. The same goes for when we visit universities; role models are needed. No one wants to be the only Black person in the department. Universities need to embrace diversity at all levels. I understand that tradition sometimes prevents this, but we need to change and ignore tradition for a bit.

What steps do you think can be taken by academia and businesses to increase the number of Black people studying and pursuing chemistry/science as a career?

Showcase Black chemists and inventors to motivate the younger generations and show society that Black people are not only artists and musicians. Target extracurricular activities in schools where children are from disadvantaged backgrounds. Train your staff to be open. Create cultural events that not only target Black people but also for other people to learn and see that in the end we are all equal. We all need to learn to embrace our differences and grow together.

>> As we celebrate #BlackinChem, we mark the achievements of some inspirational chemists. Read more about the amazing career of Percy Lavon Julian.

This week SCI is joining with business and academia to mark #BlackInChem, an initiative to advance and promote a new generation of Black chemists.

Over the coming weeks, we shall be profiling past and present Black chemists, many of whom are unsung heroes, and whose work established the foundations on which some of our modern science is built. We start with the outstanding contribution made by Percy Lavon Julian (1899-1975).

Born on 11 April 1899 in Montgomery, Alabama, US, Percy L Julian was the son of a clerk at the United State Post Office and a teacher. He did well at school, and even though there were no public high schools for African Americans in Montgomery, he was accepted at DePauw University, Indiana, in 1916.

Due to segregation Julian had to live off campus, even struggling initially to find somewhere that would serve him food. As well as completing his studies, he worked to pay his college expenses. Excelling in his studies, he graduated with a BA in 1920.

Julian wanted to study chemistry, but with little encouragement to continue his education, based on the fact there were few job opportunities, he found a position as a chemistry instructor at Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee.

In 1922 Julian won an Austin Fellowship to Harvard University and received his MA in 1923. With no job offers forthcoming, he served on the staff of predominantly Black colleges, first at West Virginia State College and in 1928 as head of the department of chemistry at Howard University.

In 1929 Julian received a Rockefeller Foundation grant and the chance to earn his doctorate in chemistry. He studied natural products chemistry with Ernst Späth, an Austrian chemist, at the University of Vienna and received his PhD in 1931. He returned to Howard University, but it is said that internal politics forced him to leave.

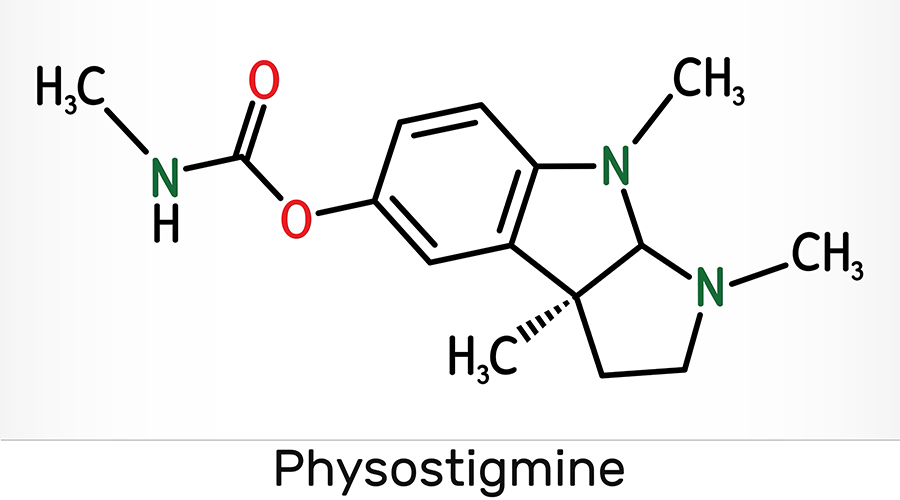

Physostigmine was synthesised by Julian

Julian returned to DePauw University as a research fellow during 1933. Collaborating with fellow chemist and friend Josef Pikl, he completed research, in 1935, that resulted in the synthesis of physostigmine. His work was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Physostigmine, an alkaloid, was only available from its natural source, the Calabar bean, the seed of a leguminous plant native to tropical Africa. Julian’s research and synthesis process made the chemical readily available for the treatment of glaucoma. It is said that this development was the most significant chemical research publication to come from DePauw.

Calabar bean

Once the grant funding had expired, and despite efforts of those who championed his work, the Board of Trustees at DePauw would not allow Julian to be promoted to teaching staff. He left to pursue a distinguished career in industry. It is said that he was denied one particular position as a town law forbid ‘housing of a Negro overnight.’ Other companies are also said to have rejected him because of his race.

However, in 1936 he was offered a position as director of research for soya products at Glidden in Chicago. Over the next 18 years, the results of his soybean protein research produced numerous patents and successful products for Glidden. These included a paper coating and a fire-retardant foam used widely in World War II to extinguish gasoline fires. Julian’s biomedical research made it possible to produce large quantities of synthetic progesterone and hydrocortisone at low cost.

Percy Lavon Julian | Editorial credit: spatuletail / Shutterstock.com

By 1953 Julian Laboratories had been established, an enterprise that he went on to sell for more than $2 million in 1961. He then established the Julian Research Institute, a non-profit research organisation. In 1967 he was appointed to the DePauw University Board of Trustees, and in 1973 he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, the second African American to receive the honour.

He was also widely recognised as a steadfast advocate of human rights. Julian continued his private research studies and served as a consultant to major pharmaceutical companies until his death on 19 April 1975. Percy Lavon Julian is commemorated at DePauw University with the Percy L Julian Science and Mathematics Center named in his honour. During 1993 the United States Postal Service commemorated Julian on a stamp in recognition of his extraordinary contribution to science and society.

Sometimes, when you try to solve one problem, you create another. A famous example is the introduction of the cane toad into Australia from Hawaii in 1935. The toads were introduced as a means of eliminating a beetle species that ravaged sugar cane crops; but now, almost a century later, Western Australia is inundated with these venomous, eco-system-meddling creatures.

In a similar spirit, disposable face masks could help tackle one urgent problem while creating another. According to researchers at Swansea University, nanoplastics and other potentially harmful pollutants have been found in many disposable face masks, including the ones some use to ward off Covid-19.

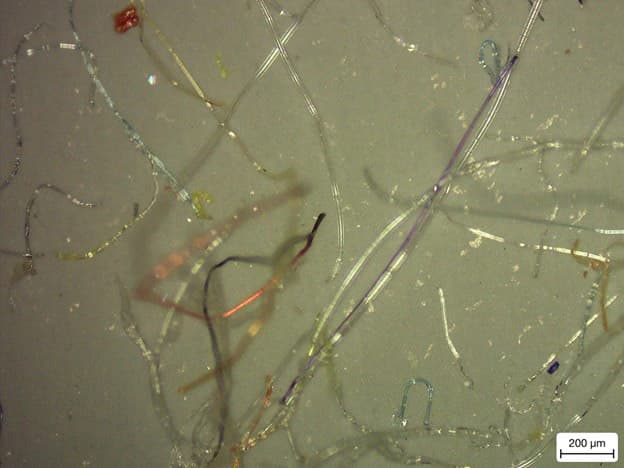

After submerging various types of common disposable face masks in water, the scientists observed the release of high levels of pollutants including lead, antimony, copper, and plastic fibres. Worryingly, they found significant levels of pollutants from all the masks tested.

Microscope image of microfibres released from children's mask: the colourful fibres are from the cartoon patterns | Credit: Swansea University

Obviously, millions have been wearing single-use masks around the world to protect against the Covid-19 pandemic, but the release of potentially harmful substances into the natural environment and water supply could have far-reaching consequences for all of us.

‘The production of disposable plastic face masks (DPFs) in China alone has reached approximately 200 million a day in a global effort to tackle the spread of the new SARS-CoV-2 virus,’ says project lead Dr Sarper Sarp, whose team’s work has been published on Science Direct. ‘However, improper and unregulated disposal of these DPFs is a plastic pollution problem we are already facing and will only continue to intensify.

The presence of potentially toxic pollutants in some face masks could pose health and environmental risks.

‘There is a concerning amount of evidence that suggests that DPFs waste can potentially have a substantial environmental impact by releasing pollutants simply by exposing them to water. Many of the toxic pollutants found in our research have bio-accumulative properties when released into the environment and our findings show that DPFs could be one of the main sources of these environmental contaminants during and after the Covid-19 pandemic.’

The Swansea scientists say stricter regulations must be enforced during manufacturing and disposal of single-use masks, and more work must be done to understand the effect of particle leaching on public health and on the environment. Another area they believe warrants investigation is the amount of particles inhaled by those wearing these masks.

‘This is a significant concern,’ adds Sarp, ‘especially for health care professionals, key workers, and children who are required to wear masks for large proportions of the working or school day.’

Many of us have contemplated buying a reconditioned phone. It might be that bit older but it has a new screen and works as well as those in the shop-front. I’m not sure, however, that any of us have thought of investing in a reconditioned liver – but it could be coming to a body near you.

Researchers based in São Paulo’s Institute of Biosciences have been developing a technique to create and repair transplantable livers. The proof-of-concept study published in Materials Science and Engineering by the Human Genome and Stem Cell Research Centre (HUG-CELL) is based on tissue bioengineering techniques known as decellularisation and recellularisation.

The organs of some donors are sometimes damaged in traffic accidents, but these may soon be transplantable if the HUG-CELL team realises its goal.

The decellularisation and recellularisation approach involves taking an organ from a deceased donor and treating it with detergents and enzymes to remove all the cells from the tissue. What remains is the organ’s extracellular matrix, containing its original structure and shape.

This extracellular matrix is then seeded with cells from the transplant patient. The theoretical advantage of this method is that the body’s immune system won’t rile against the new organ as it already contains cells from the patient’s own body, thereby boosting the chance of long-term acceptance.

However, the problem with the decellularisation process is that it removes the very molecules that tell cells to form new blood vessels. This weakens cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix. To get around this, the researchers have introduced a stage between decellularisation and recellularisation. After decellularising rat livers, the scientists injected a solution that was rich in the proteins produced by lab-grown liver cells back into the extracellular matrix. These proteins then told the liver cells to multiply and form blood vessels.

These cells then grew for five weeks in an incubator that mimicked the conditions inside the human body. According to the researchers, the results showed significantly improved recellularisation.

“It’s comparable to transplanting a ‘reconditioned’ liver, said Mayana Zatz, HUG-CELL’s principal investigator and co-author of the article. “It won't be rejected because it uses the patient’s own cells, and there’s no need to administer immunosuppressants.”

Extracellular matrix of a decellularised liver | Image Credit: HUG-CELL/USP

Obviously, there is a yawning gap between proof of concept and the operating theatre, but the goal is to scale up the process to create human-sized livers, lungs, hearts, and skin for transplant patients.

“The plan is to produce human livers in the laboratory to scale,” said lead author Luiz Carlos de Caires-Júnior to Agência FAPESP. “This will avoid having to wait a long time for a compatible donor and reduce the risk of rejection of the transplanted organ."

This technique could also be used to repair livers given by organ donors that are considered borderline or non-transplantable. “Many organs available for transplantation can’t actually be used because the donor has died in a traffic accident,” Caires-Júnior added. “The technique can be used to repair them, depending on their status.”

Even if we are at the early stages of this approach, it bodes well for future research. And for those on the organ transplant list, a reconditioned liver would be as good as a new one – complete with their very own factory settings.

Read the paper here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0928493120337814

Every day, there are subtle signs that machine learning is making our lives easier. It could be as simple as a Netflix series recommendation or your phone camera automatically adjusting to the light – or it could be something even more profound. In the case of two recent machine-learning developments, these advances could make a tangible difference to both microscopy, cancer treatment, and our health.

The first is an artificial intelligence (AI) tool that improves the information gleaned from microscopic images. Researchers at the University of Gothenburg have used this deep machine learning to enhance the accuracy and speed of analysis.

The tool uses deep learning to extract as much information as possible from data-packed images. The neural networks retrieve exactly what a scientist wants by looking through a huge trove of images (known as training data). These networks can process tens of thousands of images an hour whereas some manual methods deliver about a hundred a month.

Machine learning can be used to follow infections in a cell.

In practice, this algorithm makes it easier for researchers to count and classify cells and focus on specific material characteristics. For example, it can be used by companies to reduce emissions by showing workers in real time whether unwanted particles have been filtered out.

“This makes it possible to quickly extract more details from microscope images without needing to create a complicated analysis with traditional methods,” says Benjamin Midtvedt, a doctoral student in physics and the main author of the study. “In addition, the results are reproducible, and customised. Specific information can be retrieved for a specific purpose."

The University of Gothenburg tool could also be used in health care applications. The researchers believe it could be used to follow infections in a cell and map cellular defense mechanisms to aid the development of new medicines and treatments.

Machine learning by colour

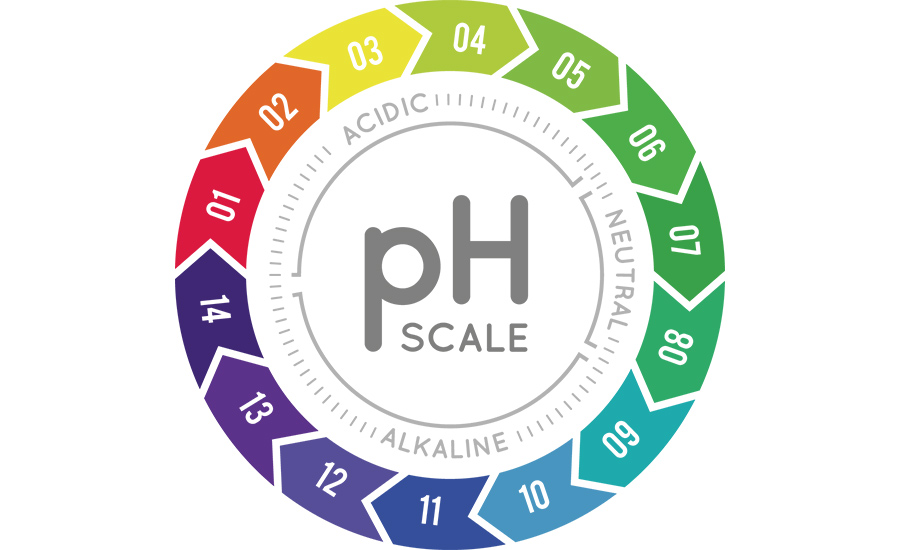

On a similar thread, machine learning has been used to detect cancer by researchers from the National University of Singapore. The researchers have used a special dye to colour cells by pH and a machine learning algorithm to detect the changes in colour caused by cancer.

The researchers explain in their APL Bioengineering study that the pH (acidity level) of a cancerous cell is not the same as that of a healthy cell. So, you can tell if a cell is cancerous if you know its pH.

With this in mind, the researchers have treated cells with a pH-sensitive dye called bromothymol blue that changes colour depending on how acidic the solution is. Once dyed, each cell exudes its unique red, green, and blue fingerprint.

By isolating a cell’s pH, researchers can detect the presence of cancer.

The authors have also trained a machine learning algorithm to map combinations of colours to assess the state of cells and detect any worrying shifts. Once a sample of the cells is taken, medical professionals can use this non-invasive method to get a clearer picture of what is going on inside the body. And all they need to do all of this is an inverted microscope and a colour camera.

“Our method allowed us to classify single cells of various human tissues, both normal and cancerous, by focusing solely on the inherent acidity levels that each cell type tends to exhibit, and using simple and inexpensive equipment,” said Chwee Teck Lim, one of the study’s authors.

“One potential application of this technique would be in liquid biopsy, where tumour cells that escaped from the primary tumour can be isolated in a minimally invasive fashion from bodily fluids.”

The encouraging sign for all of us is that these two technologies are but two dots on a broad canvas, and machine learning will enhance analysis. There are certainly troubling elements to machine learning but anything that helps hinder disease is to be welcomed.

Machine Learning-Based Approach to pH Imaging and Classification of Single Cancer Cells:

https://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/5.0031615

Quantitative Digital Microscopy with Deep Learning:

https://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/5.0034891

Rising anxiety about air pollution, physical, and mental health, exacerbated by Covid-19 and concerns about public transport, has seen an increase in the popularity of cycling around Europe, leading many cities to transform their infrastructure correspondingly.

These days, Amsterdam is synonymous with cycling culture. Images of thousands of bikes piled up in tailor-made parking facilities continue to amaze and it is routinely held up as an example of greener, cleaner, healthier cities. Because The Netherlands is so flat, people often believe it has always been this way. But, in the 1970s, Amsterdam was a gridlocked city dominated by cars. The shift to cycling primacy took work and great public pressure.

For some cities, however, the pandemic has provided an unexpected opportunity on the roads. Milan's Deputy Mayor for Urban Planning, Green Areas and Agriculture, Pierfrancesco Maran, has explained that, "We tried to build bike lanes before, but car drivers protested". Now, however, numbers have increased from 1,000 to 7,000 on the main shopping street. "Most people who are cycling used public transport before”, he said. “But now they need an alternative”.

Creating joined up cycling networks is a major challenge for urban planners.

In Paris, the Deputy Mayor David Belliard does not seem concerned that the city’s investment since the start of the pandemic will go to waste. “It's like a revolution," he said. “Some sections of this road are now completely car-free. The more you give space for bicycles, the more they will use it.” They are committed to creating a cycle culture, providing free cycling lessons and subsidising the cost of bike repairs. The city intends to create more than 650km of cycle lanes in the near future.

The success in these two cities has been supported by local government but it has also been fuelled by an understandable (and encouraged) avoidance of public transport and fewer cars on the road generally. Going forward, however, it seems likely that those last two factors won’t be present. So how do you create a cycling culture in your city in the long run?

The answer is both simple and difficult: cyclists (and pedestrians) need to have priority over cars. In Brussels, where 40km of cycle track have been put down in the last year, specific zones have been implemented where this is the case, and speed limits have been reintroduced across the city.

In Copenhagen, in the late 1970s, the Danish Cyclists’ Federation arranged demonstrations demanding more cycle tracks and a return to the first half of the century, when cyclists had dominated the roads. Eventually, public pressure paid off — although there is still high demand for more cycle lanes. A range of measures, including changes made to intersections, make cyclists feel safer and local studies show that, as cyclist numbers increase, safety also increases. In many parts of the city, it is noticeable how little of the wide roads are actually available to cars: bikes, joggers, and pedestrians are all accommodated.

Segregated cycleways, like this one in Cascais, Portugal, make people more likely to cycle.

But, if you were starting from scratch, you might not simply add cycle lanes to existing roads and encourage behavioural changes on the road. Segregated, protected bike lanes like those introduced in Paris are the next level up and the results suggest they work — separated from the roads, more people are inclined to try cycling.

Dutch experts suggest, where possible, going even further. Frans Jan van Rossem, a civil servant specialising in cycling policy in Utrecht, believes the best option is to create solitary paths, separated from the road by grass, trees, or elevated concrete. Consistency is also important. Cities need networks of cycle tracks, not just a few highways. Again, prioritising cyclists is key to the Dutch approach. Many cities have roads where cars are treated as guests, restricted by a speed limit of 30km/hour and not permitted to pass. Signage is also key.

In London, Mayor Sadiq Khan’s target is for 80% of journeys to be made by walking, cycling, and/or public transport by 2041. Since 2018, the city has been using artificial intelligence to better understand road use in the city and plan new cycle routes in the capital. However, the experience of other European capitals suggests that, "if you build it, they will come" might be a better approach than working off current usage.

More people are looking at their nutritional intake, not only to improve wellbeing but also reduce their environmental impact. With this, comes a move to include foods that are not traditionally cultivated or consumed in Europe.

Assessing whether this growing volume of so called ‘novel foods’ are safe for human consumption is the task of the European Food Safety Authority. The EFSA points out, ‘The notion of novel food is not new. Throughout history new types of food and food ingredients have found their way to Europe from all corners of the globe. Bananas, tomatoes, tropical fruit, maize, rice, a wide range of spices – all originally came to Europe as novel foods. Among the most recent arrivals are chia seeds, algae-based foods, baobab fruit and physalis.’

Under EU regulations any food not consumed ‘significantly’ prior to May 1997 is considered to be a ‘novel food’. The category covers new foods, food from new sources, new substances used in food as well as new ways and technologies for producing food. Examples include oils rich in omega-3 fatty acids from krill as a new source of food, phytosterols as a new substance, or nanotechnology as a new way of producing food.

Providing a final assessment on safety and efficacy of a novel food is a time consuming process. At the start of 2021 the EFSA gave its first completed assessment of a proposed insect-derived food product. The panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens concluded that the novel food dried yellow meal worm (Tenebrio molitor larva) is safe for human consumption.

Dried yellow meal worm (Tenebrio molitor larva) is safe for human consumption, according to the EFSA.

Commenting in a press statement, as the opinion on insect novel food was released, Ermolaos Ververis, a chemist and food scientist at EFSA who coordinated the assessment said that evaluating the safety of insects for human consumption has its challenges. ‘Insects are complex organisms which makes characterising the composition of insect-derived products a challenge. Understanding their microbiology is paramount, considering also that the entire insect is consumed,’

Ververis added, ‘Formulations from insects may be high in protein, although the true protein levels can be overestimated when the substance chitin, a major component of insects’ exoskeleton, is present. Critically, many food allergies are linked to proteins so we assess whether the consumption of insects could trigger any allergic reactions. These can be caused by an individual’s sensitivity to insect proteins, cross-reactivity with other allergens or residual allergens from insect feed, e.g. gluten.’

EFSA research could lead to increased choice for consumers | Editorial credit: Raf Quintero / Shutterstock.com

The EFSA has an extensive list of novel foods to assess. These include dried crickets (Gryllodes sigillatus), olive leaf extract, and vitamin D2 mushroom powder. With the increasing desire to find alternatives to the many foods that we consume on a regular basis, particularly meat, it is likely that the EFSA will be busy for some time to come.