Relations between the automotive and chemical industries have reached an impasse, but, as Thorsten Ploss explains, there may be a way forward

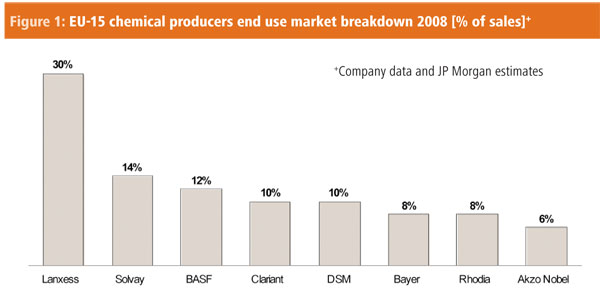

With 5% of the EU’s chemicals consumed by the automotive sector in Europe, plus a significant export share, chemicals producers have a material interest in a strong automotive industry. Companies like Lanxess, BASF and Solvay, for example, derived more than 10% of their sales from the automotive industry in 2008, while speciality players such as DSM also have significant exposure (Figure 1). However, the global recession has hit auto firms hard, leading to a sharp decline in vehicle sales, which quickly forced Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) to scale back production. This in turn has had a big impact on chemicals, significantly reducing demand for plastics, coatings, rubber and textiles and so on.

Long-term impact

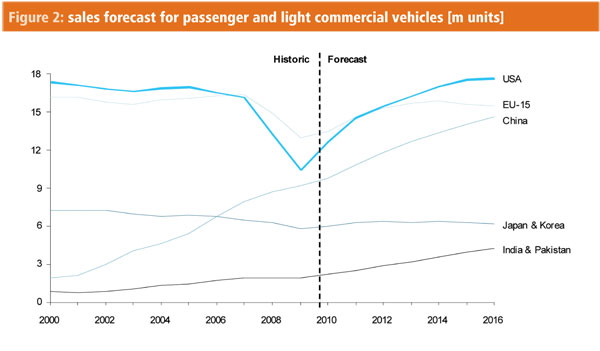

While government stimulus packages helped to buoy passenger vehicle production in 2009, questions remain over their long-term impact. Market research firm Frost & Sullivan, for example, reports that global passenger vehicle production is likely to experience a fall in compound annual growth rates (CAGR) of 4.1% between 2007 and 2010 (Figure 2): a sombre outlook for chemical companies selling into the automotive market.

One consequence of the demand collapse is that all players in the automotive value chain have reduced their inventories to free up cash and increase liquidity. The impact of this reduction in inventory levels becomes increasing magnified moving further along the value chain. The 11% reduction in year-to-date new car registrations in Europe actually leads to a demand reduction that is three to four times greater for European chemical companies at the beginning of the value chain.*

Fortunately, the destocking effect is a one-off impact that has already worked its way through the value chain. Although chemical companies should enjoy a small rebound in demand as some companies rebuild their inventory levels in the future, levels will not fully rebound to prerecession levels.

The reduction in chemical demand has been combined with increasing margin pressure, with the bankruptcy of two of the Big Three automotive companies in the US – GM and Chrysler – sending profitability shockwaves through the entire supply chain.

In reality, chemical companies were already facing increasing margin pressure well before the deterioration of the automotive industry. This was caused by two unrelated factors: the ‘Lopez effect’; and overcapacity in the polymer industry as a result of recent large-scale capacity additions in the Middle East, based on low feedstock costs.

Jose Ignacio Lopez de Arriortua made his name in the auto industry in the 1980s at GM’s Saragossa production plant in Spain, where he was mainly focused on saving costs and increasing competitiveness against Japanese manufacturers. Much of Lopez's efforts were directed at the supply chain and he introduced a full cost cutting programme when he moved to Russelsheim, Germany, to run Opel parts purchasing.

At Opel, Lopez revolutionised the production supply chain by setting prices on what clients would accept, not on production costs. He not only demanded massive cuts from the supply chain but also sent in his own specialists to identify how cuts could be achieved. During the 1990s, Lopez moved back to GM and then on to Volkswagen, installing his ‘Purchased Input Cost Optimisation with Suppliers’ teams along the way. The chemical industry has never fully recovered from the ‘Lopez effect’ and has limited confidence in regaining acceptable margins for new developments.

The second factor stems from the cyclicality of the petrochemical industry, whereby large stepwise capacity additions periodically exceed gradual demand increases. The current crisis coincides with large amounts of new steam cracker and polymer capacity, either based on low-cost Middle Eastern feedstock or located directly in the fast growing market, China. While the effect differs between polymers, the margins will be low for all Western producers.

When the auto industry collapsed and some OEMs started filing for bankruptcy, there was little or no financial headway available to suppliers to allow them to weather the storm. Major parts producers, such as Metaldyne and Visteon, have already filed for bankruptcy and the collapse has worked its way along the supply chain. Collapsed polymer demand was the final ‘nail in the coffin’ for the previously troubled LyondellBasell, which filed for bankruptcy in late 2008.

The margin pressure in the supply chain, coupled with the large-scale volume reductions, has made the automotive industry an unattractive end use market for chemical companies.

Challenges arising

The automotive and chemical industries have not shared an integrated approach in addressing automotive industry trends. The key success factors for the European chemical industry have changed radically over time: from a focus on ‘new products’ to ‘meeting requirements at lowest cost’. This shift is accelerated by the increasing production of commodities in the Middle East and the drive by emerging markets, namely China and India, to gain independence from imports.

The objectives of a typical automotive OEM, on the other hand, are threefold. First, it wants to decrease costs so that it can maintain or return to profitability. Second, it wants to produce products that fulfil its customers’ demand while also abiding by local government regulations. Third, it seeks global standardisation so that it can produce its product for as many automotive markets as simply and cost effectively as possible.

Both industries are keen to avoid a exclusive long-term contract that would lock them into specific supplier relationships.

Unfortunately, neither industry is currently successful at achieving their respective objectives. OEMs, for example, are struggling to remain profitable, partly causing many chemical companies' automotive margins to be unreliable. As a result, chemical companies are reluctant to invest in automotive chemicals and consider it as a market with limited potential. Instead, they are trying to cross-sell their current products so that they can achieve their goal of maximising their existing assets.

As the head of procurement at an Indian automotive OEM stated: ‘They [chemical companies] always want to sell what was developed for other industries.’ Automotive OEMs, on the other hand, want specialised chemicals for their specific needs. ‘Look at the steel industry,’ said one European OEM development executive, ‘they develop specific solutions to support our strategic goals. We don't see this in chemicals.’

Unfortunately, many Western OEMs have developed vehicles that customers are no longer interested in and have had trouble adjusting to regional regulations. This exacerbates OEM demand for further specialised chemicals customised for new preferences and regional regulations. However, the current state of the automotive industry just makes chemical companies more sceptical and more reluctant to invest in R&D to develop the required products.

Furthermore, automotive OEMs are frustrated by the lack of visibility about possible new materials and chemical compounds. Conversely, chemical companies complain that they are currently involved too late in the OEM innovation cycle, and say that the OEMs' ‘model-based’ innovation approach as it does not lend itself to more long-term development of new materials and chemicals. ‘They are not interested in fairness – just to squeeze a couple of cents out of our margin,’ according to the head of automotive at one EU chemicals producer.

Underlying problems

This friction between the automotive and chemical industries is indicative of deeper underlying problems. To understand these it is useful to identify the current structural relationship between OEMs, Tier 1 and 2 suppliers and chemical companies. At present, the structure is rather divisive. OEMs and Tier 1 and 2 suppliers are integrated closely along the value chain, working together to select materials, design parts and develop the end vehicle.

Any discussions regarding material selection, however, do not automatically involve chemical companies. Instead, chemical firms have their own one-to-one discussions with the Tier 1 and 2 suppliers on materials and potential chemical industry solutions.

Evidence for this OEM and chemical company isolation revealed itself repeatedly in interviews during a recent study by Roland Berger Strategy Consultants, in cooperation with the European Chemical Marketing and Strategy Association (ECMSA). To quote the head manager of interiors at a Chinese/Western OEM JV: ‘[Chemical companies] hardly ever talk to us, maybe once a year they run a public sales show but they never ask what we need’. The majority of European chemical producers do not set up internal structures addressing the automotive industry. ‘If we would talk directly to OEMs we would get in trouble with our customers [Tier 1 suppliers],’ wrote one business unit head at an EU chemicals producer.

The two industries have a history of poor communication. This leads to an inability to solve problems but, more importantly, increases the level of isolation of their respective companies. Misinformation is leading to a situation where each industry is ignorant of the other's capabilities.

Finally, the rapid deterioration of the automotive industry has heightened the focus on short-term objectives and decreased the attention paid to long-term, strategic thinking. Automotive OEMs, for example, are highly focused on the next models and modules they will develop. They are not approaching the chemical industry with a longterm R&D development plan that will innovate their entire product range not just individual vehicle models. At the same time, chemical companies are not working together to establish long-term development programmes that can create next generation materials for the automotive industry.

One of the key expectations of the European chemical industry is to get direct access to OEMs in order to get clear guidance on long-term requirements and justify automotive-focused R&D activities. Similar to OEMs, chemical companies require clear contact points, not only lead engineers working on the next model(s) but also decision makers for strategic developments.

The key success factor for the European chemical industry to invest in automotive-specific R&D is secured volumes over a longer period. The current perception is that there is a high risk that once the automotive industry receives the initial developments it will quickly switch to sourcing the products from low-cost supplier, say, in the Middle East.

Money that could potentially be spent on automotive R&D has to compete with other R&D opportunities for potentially more profitable and less price-sensitive industries. Without healthy returns over the R&D payback period and potential production asset investment, the chemical industry will not be able to invest in automotive-specific solutions.

Fusing the value chains

From the present state of limited interaction and engrained mistrust, it is clear that implementing a new cooperation model will need to be a stepby- step process. At Roland Berger, we suggest a four-step process as outlined below.

I OEM inclusion: A first step for enhanced cooperation is regular, direct contact of individual chemical companies and OEMs on a technical and senior management level. The goal should be to involve the chemical industry earlier in the innovation cycle of upcoming models and give direction to material decisions during the early design phase.

II. Strategic focus: The next step is to enhance cooperation and focus on strategic issues, for example, discussing material trends before beginning the design phase of individual models. While the previous step was based on individual relationships between chemical companies and OEMs the discussions of long-term strategic applications of chemical products may be better channelled through associations.

III. Business case driven: While step II identifies OEMs' long-term needs and opportunities for chemical producers, step III addresses the need to develop automotive specific materials/products.

Competing demands for R&D spending

IV. Value chain fusion: Finally, in the longterm, the value chain can be fused. One possible option is that the basic research for new, automotive-specific materials can be conducted by a consortium of chemical companies. Final product development, sales and marketing can then be done by individual chemical companies through direct interaction with OEMs and Tier 1 and 2 suppliers. Ultimately this approach could even lead to the initial production of a chemical precursor – for example, a new base polymer – by the consortium and the downstream processing by individual companies.

The main advantage of such fusion is the pooling of resources – not only financial but also intellectual. The approach also assures OEMs that they can include new, innovative materials in their strategic planning without becoming dependent on a single player or a monopoly.

Thorsten Ploss is a partner at Roland Berger Strategy Consultants based in London, UK.