Legal highs, the drugs that stay the right side of the law, take their inspiration from obscure pharmaceutical research. Lou Reade reports

The recent banning of the drug mephedrone – after it was implicated in the deaths of several young people in the UK – has brought the issue of ‘legal highs’ into the public eye. Legal highs provide some of the effects of restricted drugs, such as ecstasy or cocaine, but are different enough in chemical structure to stay the right side of the law. Until April, mephedrone fell into this category. As a cathinone, it is chemically related to amphetamines like ecstasy. According to the Home Office’s drugs awareness website, Frank, its effects are ‘similar to cocaine, ecstasy and amphetamines’.

Not for human consumption

Most legal highs are bought on the internet. They are often advertised as ‘plant food’ that is ‘not for human consumption’. They also claim to have no dangerous side effects, but anecdotal evidence suggests that mephedrone can cause drowsiness, paranoia and seizures.

Following the deaths, mephedrone was rapidly classified as a Class B drug, putting it on a par with cannabis. But as one legal high disappears, new ones will come onto the market.

‘There are people out there who say, “I can design a molecule that falls outside the legislation, but still has an effect”,’ says Ric Treble, scientific advisor at the UK Laboratory of the Government Chemist.

Just as pharmaceutical companies sift through many different compounds in the quest for a blockbuster drug, so designers of legal highs will look at a range of potentially active compounds, based on their similarity to other drugs. And their inspiration often comes from an unlikely source.

‘There is a lot of quite obscure research on neurochemistry and psycho-active materials,’ says Treble. ‘This is academic research work. The pharmaceutical industry has a legitimate interest in discovering these things, but some of the information is leaking out.’

For those who want to develop legal highs, medical journals are a fruitful source of research as they will include papers on serotonin receptors, mood enhancers, anti-depressants and a wealth of other topics.

One legal high that has recently raised its head above the parapet is 5,6-methylenedioxy- 2-aminoindane (MDAI) which, Treble says, derives from a ‘classical piece of pharmaceutical research’. David Nichols, of Purdue University in the US, is a leading pharmacology researcher and his team synthesised several derivatives of the amphetamine MDA, including MDMA (ecstasy) and MDAI. Nichols is one of many legitimate researchers into these substances, which could be used to treat medical conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

MDAI is a ‘conformationally restricted’ version of MDA: a methyl group has been attached to the benzene ring to give a more constrained structure – an indole ring. While it has a less profound effect than MDA, it is known to be less neurotoxic.

‘He’s made MDAI in the course of his research, and published his findings,’ says Treble. ‘Somebody has drilled down into it and thought, “This could have a market.”

A ‘bible’ of the legal highs industry is Pihkal – an acronym for Phenethylamines I Have Known And Loved – by Alexander Shulgin, which is effectively a recipe book for a range of chemical compounds. One look at the entry on MDAI, for example, shows that it is no mean feat to produce a sample.

‘MDAI is quite a small molecule – less than 12 carbon atoms – but you’d need a bit of technical skill to produce it,’ says Treble.

Another legal high that has come to the fore, since mephedrone became illegal, is NRG-1. Its chemical name is naphyrone and, like mephedrone, it is a cathinone. It is reputed to have begun life as an appetite suppressant. The structures of the two compounds are similar in that both include a ketone group and an aminelike group. In fact, a website selling naphyrone, or ‘plant food’, to use the recognised code, simply uses a picture of its chemical structure.

Legal highs like MDAI and NRG-1 are so new that the long-term effects are unknown. And keeping track of the many new compounds can be very difficult.

‘The term I use is a chemical arms race,’ says Treble. ‘As fast as we can control materials, people are coming up with new substances.’

One way that the authorities build up a picture of the legal highs ‘pipeline’ is to monitor the internet as this is how most of the products are sold. The Psychonaut programme, which is centred in Portugal, monitors the internet for the appearance of new drugs. It looks at which materials are being offered for sale, or are being discussed in chat rooms.

Psychonaut is run by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), which itself uses toxicology and forensic reports to build up a picture of which substances are being used. Some, like mephedrone, find their niche in the market until they are banned. ‘Many others are reported once or twice, then are never seen again,’ Treble says.

In its latest report, the EMCDDA says it recorded 24 new psychoactive drugs in 2009 – the highest ever reported in a single year. One of these was mephedrone. Others included synthetic cannabinoids – effectively ‘synthetic cannabis’.

The suspicion is that production is carried out in the Far East – most probably China. This is because the types of businesses that can make ‘off licence’ pharmaceutical products are in a perfect position to make ‘legal highs’ too.

Speaking to satellite news service Sky News, Dave Llewellyn, a ‘self taught chemist’, who until recently supplied mephedrone into the UK gave an insight into the legal highs pipeline.

‘The Chinese have been getting [naphyrone] ready for the last six months to take over the moment mephedrone was banned,’ he said. ‘It’s been ready – but why have two things banned at the same time? They want to keep the factories turning over chemicals.’

The authorities have another way of trying to stem the flow of new substances – whether legal highs, or illegal substances such as cocaine and heroin: they try to interrupt the supply of ‘precursor’ chemicals, which are the starting materials for controlled substances.

Under the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, there is a list of controlled substances – the so-called Red List. Many of these chemicals are used for legitimate purposes, but are also crucial for the production of illegal drugs.

Examples include safrole, a precursor of the insecticide piperonyl butoxide and MDMA; acetic anhydride, used in the production of aspirin and also for heroin; potassium permanganate, a strong oxidising agent, which can be used in MDA production; and piperonal, used in perfumes, but also an MDA precursor.

‘That listing is dynamic,’ says Treble. ‘If a new drug becomes a problem, then the precursor can be added to the list.’

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC) and the European Commission have also stepped up their efforts to stem the flow of precursor chemicals into South America and the Caribbean, by launching a three-year project called Prelac.

‘With the support and collaboration of chemical operators, Prelac will enhance the capacity of national control authorities and enable the target and seizure of diverted precursor chemicals,’ UNDOC states.

But, says Treble, this type of legislation is a ‘blunt instrument’, because there is more than one way to make a chemical substance.

‘There’s usually one easy way to market, so you ban that precursor,’ he says. ‘But you could then use a different synthesis route. People who are experts in synthetic chemistry can come up with several routes.’

While the chemical arms race continues, he says that the dangers of legal highs will become evident in time.

‘It’s a big uncontrolled human trial,’ he says. ‘These substances have never been evaluated in humans for their long term effects and there are real concerns about them.’

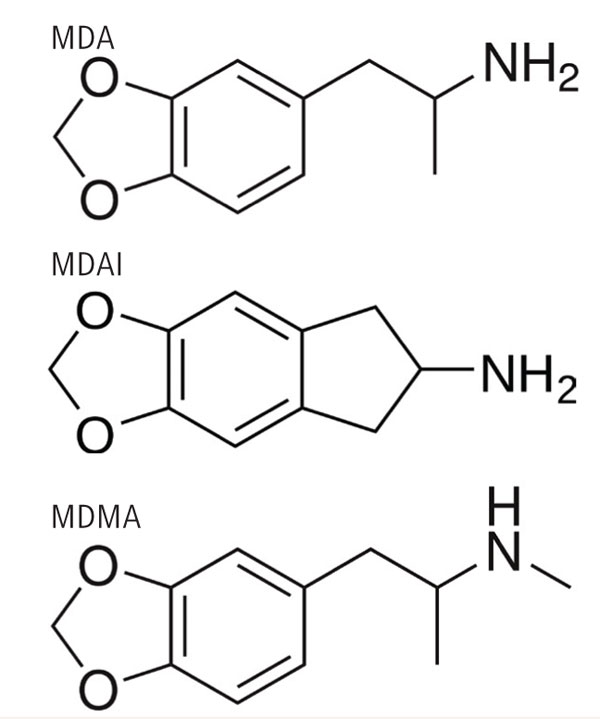

Spot the difference: similar structures, similar effects

A look at the chemical structures of MDA, MDMA (ecstasy) and MDAI (right), currently a legal high, shows how similar they are.

All three can be derived from safrole – an oily liquid derived from the bark and root of Sassafras plants. For this reason, safrole is a controlled precursor under the UN Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. The structure of piperonal is also remarkably similar.

Mephedrone and naphyrone (NRG-1) are also chemically similar. According to one former supplier of mephedrone, naphyrone has been waiting in the wings to hit the market as soon as mephedrone was banned.