Economics expert Paul Hodges gives his views on the business outlook for the chemicals sector in 2022 and beyond as the world settles into the ‘new normal’ of the Covid era

Q How has Covid affected the economic outlook for chemicals here in the UK and globally?

The main impact has been to introduce major uncertainty into the outlook, and hence the forecasting process for demand. Until 2020, for example, different end-user segments tended to all move in roughly the same direction. But with lockdowns, demand for home furnishings, electronics and plastics packaging for home delivery all soared, whilst demand into the travel and hospitality sectors collapsed. Coming out of the first lockdown, demand began to rebalance – but then more lockdowns came along to cause further confusion – amplified by the temporary furlough payments, which only supported demand in certain areas.

At same time, the pandemic has also accelerated paradigm shifts such as concern over climate change, whilst the surge in online ordering during lockdowns has sensitised people to the scale of the waste plastic issue.

- There was also the international dimension in terms of the impact on supply chains.

- China’s vast shipments of PPE equipment meant a lot of containers went on a one-way journey and have never returned. So, when demand began to recover last year, as the vaccination programmes got under way, the container shortage became very obvious and container freight rates rose 10-fold or more in H2 2021.

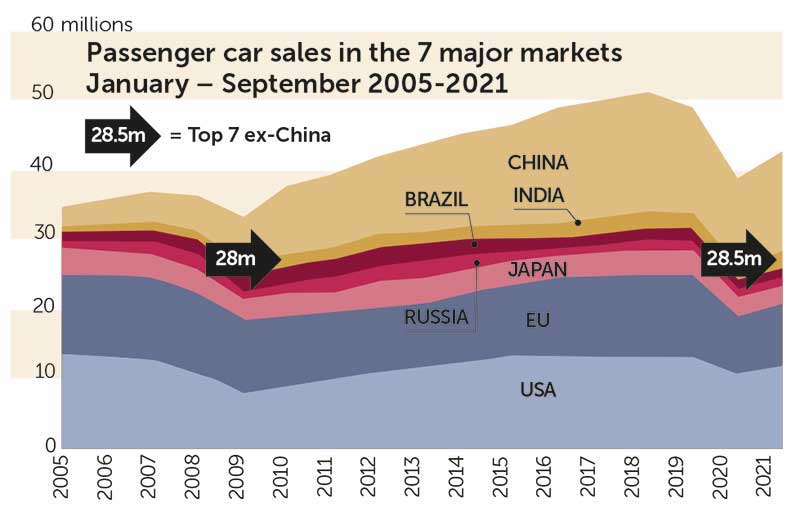

At the same time, companies began to reorder important components such as semi-conductors. But, of course, these normally operate on six-month lead-times. And unfortunately, the car industry (one of our key customers), has been very badly impacted by this shortage, with most companies reporting production cutbacks as a result.

So where are we today? It seems almost certain that we will continue to see major uncertainty during 2022, with companies needing to develop scenario analysis in order to identify the different outcomes they might face.

It seems reasonable to hope that 80%+ of the Western European population will be vaccinated by the end of Q1 2022, allowing countries to reopen their economies on a sustained basis. But unfortunately, health policy has become politicised. And so, one suspects that different countries and regions will continue to adopt different policies:

- Some will have complete vaccination along with long-term precautionary measures such as vaccine passports.

- Some will have vaccination but won’t maintain these precautionary measures.

- And some, particularly in Asia, will likely continue with ‘Zero-Covid’ policies. China, for example, has virtually closed its border to travel, and routinely shuts down vast cities like Xi’an and Tianjin, as well as major ports, when just a few Covid cases are reported.

These different approaches will make it very difficult to operate global supply chains. So, we would expect to see more and more focus on reshoring supply chains. Essentially, this makes it likely markets will return to being more local and regional over time.

The ‘top 7’ auto market sales are down 13% versus 2019. Source: New Normal Analysis, National Auto Manufacturer Organisations

Q How do you see demand patterns evolving?

It seems more and more doubtful that demand will return to pre-pandemic patterns, due to the behavioural changes that have taken place. It seems unlikely, for example, that people will travel as much as they used to, pre-Covid.

- In the business world, working from home has become much more acceptable. And Teams/Zoom meetings are now routinely being used throughout the industry.

- Equally, in their personal lives, people have become much more cautious as a result of the pandemic. It seems likely that we are entering a New Normal in many areas of demand.

Nor can we ignore the impact of the pandemic on the Net Zero issue and the sustainability agenda. Net Zero is now being widely adopted by chemical companies and their customers in the UK and overseas. And as the Deputy Mayor of Milan noted early on in the pandemic, this means that plans being made for 2030 are now moving forward today.

