In ‘The Flowers that Bloom in the Spring’ from The Mikado, Gilbert and Sullivan were interpreting the seasons according to their 19th Century climate – but do these flowers still, indeed, bloom in spring? The Meteorological Office’s traditional definitions of the seasons in the UK are:

- Summer from June to August

- Autumn from September to November

- Winter from December to February

- Spring from March to May

Increasingly, climate change is blurring these distinctions, and gardeners are seeing autumn stretching well towards January. Winters in maritime Great Britain are now most severe in February and March, and summer extends into September. The effects of prolonged warm autumns include accelerated growth emergence and flowering of plants which have been thought of as the harbingers of spring.

Phenological studies in the late 20th and early 21st Centuries established that the then-termed ‘early-spring flowering plants’ had accelerated blossoming by as much as four weeks. Now, in the second decade of the 21st Century, it seems this is an underestimate.

Pictured above: Iris unguicularis (styllosa); the Algerian iris

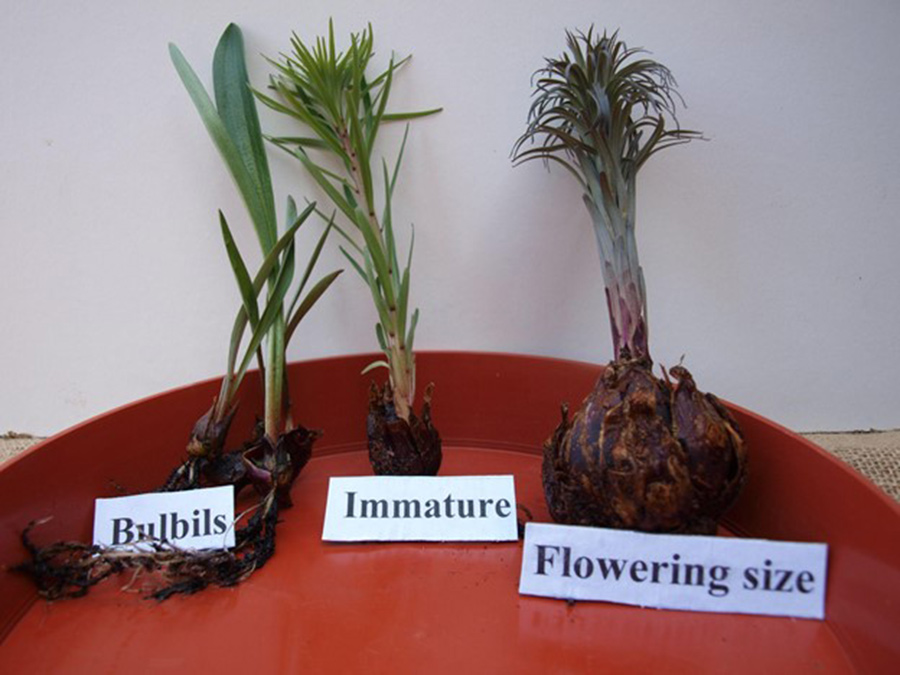

Iris unguicularis (styllosa), the Algerian iris, is renowned as an early flower of spring. It now comes into bloom in late November and very early December, making it an autumn and winter flowering plant. It originates from Algeria, Greece, Turkey, Western Syria, and Tunisia and requires freely draining, light soils with minimal nutrient value. Planted in a south facing border, Iris unguicularis is an undemanding and very colourful addition to the garden. Many early-flowering plants have highly coloured flowers which attract the widest spectrum of insect pollinators.

Pictured above: Cyclamen hederifolium

Similarly, Cyclamen hederifolium (hera meaning “ivy”, folium meaning “leaf”), now flowers vigorously from mid-December, providing colour in the garden in those darkest days prior to the winter solstice. It originates from woodland, shrubland, and rocky areas in the Mediterranean region from southern France to western Turkey and on Mediterranean islands. Once the corms are established it naturalises freely, spreading by self-seeding from explosive seed capsules which cast progeny widely in borders of light, sandy nutrient-free soil.

Pictured above: alyssum (A. saxatile)

The common rockery plant alyssum (A. saxatile), is a perennial herbaceous plant, which rapidly colonises borders and will spread down onto walls providing colour from early January. It is one of the ornamental members of the cabbage family (Brassicaceae) with bright cruciform flowers.

Each of these plants is responding to climatic warming, indicating the loss of traditional seasonality. This impairs relationships between flowering plants and animal pollinators that have carefully evolved for mutual benefit over millennia. The full consequences of these losses will be apparent in years and decades to come.

Professor Geoff Dixon is author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Composts are artificial mixtures in which seeds germinate, cuttings root and whole plants grow. Their key feature is reliability of composition. The first such composts were formulated by the John Innes Centre in the 1900s. Researchers needed preparations which allowed reliable growth of plants for experiments. The main ingredients were loamy soil, sand and lime plus nutrients. John Innes composts subsequently became the mainstay of horticulturists and gardeners.

Colourful flowering in artificial composts.

Variability in the loam and its weight were major disadvantages. Scientists at the University of California solved these problems by preparing mixtures of peat, sand and nutrients. Air fill porosity characteristics of ‘UC mixes’, as they became known, allow healthy seed germination, root production, growth and flowering. Lighter weight is of major significance, allowing the easy movement of plants. Arguably, simplified transport also resulted in the advent of garden centres and freer international plant trading. As a result, the garden centre industry has become a regular social feature.

A peat extraction site.

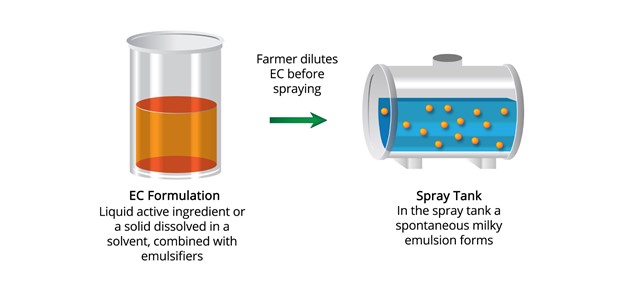

Peat, while of major importance, is now seen as the ‘achilles heel’ of these composts. Peat bogs are very significant reservoirs for carbon dioxide and major participants in the drive for reducing the impact of climate change. The compost industry strips peat from the bogs and then mixes it into specialised formulations for seed germination or plant growth. The bogs can be reclaimed and will restart the processes of CO2 absorption, but there is still a significant environmental penalty. Social and political pressures are driving peat reduction and its elimination from garden and commercially used composts. Peat substitutes must have the key properties of adequate air fill porosity, light weight and minimal or net zero carbon demand.

A renovated peat extraction site.

One suggestion is using coir – waste arising from coconut harvesting. Like peat, this is a natural, biodegradable product. When shredded it forms a useful peat substitute, an alternative is well composted bark and fine wood chippings, which are mixed with sand. Both are valuable composts for growing ornamental plants and germinating their seedlings. Some manufacturers are also adding loamy soil into these formulae. Problems continue, however, with finding peat-free formulae for use in commercial transplant propagation. Germinating vegetable seedlings for large scale crops requires absolute regularity and reliability. Uniform, vigorous seedlings result in mature high-quality crops suitable for once over harvesting and scheduling which meets supermarkets’ specifications.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

As we speak, apples and pears are ripening on the trees. But how do you grow apple and pear trees from scratch and keep them alive? Our resident gardening expert, Professor Geoff Dixon, investigates.

