The pharmaceutical industry is facing possibly its toughest ever challenge as analysts predict a marked slowdown in sales over the next few years, primarily due to the blockbuster patent cliff and impending generic competition. The latest figures for drug approvals in the US – just 21 new drugs approved last year – shows the scale of the problem industry has to deal with. With declining revenues, the industry needs to redefine itself – by improving R&D productivity, diversifying and, most importantly, innovating – if it is to survive.

With governments cutting or freezing health care budgets, the industry is facing an uphill struggle for sales over the next few years. In addition, health care reforms in the US and associated drug discounts are expected to cost the industry $119bn in lost revenue by 2019, says John Arrowsmith, scientific director in the Life Sciences Consulting business at Thomson Reuters.

The primary challenge facing the industry is the so-called patent cliff and the associated threat from generic competition. Arrowsmith points out that $76bn will be lost in worldwide revenues by the pharmaceutical industry between 2010 and 2014 due to dozens of drug patent expiries. These include the world’s largest selling products, such as Pfizer’s anti-cholesterol drug Lipitor ($11.7bn) and Lilly’s antipsychotic Zyprexa ($4bn) in 2011 followed by Bristol-Myers Squibb and sanofi-aventis’ blood thinner Plavix ($9.6bn) in 2012.

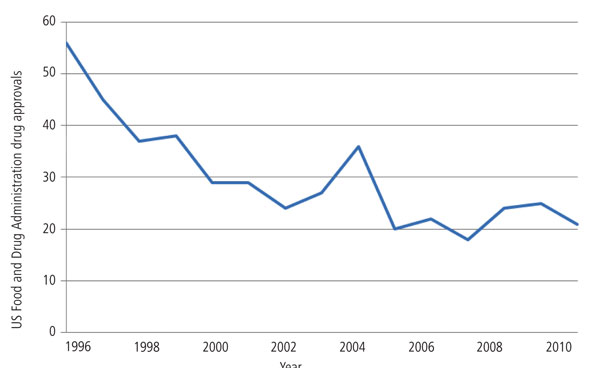

Readily replacing the revenues from patent expiries is unlikely, given the cost and difficulty of drug development: the cost of developing a new drug is higher than ever – about $1.3bn, according to the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD). Moreover, the approval of new drug applications (NDA) is falling – with just 21 brand new drugs, excluding vaccines, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2010 (see Figure 1).

The low approval of NDAs reflects increasingly stringent regulators. This is coupled with health care providers’ reluctance to pay for new drugs, particularly in key areas of unmet need, such as neurodegenerative disease, psychiatry and cancer, according to Thomson Reuters. And high-profile safety scares, such as those involving Merck’s painkiller Vioxx (C&I, 2004, 2, 6) and GlaxoSmithKline’s diabetes drug Avandia (C&I, 2007, 11, 11), have led to larger and more costly clinical trials.

‘The research-based drug industry, in the United States and globally, is not sitting still, but the question remains whether developers can bring enough new drugs to market at the pace needed to remain financially viable,’ says Tufts CSDD director Kenneth Kaitin.

In an effort to survive, pharmaceutical companies are trying to diversify, cut costs and innovate – key trends that are going to play out over the next few years, says Simon King, health care analyst at Datamonitor.

One strategy is to target emerging markets, where growth rates are impressive, in relation to established markets, and R&D is relatively cheap. Many large pharmaceutical firms have struck highprofile deals in BRIC and other countries. Abbott, for example, bought Piramel’s Healthcare Solutions last year, making it India’s number one pharmaceutical company (C&I, 2010, 11, 6).

In addition to expanding their reach into emerging markets, most companies will spread R&D risk by diversifying into biologics and vaccines, life cycle management and product enhancement, generics, consumer health, animal health, devices and diagnostics, says Arrowsmith.