- Plastic waste is one obvious example. The recycling debate has clearly been turbocharged during lockdowns. People have seen the volume of waste piling up in their homes, as they were forced to order online. So, 2022 may well see an international Treaty agreed on the subject, which will further accelerate rapid change.

Q How is the move to electric vehicles (EVs) likely to affect the chemicals sector – both in terms of feedstocks and chemical demand?

EVs are another area where change is accelerating. Battery vehicles (BEVs) took a 25.5% market share in the UK in December 2022. And for the sixth month in a row, more BEVs were sold than diesel cars. The issue is that transformations take place on an S-curve, rather than in a straight line. And with the UK government mandating the end of diesel and gasoline sales by 2030, it seems likely that sales will continue to accelerate. In turn, of course, this will pressure the UK’s remaining refineries, and those across Europe, due to lack of demand for their core products. This naturally creates a major challenge for the chemical industry, given our current dependence on naphtha as a feedstock.

At the same time, of course, the demand for recycled plastic is also increasing, with the UK Plastics Pact mirroring EU policy in calling for 30% average recycled content across all plastic packaging by 2025. We are therefore being squeezed from both ends of the value chain. Upstream, we are set to lose our core feedstocks as refineries close. Downstream, we will lose core markets as brand owners and retailers move to use recycled plastics instead of virgin product.

So, there is an urgent need to turn this challenge into an opportunity by moving to adopt chemical recycling technologies at scale.

Q What trends are driving increased localisation and reshoring of chemicals production? How fast is this occurring?

A number of key factors are driving this development. One is the result of the pandemic-related changes described earlier. A second is due to the demographic changes now under way in the UK and the Western world.

Today’s global supply chains began to be established in the 1980s-1990s, when the Baby Boomers born between 1946 and 1970 were moving into their peak buying period. For example, the UK saw a 20% population increase between 1946 and 2000, according to ONS data. So as an industry, our major focus was simply on obtaining as much ‘stuff’ as possible from potential new supply sources like Asia.

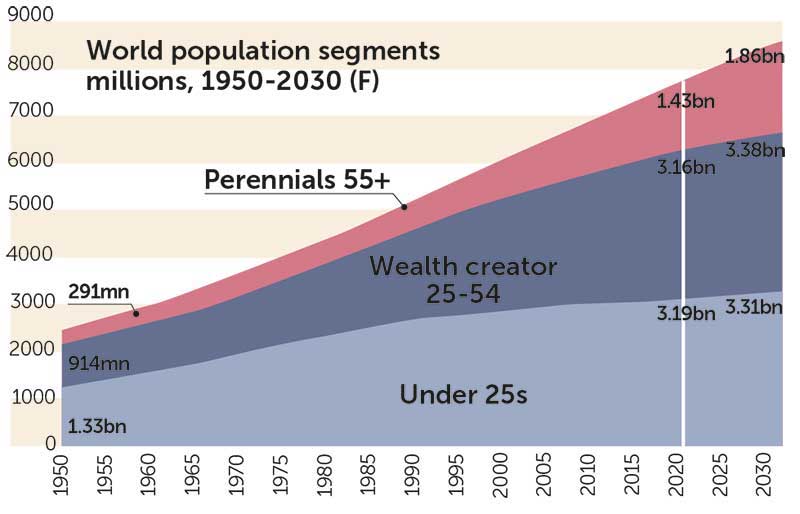

Fast-forward to today, and we have the opposite issue. Life expectancy has increased by around 15 years since 1946, but fertility rates in the UK and most of the West have been declining. They have been below the replacement level of 2.1 babies/woman for the past 50 years. So, we have an ageing population.

Essentially, therefore, today’s challenge is not to provide more ‘stuff’. Instead, it is ‘to do more with less’. Sustainability is replacing globalisation as the key driver for the UK chemical industry. In turn, of course, this supports the need to move to a more local and circular economy.

Q How are ageing populations affecting expenditure and chemicals demand?

We have excellent data from the UK Office of National Statistics on this area, which show that demand reduces as populations age. The Wealth Creators in the 25-54 age range create a lot of demand as they settle down, have children, and earn more money as they move ahead in their careers. But the Perennials in the 55+ bracket already own most of what they need, and their incomes decline as they go into retirement. So, we need to think more about providing services than molecules – which means there is a great opportunity for us to leverage our engineering and business skills to become a more service-oriented industry.

A completely new generation has developed since 1950. The perennials 55+ are >50% of world population growth to 2030. Source pH report, UN Population Division

Q What are your own opinions on central bank policies? What should they be doing in your view?

I think the short answer is that the Bank of England, and other central banks, have caused an immense amount of disruption. They fell into the trap of thinking that something as complex as a national or global economy could be run by monetary policies. Print more money, generate more demand.