Autumn is the ‘season of mists and mellow fruitfulness’, as John Keats said in his Ode to Autumn. It is a time for harvesting temperate tree fruits, especially apples and pears in gardens and orchards.

This fruit is distinctive and delicious. The ‘Sunset’ apple cultivar, derived from the Cox’s Orange Pippin, produces red and gold striped fruit and sweet tasting flesh, while the French pear cultivar doyenne du comice has the most superb taste if caught at peak ripeness.

<

<

The sunset apple.

Both apples and pears ripen after harvesting, emitting ethylene and passing through a climacteric, or critical biological stage. When respiration reaches a peak, the fruits’ flavour is most satisfying.

Both apples and pears are best planted in late autumn or during winter when the trees are dormant, either as container-grown or preferably bare root trees. Place each tree in a hole that is large enough for the entire root system, ensuring that the graft union sits well above the soil level.

Each tree consists of two parts: the rootstock, selected originally from wild species, and the scion, which is the fruiting cultivar. Apple cultivars mostly dwarf Malling no. 9, and pear scions are grafted onto quince rootstocks. A stake should be driven into the hole before putting the tree in place.

Pour ample water into the hole, keeping the roots wet. Do so again once soil is replaced and firmed round the tree. As the tree establishes and produces leaves and flowers, water well and regularly, especially during dry periods.

French pear cultivar doyenne du comice

Feed with fertilisers that contain large amounts of potash and phosphate but minimal nitrogen. This encourages vigorous root growth. Sprinkling compost or farmyard manure around the tree helps retain soil moisture.

Climate change is having significant deleterious impacts on all members of the Rosaceae family, including apples and pears. Australian studies indicate that temperatures are reaching higher than the evolutionary maximum for these species.

This stresses the plants. It adversely affects their health and performance and reduces their ability to store carbon and produce fruit crops.

The pear scab Venturia pirina

Levels of pest and disease infections are increasing. In particular, sap-sucking woolly aphids (Eriosoma lanigerum) have increased from minor to major apple pests in the last decade. Pear scab Venturia pirina has become a major cause of defoliation.

Chemical control options for both are limited, but regular drenching sprays with seaweed extracts may reduce their impact. Seaweed extracts additionally provide some foliar absorbed nutrients and increase the visual quality of fruit.

Professor Geoff Dixon is author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Which species can you plant to increase the nutrients in your soil and boost biodiversity, and which pathogen tackles some of those pesky weeds? Our resident gardening expert, Professor Geoff Dixon, tells us more.

The term ‘sustainability’ for gardening means replacing what you take out of the soil and supporting localised biodiversity. Harvested crops, for example, take out nutrients and water from the soil. Replacements should be supplied that aid biodiversity and have minimal impact, or zero impact, on climate change.

Seaweed (Ascophyllum) has been recognised as a valuable fertiliser source in British coastal areas for centuries. Now, proprietary seaweed extracts are gaining popularity either when applied directly as liquid feeds or sprays, or when added into composts.

Classed as biostimulants, seaweed extracts contain several micro-nutrients and a range of valuable plant stimulatory growth regulators. They encourage pest and disease tolerance, increase frost tolerance, stimulate germination, increase robust growth, and add polish to fruit such as apples and pears.

Seaweed bolsters some of the nutrients lost through gardening. Image from Geoff Dixon.

Benefits of borage

Some plants are very effective supporters of biodiversity. Borage (Borago officinalis), known also as starflower or bugloss, is a robust annual plant of Mediterranean origin with pollinator-attractive blue flowers.

It is very drought resistant and suitable for dry gardens. Although an annual, it is self-seeding and could spread widely. It is very attractive to bees as it produces copious light – and delicately flavoured honey.

Its flowers and foliage are edible with a cucumber-like flavour, making it suitable in salads and as garnishes, while in Germany it is served as grűne soße (green sauce). When used as a companion plant for crops such as legumes or brassicas, it will also help to suppress weeds.

Borage is good for bee and belly. Image from Geoff Dixon.

Weeding out the problem

Weeds are a continuous problem for gardeners and their prevalence varies with the seasons. Groundsel (Senecio vulgaris), also known as ‘old man in the spring’, persists whatever the weather.

It is ephemeral but can seed and regrow several times per year. As a result, once established, it is difficult to control without very diligent hand weeding and hoeing out young seedlings before the flowers form.

There is, however, a form of biological control that can aid the gardener. Groundsel is susceptible to the fungal rust pathogen (Puccinia lagenophorae). This pathogen arrived in Great Britain from Australia in the early 1960s. Since then, it has become well established and outbreaks on groundsel start to become obvious in mid- to late-summer, especially in warm dry periods.

A fungal pathogen can kill groundsel, a weed that comes through several times a year. Image from Geoff Dixon.

Severe infections weaken, and eventually kill, groundsel plants. Gardeners should take advantage of the infection and remove the diseased weeds before any seeds are produced.

>> How else has climate change changed the way our gardens grow, and what can be done to alleviate its effects? Geoff Dixon investigates.

Professor Geoff Dixon is author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon. You can find more of his work here.

The Commonwealth Games has landed in Birmingham. Before the Games began, viewers were treated to an extraordinary opening ceremony (featuring a giant mechanical bull) and its artistic director, Iqbal Khan, was lauded for his ingenuity.

But such ingenuity shouldn’t surprise any of us, for Birmingham has long been a place of outsized invention. For more than 300 years, the inhabitants of this industrial powerhouse have churned out invention after invention; and its great pragmatists have turned patents into products.

Chemistry, too, owes a debt to the UK’s second city. Whether it’s the first synthesis of vitamin C, the invention of human-made plastic, adventures in mass spectrometry, or electroplated gold and silver trinkets, Birmingham has left a lasting legacy.

Here are five chemists whose innovations may have made an appearance in your life.

Alexander Parkes – man of plastic

Plaque commemorating Alexander Parkes in Birmingham, England. Image by Oosoom

Look around you. Look at the computer screen, the mouse button you click, and the wire casings everywhere. Someone started it all. That man was Alexander Parkes, inventor of the first human-made plastic.

The son of a brass lock manufacturer from Suffolk Street, Birmingham, Parkes created 66 patents in his lifetime including a process for electroplating delicate works of art. However, none were as influential as the 1856 patent for Parkesine – the world’s first thermoplastic.

Parkes’ celluloid was based on nitrocellulose that had been treated by different solvents. In 1866, he set up the Parkesine Company at Hackney Wick, London, but it floundered due to high cost and quality issues. The spoils of his genius would be enjoyed by the rest of us instead.

Sir Norman Haworth – the vitamin seer

Sir Norman Haworth

Sir Norman Haworth may have been born in Chorley, Lancashire, but his finest work arguably came after he became Director of the Department of Chemistry in the University of Birmingham in 1925. Haworth is famous for his groundbreaking carbohydrate investigations and for being the first to synthesise vitamin C.

By 1928, Haworth had confirmed the structures of maltose, cellobiose, lactose, and the glucoside ring structure of normal sugars, among other structures. Apparently, his method for determining the chain length in methylated polysaccharides also helped confirm the basic features of starch, cellulose, and glycogen molecules.

However, Haworth is most famous for determining the structure of vitamin C and for becoming the first to synthesise it in 1932. The synthesis of what he called ascorbic acid made the commercial production of vitamin C far cheaper – the benefits of which have been felt by millions of us.

For his achievements in carbohydrates and vitamin C, Haworth received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1937 (shared with Paul Karrer). He was the first British organic chemist from the UK to receive this honour. Haworth even had a link to SCI, having been a pupil of William Henry Perkin Junior in the University of Manchester’s Chemistry Department.

Francis William Aston – adventures in mass spectrometry

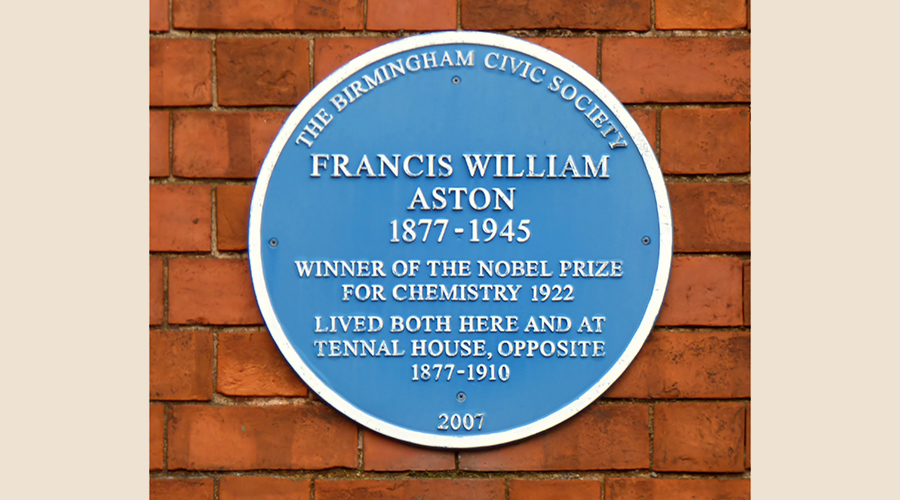

Blue plaque for Francis William Aston. Image from Tony Hisgett

Another Nobel Prize-winning chemist from Birmingham is Francis William Aston. The Harborne native won the 1922 prize for discovering isotopes in many non-radioactive elements (using his mass spectrograph) and for enunciating the whole number rule.

For a time, academia almost lost Aston, as he spent three years working as a chemist for a brewery. Thankfully, he returned to academic life and obtained concrete evidence for the existence of two isotopes of the inert gas neon before the first World War.

After working for the Royal Aircraft Establishment during the Great War (1914-18), he resumed his studies. The invention of the mass spectrograph proved pivotal to his discoveries thereafter. Using this apparatus, he identified 212 naturally occurring isotopes.

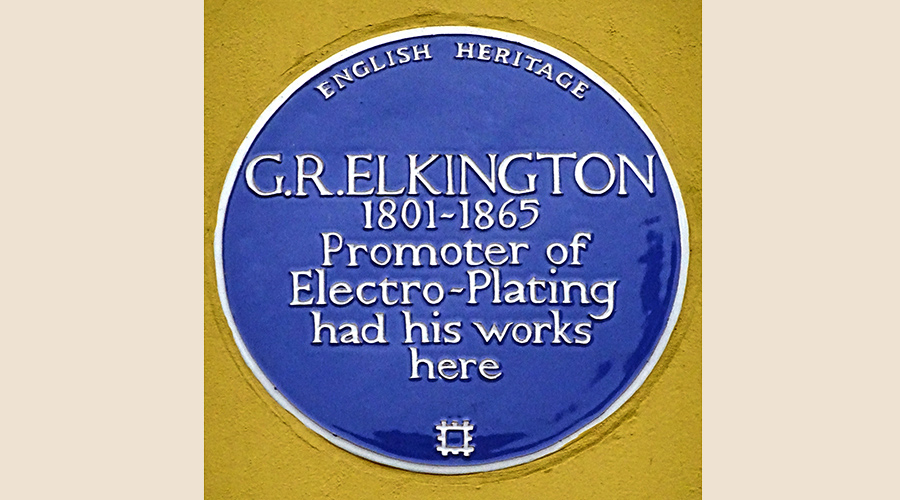

George Elkington and John Wright – all that glitters

George Elkington patented the electroplating process developed by John Wright. Image from Spudgun67

It isn’t surprising that George Elkington should become an SCI favourite, as he blended both scientific ingenuity with business. The son of a spectacle manufacturer patented the first commercial electroplating process invented by Brummie surgeon John Wright in 1840.

Wright discovered that a solution of silver in potassium cyanide was useful for electroplating metals. Elkington and his cousin Henry purchased and patented Wright’s process before using it to improve gold and silver plating.

The Elkingtons opened an electroplating works in the city’s now famous Jewellery Quarter where they electroplated cutlery and jewellery. And they didn’t do too badly out of it. By 1880, the company employed 1,000 people in seven factories.

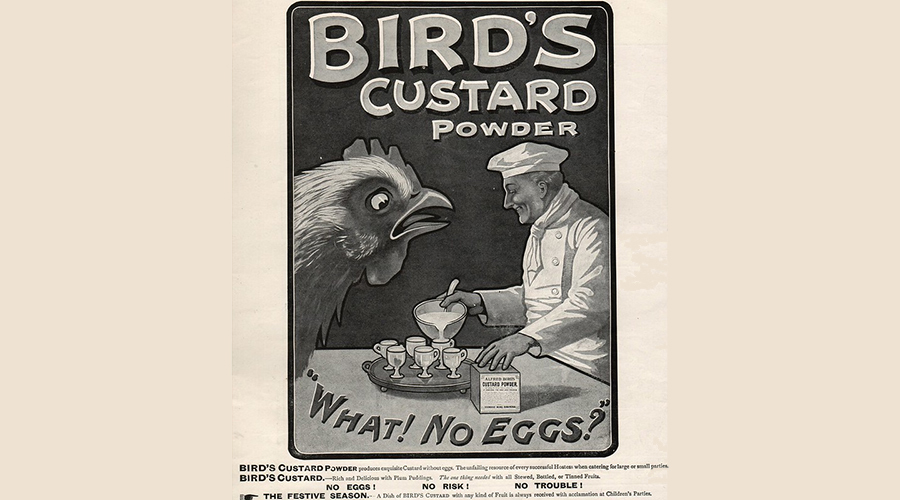

Alfred Bird – winging it

1906 advertisement for Birds Custard powder. Image from janwillemsen

In 1837, Alfred Bird was in a pickle. He wanted to serve his dinner party guests custard, but his wife was allergic to eggs and yeast, and egg was the main thickening agent of this delicious gloop.

Instead of serving something else, the chemist shop owner invented his own egg-free custard by substituting cornflour for eggs. His guests found it delicious and Bird’s Custard was born.

Not content with this innovation, Bird is also credited with being the father of modern baking powder. Once again, his wife’s allergies were said to be the inspiration, as he wanted to create a yeast-free bread for her. In bread and custard, true love always finds a way.

