Katrina Megget

The holy grail of an on-demand contraceptive for men is a step closer after scientists were able to stop sperm from swimming in mice.

The research out of Weill Cornell Medicine, at Cornell University, New York, US, highlights a new approach to male contraceptives, targeting a cellular signalling enzyme rather than the more traditional approach of attempting to mimic the female hormonal contraceptive pill.

The results in mice suggest the sperm are immobilised for several hours before returning to normal around 24 hours later. If a pill could be developed, men would only need to take it when they need it – a benefit that a hormonal contraceptive would not have.

That’s because sperm take 10 weeks to mature, explains Jochen Buck, Professor of pharmacology at Weill Cornell Medicine. A hormonal contraceptive aims to stop the production of sperm, so any hormonal contraceptive would not be effective until 10 weeks after taking it. The onus is then on the man to continually take the contraceptive, he says.

The non-hormonal contraceptive effectively immobilised mouse sperm for around 24 hours.

‘Our approach is radically different. Our approach is blocking the “on switch” for the movement of sperm. We can block movement as fast as the drug inhibits the enzyme – 15 minutes to half an hour based on the administration method,’ Buck says.

In addition, an on-demand, non-hormonal pill would mean none of the side effects that might be associated with hormonal contraceptives, Buck notes. ‘This is why people are so excited about our finding.’

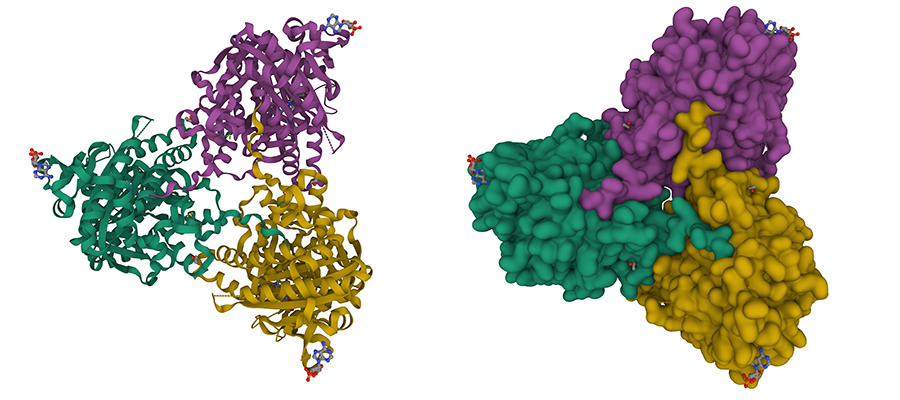

The experimental pill, called TDI-11861, targets a specific cellular signalling enzyme called soluble adenylyl cyclase or sAC. Research shows sAC, which is expressed in high levels in sperm, is the “on switch” for sperm to swim. Normally it’s activated when sperm are mixed with semen during ejaculation.

Soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) a regulatory cytosolic enzyme present in almost every cell and is essential for sperm motility and maturation.

The pill that Buck and his team have developed is a sAC inhibitor and works by blocking the sperm’s ability to swim. In their research in mice, they found a single dose of the drug renders male mice temporarily infertile by immobilising the sperm for around three hours. The mice still exhibited normal mating behaviour and full fertility returned 24 hours later.

Buck says studies are now being conducted in rabbits and the plan is to have the first proof-of-principle trial testing male human sperm in two to three years. A product that men could take about 30 minutes before sex could be on the market in seven-to-eight years, he believes.

‘Over 50% of pregnancies aren’t planned and neither men nor women are totally content with the options,’ he says. ‘At the moment, all that’s really available for men [besides vasectomy] is condoms and no one really likes them.’

The first female contraceptive pill was marketed in 1960.

Christina Wang, Associate Director, Clinical and Translational Science Institute at The Lundquist Institute and professor of medicine at UCLA, California, US, has several hormone-based drugs in clinical trials but notes an on-demand contraceptive is an interesting concept.

Richard Anderson, Elsie Inglis Professor of clinical reproductive science and Co-director of the Centre for Reproductive Health at the University of Edinburgh, UK, agrees: ‘There is always a need for more and effective contraceptive choices to help couples find the method that’s best for them. A non-hormonal method would be great, but they are all animal studies [at the moment]. It’s exciting but a long way to go.’

A male contraceptive could be a game changer. While the female version hit the market in the early 1960s and changed women’s lives forever, a male contraceptive has remained elusive despite research dating back to the 1970s. This is partly due to funding problems and minimal interest by big pharma but also the challenges of needing to stop millions of sperm being produced every day versus one egg released every 28 days, explains Anderson.

Yet there has been more research in recent years, and numerous studies suggest there is demand for a male contraceptive as well as increasing numbers of women saying they would trust men to take one.

Most research remains focused on hormone-based approaches to suppress sperm production – for instance, Wang has an oral preparation and transdermal gel in Phase 1 and Phase 2b trials, respectively, while the University of Edinburgh also has a transdermal gel being tested in men. More research, however, is beginning to look at non-hormonal approaches.