Novartis is one of the few big pharmaceutical firms expected to generate above average growth over the next four years and has heavily diversified into biologics, antibodies, vaccines and diagnostics, in addition to its innovative small molecule pharmaceutical business. In January 2011, Novartis said it would acquire the diagnostic firm Genoptix for $470m to enhance its molecular diagnostics unit.

Actions that will help improve R&D productivity, according to Tufts CSDD, include greater reliance on translational science to help identify the right disease targets for new molecules; greater use of partnering with external service providers to share risks, reduce cycle times, lower costs and improve resource management; and greater use of sophisticated portfolio management techniques.

There has also already been significant restructuring of R&D in the industry to focus on areas of unmet need with significant commercial returns, such as oncology and Alzheimer’s, says King. He points out that there are few examples of small molecule products being the only driver for a company – Gilead’s HIV portfolio being an exception.

With the decline in sales over the next few years predicted to be primarily in the small molecules market, industry will be looking to invest more in products insulated from the generic threat, such as biologics and orphan drugs. Sanofi aventis, for example, has been pushing the purchase of biotech heavyweight Genzyme for some time.

In addition, ‘there has been a resurgence of activity in rare disease or stratified patient groups of more common diseases,’ says Arrowsmith. ‘This strategy reflects the higher likelihood of showing good efficacy outcomes in areas of high unmet medical need and so eases the path through the regulators and onto the market.’

However, while this is a successful formula it does raise some interesting marketing headaches for bigger companies, adds Arrowsmith. Blockbuster opportunities will emerge in areas like anti- coagulation and will be built through iteration, as seen in oncology, but will not be the sole focus for pharmaceutical companies, due to the high risk and price of this approach.

The other strategies employed by companies facing the patent cliff are not without their dangers too. While emerging markets have significant potential for achieving sales growth, this can only be expected over the medium- to long-term as a result of gradual investment.

In addition, although biologics and vaccines are enticing, not all companies will have or be able to acquire the necessary capabilities to migrate from small molecules.

Moreover, biologics and vaccines will have limited commercial benefit; the growth of therapeutic proteins is expected to slow by 2015 as the market matures and they start facing competition from biosimilars, which will enjoy significant growth over a decade, says King.

Industry is expected to continue cost cutting – reducing operating costs, particularly in sales. In addition, the overarching strategy of big M&As – such as Pfizer’s acquisition of Wyeth in 2009 and Merck & Co’s purchase of Schering-Plough also in 2009 – can be expected to continue to 2015 and beyond, says King (C&I, 2009, 3, 5; 6, 5).

However, although large scale M&As can help with cost cutting and diversification, there is still a question mark over its effect on innovation, especially in very large acquisitions. And it is innovation that is the key to circumventing the negative impact of generic erosion, says King. ‘It is arguably the only means of assuring long-term growth.’

Emma Dorey is a freelance writer based in Brighton, UK.

Generics hold both opportunities and dangers for Big Pharma

While the generics industry is set to immediately benefit from the patent cliff, it is the branded pharmaceutical companies that are likely to profit from the market for biosimilars over the next decade.

Health care providers are expected to switch patients to cheaper generic versions as soon as they available. ‘If the current rate of generic substitution is maintained, first-time generic entry occurring through 2012 will generate about $14bn in additional US Medicare savings from generic substitution, in addition to the $33bn already achieved from 2007,’ says John Arrowsmith at Thomson Reuters.

In addition, with 12 years market exclusivity defined in the regulatory path for copycat versions of biological drugs (biosimilars/biogenerics), there will be further savings from the highest cost therapies, says Arrowsmith.

However, in the coming years fewer small molecule opportunities and the inability to produce biologics, may squeeze out many generics companies. But having evolved or acquired the ability to develop biosimilars, many Big Pharma and biopharma companies – previously not generic players – will be able enter and dominate the generics sector.

Merck BioVentures is one company pursuing this strategy and formed a strategic alliance with Parexel in January 2011 to develop biosimilar candidates.