Wouldn’t it be lovely if life was really that simple, and we didn’t have to ever worry about debt and bankruptcy?

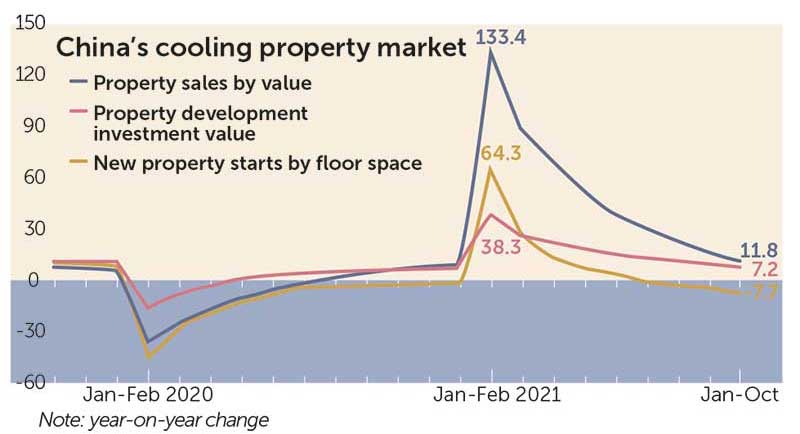

Even worse, their key focus for monetary policy was on boosting asset prices – pushing up stock markets and house prices. And so, they have pushed these to unsustainable levels, by effectively destroying the key role of markets, price discovery. If the price went up, we were simply told to borrow more, to ‘keep the economy moving’. Now, we are going to see the downside of this folly, as markets rediscover their key role and asset prices return to more rational levels. I fear this means we may some difficult few years ahead, whilst their mistakes are corrected.

China’s real estate bubble is bursting. Source: National Bureau of Statistics, iFinD

Q What are your thoughts on future US and UK GDP growth forecasts?

Forecasters are generally being far too optimistic about the outlook for the UK and global economy.

We have been effectively on a ‘sugar-high’ since 2009, due to the amount of stimulus supplied by the central banks – $23tn from the Western banks, and double that from China. But the asset bubbles they have created are like balloons. They need more and more ‘air’, in the form of money-printing to keep them from deflating. And now that support is being withdrawn.

We can see this happening in the chemical industry, well-known to be the best leading indicator for the global economy. Industry pricing data warned a year ago that inflation was set to rise. And now it is warning that demand destruction should be our key concern – due to the inflation generated by energy prices and the supply chain disruptions. People only have a certain amount of cash to spend, and if they spend more on food, transport and keeping warm, then they have less to spend on more discretionary areas that drive economic growth.

Energy woes

Q How are chemicals companies faring in terms of energy costs, particularly here in the UK? Are high UK costs making the UK less competitive? Again, what factors are driving up energy prices and how much higher can we expect to see these climb?

We could talk all day about the short-sightedness of UK energy policy. The UK government refused to fund the necessary updating of the Rough gas storage facility in 2017. This means that the UK now only has around 10 days strategic storage, compared with 40-50 days on the continent.

A further problem has been that ministers haven’t thought through the details of the transformation needed to run the UK’s energy system on the basis of renewables. They were very happy doing photo-ops with windmills and solar panels. But they didn’t get around to planning for the need to organise and finance back-up supplies. The issue is that one needs to provide storage capacity via batteries and other technologies for when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine.

Renewables have the potential to provide very cheap energy for much of the time. And although need for back-up storage means the costs will be higher on windless, dark days in winter, the corollary is that one isn’t vulnerable to the geo-politics we suffer from today in oil and gas markets. Brexit, of course, doesn’t help either. The best solution would be for the UK to develop coordinated policies with its EU neighbours to pool costs and supplies. But instead the government has preferred to stress its ‘global Britain’ focus. But there isn’t much that Australia or India can do to help us in the energy field. And so costs are likely to be higher, and supply reliability lower.

Q Are energy companies deliberately withholding supply – and what are the potential long-term consequences of that behaviour?

As the IEA reported in May 2021, we are entering the end-game for fossil fuels. No further investment is needed in this area if governments really want to achieve Net Zero targets. So, one shouldn’t be too surprised that the producers have been busy ramping up their prices as fast as possible, to maximise their profits whilst they still can. OPEC+ originally introduced their quotas as a short-term emergency measure in Q2 2020, but they have instead now become a profit-maximising policy. The same is true for Russia with its gas supplies. Of course, in the longer-term, their strategy will accelerate the adoption of renewables. But that is not their concern today.

Paul Hodges is chairman of New Normal Consulting, a Swiss-based strategy consultancy advising chemical companies and investors on areas where we have long-term expertise.

Image credit: I. NOYAN YILMAZ/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY