British beer-sellers are expected to sell roughly 7-800,000 more barrels of beer during December than any other month of the year, according to the British Beer & Pub Association (BBPA). And since every barrel holds 288 pints, it is clear that the UK consumer still has an appetite for beer – albeit sales fell by 6% in 2009, which was the sharpest year-on-year decline since 1948, BBPA reports.

But beer tastes have changed markedly in recent years. As well as a growing enthusiasm for real ales, produced by dedicated microbreweries, there are a huge number of ‘flavoured’ beers containing aroma-contributing materials other than cereal, hops, yeast and water alone. And the trend for flavoured beers is growing, particularly in the newer breweries in the craft sector, as they search for new angles, new opportunities and the seemingly inevitable desire to push the boundaries. Some are pretty traditional – for instance, the fruit-containing Lambics of Belgium – kriek, cassis and so on – and the Michelada of Mexico with tomatoes, as well as the Belgian Wit beers.

These beers are an opportunity for brewers to give vent to their creative spleen. In the winter there is a tradition of producing more alcoholic beers with rich colours and flavours. There are no hard or fast rules. The phrase ‘Winter Warmer’ is sometimes associated with this type of product, particularly over the festive season, inferring a higher alcohol level. And in the spirit of Christmas pudding and mulled wine then you might expect some fruit and spices in the mix.

It is very easy to be sniffy about flavoured beer – and I myself have gone on record as wishing that brewers would make more of the malts, hops and yeasts available to them in preference to ever wackier additions. But it is too easy to be snooty. And provided a product is drinkable and sensible then it all adds to the rich tapestry that is beer and brewing.

The British have long liked their lager and lime, mixed in the glass. Citrus beers melded in the brewery are now commonplace. Then we have chilli beers, and beers with oyster essence, and pumpkin ales – not new incidentally, as the early US settlers already produced these – and even beers with guarana, caffeine and ginseng. The possibilities are endless.

When I was research manager for Bass in the 1980s we had a very active new product development portfolio. We worked on novel beers – and other alcoholic beverages that included products with fruity flavours such as Hooper’s Hooch. I recall a citrus beer that we developed, as well as a non-alcoholic drink that had the taste and aroma of prawn cocktail. I loved it, but what I like and what others like do not always coincide. Vive la différence!

Good beer is what you think it is. The consensus would be that it is beer that looks good – stable foam, correct and appealing colour for the genre, the correct degree of clarity for that product and the flavour spectrum expected in that style. But naturally it is subjective: a modestly foaming pint of cask ale in London will not appeal to a German expecting lashings of bubbles and a somewhat cooler brew.

The biggest challenge today is flavour stability. Most beers are never better than when first brewed, because they are prone to oxidation and other reactions that change their flavour. So it is a movable feast. Beers that are shipped vast distances through extremes of temperature will develop nuances of cardboard, 'tomcat pee', sherry and more. So a beer that tastes like it was intended in, say, the Czech Republic will taste very different when it arrives in Chicago. The problem is: what does the customer expect? That drinker in Chicago might well like the aged notes – though most professional brewers would not – and if he pitched up in Prague might say ‘hey, this is not what this beer is supposed to taste like!’

Years ago, when I was QA manager in a big brewery that was part of the Bass group, we were told to bring our lager into a better match with the same lager brewed in other breweries. We did – and then our customers started to complain. So beer flavour as it is stored is a moveable feast. Most brewers would seek to minimise the changes that occur – but it is very hard once the beer has left the brewery.

Brewers have improved their brewing operations and packaging procedures to minimise oxygen levels. The problem remains of air ingress between the glass rim and the crown cork – pry-off caps allow less air ingress than twist offs. There are crown corks that incorporate oxygen scavengers. If it was economically feasible, the beer would always be shipped and stored refrigerated and with minimum agitation.

The British have long liked their lager and lime, mixed in the glass. Citrus beers melded in the brewery are now commonplace. Then we have chilli beers, and beers with oyster essence, and pumpkin ales – not new incidentally, as the early US settlers already produced these – and even beers with guarana, caffeine and ginseng. The possibilities are endless.

But in truth it was ever thus. The earliest alcoholic brews were likely not wholly either fruit or grain-based, but probably contained both cereal and fruit in the mix. And they were flavoured with all manner of things, including poisonous mandrake plants. Likewise, in medieval times beers were flavoured with proprietary blends of herbs and spices called gruit – things like bog myrtle, coriander, yarrow, heather, juniper etc. The early Americans spiced their beers with spruce. The business of choosing new flavours to add is a matter of trial and error. And perhaps an eye on the historical record. Personally I am not big on caffeine and chilli in beer. I love the fruited Belgian Lambics.

When I was research manager for Bass in the 1980s we had a very active new product development portfolio. We worked on novel beers – and other alcoholic beverages that included products with fruity flavours such as Hooper’s Hooch. I recall a citrus beer that we developed, as well as a non-alcoholic drink that had the taste and aroma of prawn cocktail. I loved it, but what I like and what others like do not always coincide. Vive la différence!

Good beer is what you think it is. The consensus would be that it is beer that looks good – stable foam, correct and appealing colour for the genre, the correct degree of clarity for that product and the flavour spectrum expected in that style. But naturally it is subjective: a modestly foaming pint of cask ale in London will not appeal to a German expecting lashings of bubbles and a somewhat cooler brew.

Creating the newer spicy or flavoured beers does not present any particular challenges. It is just a case of working out how to achieve the desired goal; how to add the materials and so on. Are these additions readily available? How do you quality control them?

The biggest challenge today is flavour stability. Most beers are never better than when first brewed, because they are prone to oxidation and other reactions that change their flavour. So it is a movable feast. Beers that are shipped vast distances through extremes of temperature will develop nuances of cardboard, 'tomcat pee', sherry and more. So a beer that tastes like it was intended in, say, the Czech Republic will taste very different when it arrives in Chicago. The problem is: what does the customer expect? That drinker in Chicago might well like the aged notes – though most professional brewers would not – and if he pitched up in Prague might say ‘hey, this is not what this beer is supposed to taste like!’

Years ago, when I was QA manager in a big brewery that was part of the Bass group, we were told to bring our lager into a better match with the same lager brewed in other breweries. We did – and then our customers started to complain. So beer flavour as it is stored is a moveable feast. Most brewers would seek to minimise the changes that occur – but it is very hard once the beer has left the brewery.

Brewers have improved their brewing operations and packaging procedures to minimise oxygen levels. The problem remains of air ingress between the glass rim and the crown cork – pry-off caps allow less air ingress than twist offs. There are crown corks that incorporate oxygen scavengers. If it was economically feasible, the beer would always be shipped and stored refrigerated and with minimum agitation.

At 20oC storage, the rule of thumb would be three months’ shelf life for flavour, or longer for clarity. You can speed up the ageing rate three-fold for every 10oC rise in temperature, so in my garage in Davis, California, US, where temperatures can exceed 40oC in the summer, the beer is being cooked in a few days. But equally, refrigerated beer at 0-4oC will resist deterioration for much more than a year.

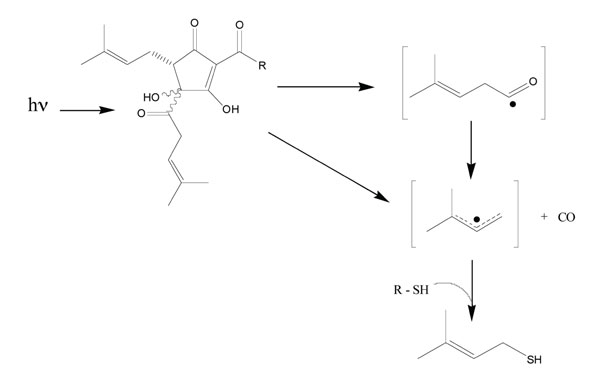

In terms of bottle colour, then brown is best. This restricts the access of light in the 350-500nm range, which would otherwise be captured by riboflavin (vitamin B2) in the beer and transferred to the hop bitter acids that break down to give 'skunky' flavour. Green glass or clear glass offers no protection against this. At least one brewer of beer packaged into clear glass employs hop. bitter acids that are reduced with hydrogen. These modifi ed hops do not generate 'skunky' character – moreover they are potent foam stabilisers.

All beer should be served properly in a sparkling clean glass, ideally one that is marketed alongside the beer and intended for it. Glasses should be washed in the sink with your favourite detergent but then rinsed thoroughly with totally clean, detergent-free water. You should then allow them to dry by draining. And you might even score a little scratch on the bottom of the glass on the inside as that will promote bubble formation – otherwise known as ‘beading’.

Don’t hesitate in pouring the beer with vigour into the centre of the glass. You will get lots of foam, but as it slowly subsides through liquid draining from it, the cereal proteins and the bitter acids stick together in the bubble walls and produce a nice stable foam, which will give a lovely lacing pattern as the beer is drunk. Once you have made this initial stable foam it is time to top up the beer more gently from the bottle. Voila: one of the most beautiful sights you can see.

The foam is always threatened by lipids and detergents. That is why you have the glass-cleaning ritual that I mention. It is also why I don’t have a moustache – all that grease dripping into the beer. And never, but never, wear lipstick.

The flavour is hugely important – and is infl uenced indirectly by the appearance of the beer. If a drinker is confronted by beers with and without foam, for instance, they will tend to score higher the fl avour of the beer with the head. Brewers control aroma and taste on the basis of instrumental and organoleptic methods. Using gas chromatography, high performance liquid chromatography, GC-olfactometry and so forth, they can research the key fl avour contributors and then use these instruments to quality control the ones that are of most concern.

An example would be the measurement of dimethyl sulphide, which is considered a plus in many lagers in modest amounts but a 'no-no' for most beer. Isoamyl acetate – banana aroma – features in many beers. Again it needs to be controlled to a specified level – not too little, not too much. But controlled it is – by brewing conditions, yeast handling, fermentation control etc. It’s not like wine, where batch-to-batch variation is celebrated as ‘vintage’.

In the beer world, every batch needs to be vintage – consistently excellent with no surprises. Other volatiles include diacetyl and pentanedione – butterscotch and honey, respectively – which are detested in most brews. Brewers know how to ensure they are avoided.

The most sensitive tools, though, are the human senses. Brewers do a huge amount of tasting. They taste the raw materials – especially water – to ensure they are free from taints. They taste samples throughout the processing. And they taste the finished beer to ensure everything is in order. Tasting is also done by expert trained panels –a team of individuals recruited for their ability to discern and score a multitude of flavour terms.

The first rule of thumb when selecting a beer is to choose the one that sits right with you. But if you do get hung up on specifi c beers that marry with given food courses, then I suggest a nice Helles with the Christmas turkey and a barley wine with the pudding?

And bear in mind that beer is more nutritious than wine. It contains a lot more silicon important for bone health, B vitamins, and fi bre. It contains an antioxidant, ferulic acid, that we know is assimilated by the body; in fact, there are questions about how much of those big polyphenols in wine actually ‘hit the spot’. And it is now known that the active ingredient countering atherosclerosis is alcohol, not some unique component – resveratrol – from grapes.

Some people argue that beer contains materials that variously promote lactation and counter dental caries. And of course, beers incorporate hops, and there has been more than the occasional suggestion that these have mellowing influences on the human psyche. Oh yes, beer wins over wine hands down. It’s more fun, too – and wholly less pretentious.

Charlie Bamforth is professor of food science and technology at the University of California, Davis, US.