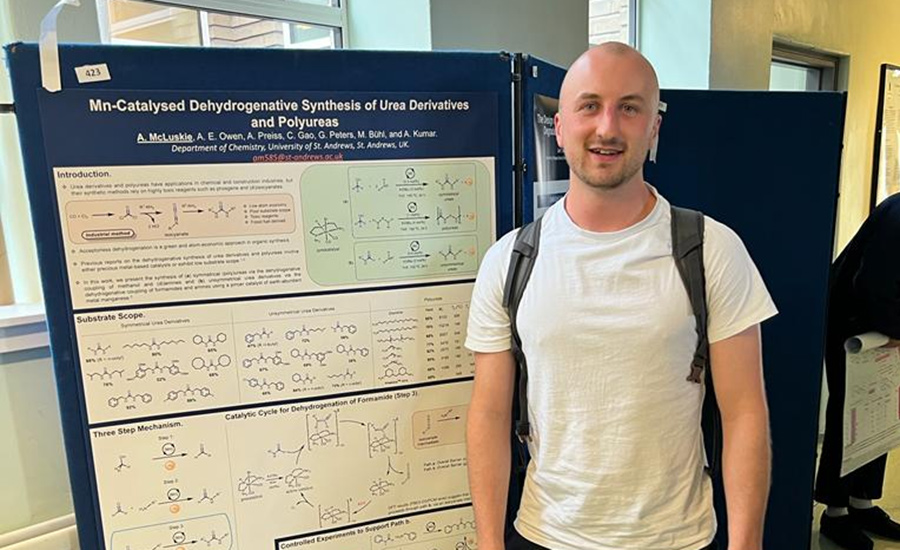

In his winning essay in SCI Scotland’s Postgraduate Researcher competition, Angus McLuskie, Postgraduate Researcher at the University of St Andrews, explains his work in replacing non-renewable and toxic feedstocks with novel sustainable catalytic processes to produce useful chemicals.

Each year, SCI’s Scotland Regional Group runs the Scotland Postgraduate Researcher Competition to celebrate the work of research students working in scientific research in Scottish universities.

This year, four students produced outstanding essays in which they describe their research projects and the need for them. In the first of this year’s winning essays, Angus McLuskie outlines his work in improving the production of urea derivatives and polyureas.

Would you risk your life for plastics and agrochemicals? You might not have to…

Urea derivatives hold a substantial global market, which is dominated by their use as fertilisers in the agrochemical sector, in addition to smaller-scale technical applications as glues, resin precursors, dyes and pharmaceutical drugs. Furthermore, polyureas are important protective coatings, with a global market exceeding £800 million a year.

Currently, urea derivatives and polyureas are produced on an industrial scale using highly toxic chemicals such as phosgene, (di)isocyanates and carbon monoxide. These reagents are detrimental to human health, as evidenced by the release of methyl isocyanate gas from the Bhopal Union Carbide factory in 1984, which led to thousands of deaths and a global outcry.

Phosgene was itself used as a battlefield chemical weapon in World War I, and is sourced from fossil-fuel-derived carbon monoxide. The result is a process with significant health and environmental impacts.

As part of a global drive to tackle climate change and move towards a circular economy, the objective of our research is to replace non-renewable and toxic feedstocks with novel sustainable catalytic processes to produce useful chemicals and materials.

>> More information about the Scottish Postgraduate Researcher competition.

In pursuit of greener methods, we have recently discovered synthetic methodologies, using a catalyst of manganese, to couple dehydrogenatively (1) methanol and (di)amines and (2) formamides and amines to make symmetrical (poly)ureas and unsymmetrical urea derivatives respectively (ACS Catal., DOI:10.1021/acscatal.2c00850).

Angus with his poster on Mn-Catalysed Dehydrogenative Synthesis of Urea Derivatives and Polyureas.

The only process byproduct, molecular hydrogen, is valuable in itself, and the non-toxic reagents of methanol or formamide can be sourced from renewable feedstocks. For example, Carbon Recycling International, an Iceland-based company, has developed methods to generate methanol industrially through the direct hydrogenation of CO2 (ATZextra Worldw., DOI:10.1007/S40111-015-0517-0). Formamides can be made from formic acid, which may be produced from biomass or CO2.

Synthesis approach

The synthesis of urea derivatives using this approach has been reported previously using iron and ruthenium catalysts, but these present individual limitations. Iron catalysts result in poor yields and substrate scope, while ruthenium catalysts are expensive and raise sustainability concerns due to ruthenium’s low abundance in Earth’s crust (Chem. Sci. J., doi.org/10.1039/C8SC00775F and Org. Lett., doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03328).

The synthesis of polyureas via this approach has only been achieved before using a ruthenium catalyst. With a manganese-based pincer catalyst, we succeeded in making a broad variety of symmetrical and unsymmetrical urea derivatives as well as polyureas at high yields and under a low catalytic loading of 0.5-1 mol%. As the third most abundant transition metal in Earth’s crust, manganese is much cheaper than ruthenium, which improves the economic viability of the process for industrial applications.

Breaking new ground?

This is the first example of the synthesis of polyureas from diamines and methanol using a catalyst of an Earth-abundant metal. We have demonstrated for the first time the synthesis of a potentially 100% renewable polyurea from methanol and a renewable diamine Priamine, which is commercialised by Croda. This could be of interest to emerging businesses for making bio/renewable plastics.

Angus hopes his research will help us develop urea-functionalised agrochemicals and pharmaceutical drugs in a more efficient, greener way.

This initial proof of concept is exciting, but there are challenges to overcome for commercialisation. Evidently, the cost is important, and since the catalyst is much more expensive than reactants, such as amines and methanol, the cost is directly linked to the catalyst’s activity; a homogeneous catalyst that is non-recyclable and offers a turnover number of 100-200 makes the process expensive.

We are now focusing our efforts on enhancing the efficiency of the catalyst to increase cost-effectiveness, which will also allow us to make commercially important urea-functionalised pharmaceutical drugs and agrochemicals with greater efficiency and reduced impact on the environment, human health, and economy.

The wild weather fluctuations wrought by climate change are stressing out our plants. Our resident gardening expert, Professor Geoff Dixon, explains how.

Pests and diseases are familiar causes of plant damage and loss. Less familiar, but becoming more frequent, are stresses resulting from environmental causes.

These are termed abiotic stresses because no living organism is involved. This means there are no visible signs of pests or pathogens. Diagnosis and treatment are, therefore, less straightforward. These causes are a result of interactions between the plant genotype and the prevailing or changing environment.

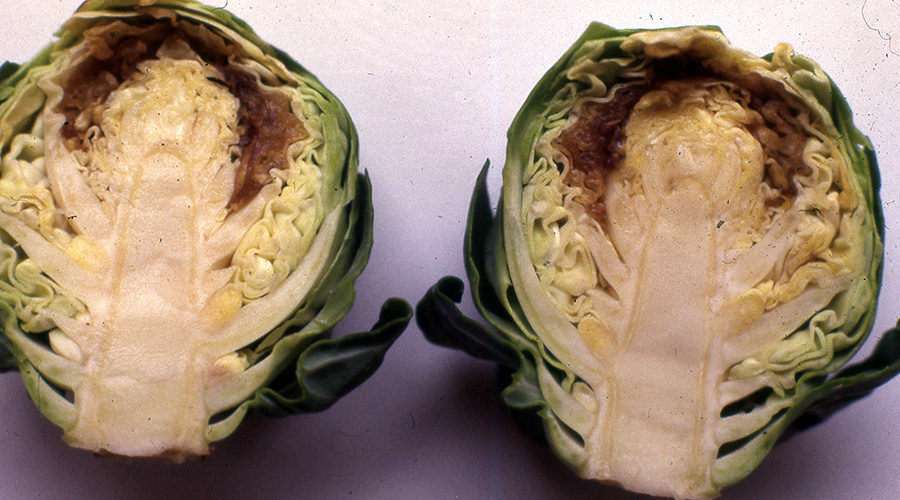

Damage may only become apparent after harvesting and at the point of consumer use. A typical example of this is internal browning or breakdown of Brussels sprouts. Larger sprouts are more susceptible to stress, with dense leaf packing in the bud, particularly in early and midseason cultivars.

The internal browning of Brussels sprouts is a consequence of plant stress.

A suggested cause is water condensing within the bud, which restricts calcium transport and leads to marginal leaf necrosis (death). This resembles the exudation, or perspiration, of water from leaf edges when growing plants absorb excessive water, flooding the vascular systems following very heavy rainfall and hot weather.

Moisture damage

Oedema is another moisture-induced disorder. Symptoms include unattractive wart-like swellings coalescing on leaves and stems, particularly on Brussels sprouts, cabbages, and cauliflowers. These may rupture, becoming corky with a yellowish or brownish appearance.

Moisture-induced damage to cabbage leaves.

These symptoms result from high soil moisture content and high relative humidity associated with hot days and cool nights. Both internal browning and oedema can be minimised by improving soil structure, encouraging rapid drainage by deep cultivation or growing plants on raised beds.

Improving soil structure is becoming an important way to control salt accumulation. Soil structure can be badly damaged by flooding that brings in polluted water. In subsequent vegetable and fruit crops, plant water uptake, nutrient use efficiency, and photosynthesis are all impaired. The effects are seen in poor germination, burnt leaf margin, stunting, and wilting. This damage will be particularly severe with highly organic soils.

Salt accumulation in onion crops. Improving soil structure is one way of addressing this problem.

Abiotic disorders are becoming more common in commercial crops and this is likely to be reflected in gardens and allotments. That is an effect of climatic change, with generally hotter and wetter conditions interspersed by droughts and freezing events.

As a result, plant growth is erratic and exhibits abiotic disorders. Plant breeders, especially in Asia, are actively seeking genetic solutions that will create crops capable of withstanding erratic environments. In parallel,the agro-chemical industry is producing environmentally sustainable compounds and biostimulants to help combat these problems.

>> How else has climate change changed the way our gardens grow, and what can be done to alleviate its effects? Geoff Dixon explored this issue further.

Professor Geoff Dixon is author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

What is so special about rainbow chard pigments, and what does this tasty plant have in common with cacti? The SCI Horticulture Group explains all, ahead of their appearance at BBC Gardeners’ World Live in Birmingham from 16-19 June.

The origins of chard

Chard (Beta vulgaris, subspecies vulgaris) is a member of the beetroot family and is grown for its edible leaf blades and leaf stems. Chard, sugar beet, spinach and beetroot have all been domesticated from the same wild ancestor species – sea beet (Beta vulgaris, subspecies maritima). Another food crop from the same botanical family is quinoa.

The term chard comes from the 14th century French word carde, which means artichoke thistle.

Nutritional properties

Chard's leaves are a valuable source of mineral nutrients, with a normal serving of 100g containing: 24% of our daily magnesium needs, 17% of iron, 16% of manganese, and 12% of both potassium and sodium. The same portion can provide 22% of our daily vitamin C needs, 13% of vitamin E, and 100% of our vitamin K.

>> What gives chillis their heat? The SCI Horticulture group has explored the weird and wonderful world of chillis.

The edible petioles (leaf stems) of Swiss chard are typically white, yellow, or red. Lucullus and fordhook giant are cultivars with white petioles. Canary yellow has yellow petioles and red-ribbed forms include ruby chard and rhubarb chard. Rainbow chard is a mix of coloured varieties, often mistaken for a variety unto itself.

The pigments that produce these colours belong to a special group – known as the betalains. These pigments are found only in species of one small section of the plant kingdom called caryophyllales. The pigments in the rest of the plant kingdom have different chemical structures, made up of only carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, whereas the betalain chemical structures also contain nitrogen.

Rainbow chard contains betalains, as do cacti, pokeweed, and (above) bougainvillea.

The many uses of chard pigments

The colourful pigments in plants not only contribute to the beauty of our gardens – they advertise the presence of flowers to pollinators or fruits to dispersal agents. Others deter herbivores by tasting bitter or act as a sunscreen to protect from strong ultraviolet light.

The vivid pigments found in chard are particularly useful. Betanin is the best-known pigment from this group and gives rise to the striking colour of beetroot. It is used commercially as a natural food dye, can help preserve food, and contains antioxidant properties.

Betanin, the pigment that makes beetroot (and poop) red.

Some people are unable to metabolise betanin, which gives rise to a phenomenon known as beeturia – where human waste is coloured red by the betanin.

Cooking with chard

When cooking with chard, it can be treated as two separate vegetables – the leafy part and the crunchy petiole. Blitva is a traditional Croatian dish made from the leafy part, often cooked along with potatoes and served with fish.

Blitva is made with chard, potato, olive oil, and garlic.

Chard stalks sautéed with lemon and garlic forms another popular side-dish, while lovers of Italian cuisine can turn rainbow chard into a pesto with pine nuts, parmesan and basil.

Find us at BBC Gardeners’ World Live

From 16-19 June, the SCI Horticulture Group will tell the public all about the hidden chemistry behind their favourite fruit and vegetable plants at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham for BBC Gardeners’ World Live. If you’re curious to learn all about rainbow chard, chillis, and strawberries, pop by and say hello!.

>> Written by the SCI Horticulture Group and edited by Eoin Redahan. Special thanks to Neal Price from Chillibobs, Martin Peacock of ZimmerPeacock, Hydroveg, and The University of Reading Soft Fruit Technology Group for supporting the work of the SCI Horticulture Committee at BBC Gardeners’ World Live.

>> The SCI Horticulture Group brings together those working on the wonderful world of plants.

Which molecules give strawberries their distinctive smell, how are experts using different types of light to grow them all year round, and just how many of them do we eat? The SCI Horticulture Group told us all about this beloved fruit ahead of their appearance at BBC Gardeners’ World Live in Birmingham from 16-19 June.

Where did strawberries originate?

The woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) was first cultivated in the 17th century, but the strawberry you know and love today (Fragaria x ananassa) is actually a hybrid species. It was first bred in Brittany, France, in the 1750s by cross-breeding the North American Fragaria virginiana with the Chilean Fragaria chiloensis.

The strawberry is a member of the rose family, as are many other popular edible fruits such as apples, pears, peaches, and plums. It is the most commonly consumed berry crop worldwide.

People in the UK consume an average 3kg of strawberries every year. Perhaps a certain sporting event has something to do with it…

How many do we eat?

A staggering 9 million tonnes of strawberries are produced globally each year, and their popularity certainly extends to UK shores, and not just during Wimbledon. In the UK alone, the average per capita consumption of strawberries is about 3kg a year!

Domestic strawberry production provides almost all the required fruit for the UK market from March to November; and in 2020, 123,000 tonnes of strawberries were produced within the UK.

This stands in stark contrast to the 50,000 tonnes produced in 1985, when UK strawberries were only produced during June and July. Researchers are currently trying to extend the UK growing season to all year round.

She certainly likes the smell of strawberries, but what gives them that distinctive aroma?

What about the chemistry of their distinctive smell?

The characteristic strawberry aroma consists of many different volatile organic chemicals – more than 360 have been observed in fresh strawberries. Which molecules are present, and in what concentrations, depends on the particular cultivar and how mature or ripe it is.

The most common kinds of chemical are furanones and esters. Esters (such as methyl butanoate) account for more than one third of the observed molecules and 25–90% of the volatiles from any one cultivar.

These molecules are responsible for the fruity and floral notes of the aroma. The most characteristic furanone that gives rise to the characteristic strawberry odour is DMHF.

Pictures like this only increase demand for strawberries out of season.

How to produce strawberries all year...

To optimise strawberry growing conditions, researchers are investigating the influence of temperature, photo-period (response to daily, seasonal, or yearly changes in light and darkness), growth hormones, night-break lighting and CO2 enrichment on flowering and fruiting timing, yield, and quality.

Optimal chilling models are also being developed for both June-bearers and ever-bearers. Critically, a careful and detailed evaluation of the environmental and economic costs of producing winter UK strawberries compared to imports is being undertaken.

Extending the growing season in the UK would have a number of benefits, such as; meeting the increasing demand for out-of-season strawberries while increasing food security, reducing food miles, contributing to public health, providing continued employment, and supporting sustainable farming.

>> Are you a keen gardener? Our resident gardening expert, Geoff Dixon, provides plenty of gardening tips for you on the SCIBlog.

Improving the fruit's nutrient profile

The nutrient content of strawberries is dependent in part on the plant’s growing conditions. The interaction between light intensity and root-zone water deficit stress is being examined to improve berry nutrient content. Researchers are also investigating how to apply this to commercial strawberry production in total environment-controlled agriculture systems.

See how a college in Finland is harnessing LEDs to power a vertical strawberry farm!

LED light colour and strawberry growth

Light emitting diode (LED) lighting increases yields in out-of-season strawberry production. LEDs have a higher energy efficiency than traditional horticultural lighting and come in a range of single colours with varying efficiencies and effects on plant growth.

Red LEDs convert energy into light (and drive photosynthesis) most efficiently, followed by blue, green, and far-red, respectively. However, red light alone is not sufficient for optimum plant growth. Blue light controls flowering, promotes stomatal opening (pores found in various parts of the plant), inhibits stem elongation, and increases secondary metabolites (organic compounds produced by the plant), thereby improving flavour.

Additional green LEDs, which appear white, improve visibility for workers. These lights can also penetrate deeper into the plant canopy, improving photosynthesis. Far-red light produces shade avoidance responses such as canopy expansion and earlier flowering, which can be beneficial for increased light capture and earlier fruiting.

>

>Confirmed strawberry.

Who is carrying out strawberry research in the UK?

The Soft Fruit Technology Group at the University of Reading is just one of the institutions providing research to support the UK strawberry industry. The main areas of research are plant propagation, crop management, and production systems.

Find us at BBC Gardeners’ World Live

From 16-19 June, the SCI Horticulture Group will tell the public all about the hidden chemistry behind their favourite fruit and vegetable plants at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham for BBC Gardeners’ World Live. If you’re curious to learn all about strawberries, chillis, and chard, pop by and say hello!

>> Written by The SCI Horticulture Group. Special thanks to Neal Price from Chillibobs, Martin Peacock of ZimmerPeacock, Hydroveg, and The University of Reading Soft Fruit Technology Group for supporting the work of the SCI Horticulture Committee at BBC Gardeners’ World Live.

What makes chilli peppers so spicy and how do they help with pain relief? The SCI Horticulture Group explained all ahead of their appearance at BBC Gardeners’ World Live in Birmingham from 16-19 June.

This June, the SCI Horticulture Group will tell the public all about the hidden chemistry behind their favourite fruit and vegetable plants. One of the main plants they will feature at the National Exhibition Centre is the humble chilli pepper – and these famous fruit-berries conceal more secrets than you might think…

Where does the chilli originate?

The chilli pepper (Capsicum spp.) is a member of the Solanaceae, the plant family that includes edibles such as potatoes, tomatoes, aubergines, but also poisonous plants such as tobacco, mandrake, and deadly nightshade.

Who brought the chilli pepper to these shores?

The chilli was brought to Europe in the 15th century by Christopher Columbus and his crew. They became acquainted with it on their travels in South and Central America and, shortly thereafter, to India via the Portuguese spice trade.

How varied is the genus?

Of the 42 species in the capsicum genus, five have been domesticated for culinary use. Capsicum annuum includes many common varieties such as bell (sweet) peppers, cayenne and jalapenos. Capsicum frutescens includes tabasco. Capsicum chinense includes the hottest peppers such as Scotch bonnet. Capsicum pubescens includes the South American rocoto peppers, and capsicum baccatum includes the South American aji peppers.

From the five domesticated species, humans have bred more than 3,000 different cultivars with much variation in colour and taste. The chilli and bell peppers that we eat are the fruit – technically berries – that result from self-pollination of the flowers.

>> The SCI Horticulture Group brings together those working on the wonderful world of plants.

And we eat a lot of them?

Today, chilli peppers are a global commodity. In 2019, 38 million tonnes of green chilli peppers were produced worldwide, with China producing half of the total. Spain is the largest commercial grower of chillies in Europe.

Capsaicin helps give chilli peppers their heat

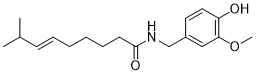

What makes chillies hot?

Capsaicin is the main substance in chilli peppers that provides the spicy heat. It binds to receptors that detect and regulate heat (as well as being involved in the transmission and modulation of pain), hence the burning sensation that it causes in the mouth.

In humans, these receptors are present in the gut as well as the mouth (in fact, throughout the peripheral and central nervous systems) – hence the after-effects of eating too much chilli. Capsaicin, however, is not equally distributed in all parts of pepper fruit. Its concentration is higher in the area surrounding the seeds.

>> Get tickets for Gardeners’ World Live 2022 and pop by our stand to say hello!

How do you measure chilli heat?

The Scoville Heat Unit Scale is used to classify the strength of chilli peppers. Scoville heat units (SHU) were named after American pharmacist Wilbur Scoville who devised a method for rating chilli heat in 1912.

The ludicrously hot Dragon’s Breath chilli

This method relied on a panel of tasters who diluted chilli extract with increasing amounts of sugar syrup until the heat became undetectable. The greater the dilution to render the sample’s heat undetectable, the higher the SHU rating. Pure capsaicin measures 16,000,000 SHU.

The capsaicin content of chilli peppers varies wildly, as is reflected in the SHUs of the peppers below:

- Bell (Sweet peppers) = 0 SHU

- Jalapeno = 5,000 SHU

- Scotch Bonnet = 100,000 SHU

- Naga Jolokia = 1,040,000 SHU

- Carolina Reaper = 1,641,183 SHU

- Dragon’s Breath = 2,480,000 SHU

Dispersal vs. protection – why do chillies contain capsaicin?

The seeds of chillies are dispersed in the wild by birds who do not have the same receptors as mammals and, therefore, are unaffected by capsaicin. Perhaps chillies have evolved to prevent mammals from dispersing their seeds?

Capsaicin has also been shown to protect the plant against fungal attack, thus helping the fruit to reach maturity and the seeds to be dispersed before succumbing to rot. This antifungal property can also be put to good use in helping to preserve foods for human consumption.

How did chilli help win a Nobel Prize?

Capsaicin was pivotal in the research that led to the award of the 2021 Nobel Prize in physiology and medicine to David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian for their discoveries of receptors for temperature and touch.

The two US-based scientists received the accolade for describing the mechanics of how humans perceive hot, cold, touch, and pressure through nerve impulses. The research explained at a molecular level how these stimuli are converted into nerve signals, but the starting point for the study was work with capsaicin from the humble chilli pepper.

Capsaicin in medicine

Capsaicin is used as an analgesic (a pain reliever) in topical ointments, nasal sprays, and patches to relieve chronic and neuropathic pain. Clinical trials continue to investigate the potential of capsaicin for a wide range of additional pain indications and as both an anti-cancer and anti-infective agent.

>> Special thanks to Neal Price from Chillibobs, Martin Peacock of ZimmerPeacock, Hydroveg, and The University of Reading Soft Fruit Technology Group for supporting the work of the SCI Horticulture Committee at BBC Gardeners’ World Live.

>> Our resident gardening expert, Geoff Dixon, provides plenty of gardening tips on the SCIBlog.

How do green spaces, gardens as well as fruit and vegetables impact our health and wellbeing? Professor Geoff Dixon tells us more.

‘We are what we eat’ is an aphorism that is becoming much better understood both by the general public and by healthcare professionals. Similarly, ‘we are where we live’ is gaining greater appreciation. Both these pithy observations underline the social and economic importance of horticulture and the allied art of gardening.

An exuberant display of flowers – what can be better for the soul?

Few things stimulate the human spirit more than a fine, colourful display of well grown and presented flowers. Seeing and working with green and colourful plants is increasingly recognised for its psychological power, reducing stress and increasing wellbeing. In our increasingly urbanised society, with myriads of high-rise housing blocks, the provision of well-tended parks and gardens is not a luxury – it is essential.

Hospital patients recover more quickly when they can see and sit in green spaces. Equally, providing access to gardens and gardening for schools should be a vital part of the children’s environment. They gain an understanding of biological mechanisms and the equally important need for conserving biodiversity and controlling the rate of climate change.

The recently published National Food Strategy emphasised the importance of fruit and vegetables as a major part of our diets. Both fruit and vegetables provide essential vitamins, nutrients and fibres which consumed over time diminish the incidence of cancers, coronary, strokes and digestive diseases.

Apricots are high in catechins.

Eating varying types of fruit and vegetables increases their value – apricots, for example, are high in catechins which are potent anti-inflammatory agents. Members of the brassica (cabbage) family are exceptionally valuable for mitigating diseases of ‘modern society’. All contain glucosynolates, which evolved as means for combating pest and pathogen attacks and co-incidentally provide similar services for humans. Watercress – an aquatic brassica – is rich in vitamins A, C and E, plus folate, calcium and iron. Its high water content means portions consumed fresh or as soups are low in calories.

Watercress – an aquatic brassica boasts numerous health benefits.

These messages and facts are now being recognised both publicly and politically, and not before time. For the past 50 years the universal panaceas have been pharmaceutical drugs. In moderation, these have been of immense value. Use to excess is both counterproductive and needlessly expensive health-wise and financially.

Returning to Grandma’s advice, ‘an apple a day keeps the doctor away’, supports both individual and planetary good health.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

There was a happening in York recently – a Hemp Happening – organised by SCI’s Agrisciences Group and Biovale. It took place at York’s STEM Centre and explored the issues around growing and using industrial hemp. Despite these issues, there is a growing demand for hemp fibre and shiv as we look to use sustainable natural fibres and move to a low-carbon economy.

In 10 years’ time, you’ll walk out of your hemp-insulated home, wearing your hemp fibre t-shirt, polishing off the last of your hemp and beet burger, before heading to work in your hemp seed oil-powered car.

Is this scenario fantastical? Yes, obviously, but as delegates attending Hemp Happening explained on 6 April, all of these products exist right now. The sheer breadth of them underlines what a useful and versatile material hemp is. If enabled through policy, hemp could play a big part in our low-carbon future. Here are five ways it could make a significant difference.

1. Carbon sequestration

Hemp has much-vaunted carbon-sequestering potential which, given our climate change travails, could prove extremely useful. Some experts say it is even better at capturing atmospheric carbon than trees. According to SAC Consulting, industrial hemp absorbs nine to 13 tonnes of CO2 per hectare. To put hemp’s absorption capacity into context, hemp market specialists Unyte Hemp said it absorbs 25 times more CO2 than a forest of the same size.

Of course, that’s all very well, but how do you make sure this carbon remains sequestered?

2. A future heavyweight champion?

One fitting home for hemp (and the carbon it has captured) is in construction, especially given the carbon-intensive nature of the industry. So, with the pressure intensifying to replace and retrofit the UK’s inefficient building stock, hemp is well placed to reduce emissions and improve building performance.

Hemp is not just used in insulation materials due to its excellent thermal performance characteristics. It is also used in rendering buildings and for non-load bearing blocks in construction. Indeed, hempcrete blocks, which are made from hemp shiv, lime, and sand or pozzolans, have a net carbon negative footprint.

Hemp is used in everything from food supplements to medicines, cosmetics, and construction products.

3. Farmer’s friend

Hemp also helps the earth. As flash flooding strips our soils, the plant’s root density and deep structure protects against soil erosion and mitigates compaction. Hemp also provides nutrients to help maintain soil health, making it useful in crop rotation.

As insect populations dwindle, the role of pesticides and herbicides are coming into sharper relief. In that respect, hemp has a natural advantage over other crops as it doesn’t require pesticides and fertilisers.

4.The Swiss Army knife of materials

We have long heard of the health benefits of hemp-derived products such as cannabidiol oil (or CBD oil), but pretty much the whole plant can be used. Its seeds are rich in omega-3, omega-6, and fatty acids, and help fend heart problems.

As mentioned above, the fibrous part of the plant sequesters carbon and produces low-carbon materials for construction, while its roots are used to treat joint pain and for deep tissue healing.

And then we have hemp for bioethanol production and even hemp seed veggie burgers. The list goes on; so, there are many ways for farmers to make money from it.

>> What can be done to make our soils healthier? Take a look at our blog on solving soil degradation.

Hemp has excellent insulation properties.

5. Non-thirsty textiles

I bet you know at least one person with a bamboo t-shirt or socks. Hemp has similar textile potential to its super material cousin. As the fashion industry interrogates its wayward past, the pressure will increase to lighten the footprint of clothing materials. Estimates vary, but hemp is said to need less than half the water required to cultivate and process than cotton textiles and its toughness is handy in long-lasting carpeting.

Mr Elephant, could you step through please?

Hemp has been heralded as a wonder material for decades but there is that elephant in the room. The restricted uses of hemp-related materials curb the extent to which it can be grown in the UK. At the event, delegates noted that outdated legislation, lack of government support, and education are among the factors holding back the growth of hemp on an industrial scale.

And yet, there is growing demand for natural materials that tackle climate change, especially those that sequester carbon. With pension funds increasingly divesting from fossil fuels, and the ever growing importance of corporate sustainability in business, sustainable materials such as hemp are now more attractive.

Arguably the most exciting contribution of the day was the mention of zero-cannabinoid industrial hemp. Even though the THC content levels present in hemp are low (compared to the high levels found in marijuana) and it’s unattractive as a THC source, hemp is still very strictly regulated in the UK compared to North America and the rest of the EU.

One participant mentioned that hemp genes could be edited to remove the cannabinoid – and, if that were to be achieved, it could change everything. Then we would really see hemp happening in the UK.

>> Interested in more events like this one? Visit our Events pages.

Crop rotation, seaweed extracts, lime, and a range of organic materials can all improve soil health and crop yields. Professor Geoff Dixon shows you several ways to improve your soil.

Rapidly rising costs of living are affecting all aspects of life. Increasing costs of fertilisers are affecting food production, both commercially and in gardens and allotments.

Wholesale prices of fertilisers have jumped four-fold from £250 to £1,000 per tonne within six months. All forms of garden fertilisers are now much more expensive. Crops, especially vegetables, only thrive if provided with adequate nutrition (see nitrogen-deficient lettuce below). Consequently, fertiliser use must become more efficient.

Nitrogen deficiency in lettuce.

Healthy, fertile soils achieved through good management are key to this process. That ensures roots can take up the nutrients needed in quantities that result in balanced, healthy growth.

Soil pH is a major regulator of nutrient availability for roots. Between pH 6.5 to 7.5, the macro nutrients, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are fully available for root uptake. Below and above these values, nutrient absorption becomes less efficient.

>> How much soil cultivation do you need for your vegetables? Find out more in Prof Dixon's blog on cultivation.

As a result, soluble nutrients are wasted and washed by rainfall below the root zones. Acidic soils can be improved by liming in the autumn. Sources of lime derived from crushed limestone require up to six months to cause changes in soil pH values. Lime should be used in ornamental gardens with caution as it can result in micronutrient deficiencies.

Iron deficiency in wisteria.

Soil health and fertility are greatly increased by adding organic materials such as farmyard manure and well-made composts. Increasing soil carbon content helps mitigate climate change while raising fertiliser use efficiencies.

Beneficial soil biological life such as earthworms, insects, benign bacteria and fungi are greatly encouraged when you increase soil humus content. Using crop rotations, which include legumes, raises natural levels of soil nitrogen. This is a result of legumes’ symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria.

Leafy vegetables such as brassicas require large amounts of nitrogen and, hence, should follow legumes in a rotation. Avoiding soil compaction encourages adequate aeration, benefiting root respiration and providing oxygen for other organisms.

Organic materials are of great value in ornamental gardens when applied as top dressings in late autumn or early spring. This provides two benefits: a slow release of nutrients into the root zones as decomposition occurs, and prevention of weed growth.

Inorganic fertiliser use can be further minimised by using proprietary seaweed extracts. These contain macro- and micro-nutrients plus several natural biostimulant compounds that aid healthy ornamental plant growth and flowering (illustration no 3 rose Frűhlingsgold).

Rose frűhlingsgold

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science.

How do flowers use fragrance to attract pollinators, and how do pollution and climate change hamper pollination? Professor Geoff Dixon tells us more.

‘Fragrance is the music of flowers’, said Eleanour Sophy Sinclair Rohde, an eminent mid 20th century horticulturist. But they are much more than that. Scents have fundamental biological purposes. Evolution has refined them as means for attracting pollinators and perpetuating the particular plant species emitting these scents.

There are complex biological networks connecting the scent producers and attracted pollinators within the prevailing environment. Plants flowering early in the year are generalist attractors. By late spring and early summer, scents attract more specialist pollinators as shown by studies of alpines growing in the USA Rocky Mountains. This is because there is a bigger diversity of pollinator activity as seasons advance. Scents are mixtures of volatile organic compounds with a prevalence of monoterpenes.

Environmental factors will affect scent emission. Natural drought, for example, changes flower development and reduces the volumes and intensity of scent production. The effectiveness of pollinating insects, such as bees, moths, hoverflies and butterflies is reduced by aerial pollution.

Pheasant’s eye daffodils (Narcissus recurvus).

Studies showed there were 70% fewer pollinators in fields affected by diesel fumes, resulting in lower seed production. Pollinating insects do not find the flowers because nitrogenous oxides and ozone change the composition of scent molecules.

Extensive studies of changes in flowering dates show that climate change can severely damage scent–pollinator ecologies. Over the past 30 years, blooming of spring flowers has advanced by at least four weeks. Earlier flowering disrupts the evolved natural synchrony between scent emitters and insect activity and their breeding cycles. In turn that breaks the reproductive cycles of early flowering wild herbs, shrubs and trees, eventually leading to their extinction.

The lilac bush, known for its evocative scent.

Heaven scent

Scents provide powerful mental and physical benefits for humankind. Pleasures are particularly valuable for those with disabilities especially those with impaired vision. Even modest gardens can provide scented pleasures.

Bulbs such as Pheasant’s eye daffodils (Narcissus recurvus) (illustration no 1), which flower in mid to late-spring, and lilacs (illustration no 2) are very rewarding scent sources.

Sweetly perfumed annuals such as mignonette, night-scented stocks, candytuft and sweet peas (illustration no 3) are easily grown from garden centre modules, providing pleasures until the first frosts.

Sweet peas are easily grown from garden centre modules.

Roses are, of course, the doyenne of garden scents. Currently, Harlow Carr’s scented garden, near Harrogate, highlights the cultivars Gertrude Jekyll, Lady Emma Hamilton and Saint Cecilia as particularly effective sources of perfume. For larger gardens, lime or linden trees (Tilia spp) form profuse greenish-white blossoms in mid-season, laden with scents that bees adore.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

The plant-based meat alternative market is growing rapidly, and cell-cultured meats could be coming soon to your dinner plate once they receive regulatory approval. Gavin Dundas, Patent Attorney at Reddie & Grose, provides his expert perspective on the state of the meat alternative market.

Which is receiving more emphasis based on patent activity: lab-grown meat or plant-based meat alternatives?

Comparing cultivated meat to plant-based meat is a bit like comparing apples and oranges.

Plant-based meat is here - it’s in shops, and it’s in growing numbers of restaurants and fast-food outlets. Even McDonald’s – arguably the world’s most well-known hamburger outlet – released its first plant-based burger in the UK on 13 October 2021: the aptly-named McPlant. The McPlant has been accredited as vegan by the Vegetarian Society, and includes vegan sauce, vegan cheese and a plant-based burger co-developed with Beyond Meat.

Cell-cultured meat is a very different prospect, as cellular agriculture is more high-tech, so companies entering that sector require a higher degree of specialised technical expertise. Companies delving into cultivated meat also require a fair bit of funding, as cultivated meat has not been approved for sale in any country other than Singapore, so it is not yet possible to sell their products to consumers.

The reality at the moment is that plant-based meat alternatives have a huge head-start in the marketplace, while cultivated meat is not yet on sale in most countries. So, for most new companies looking to make money in the alternative protein market, plant-based products are likely to be the easier way to start.

On the other hand, this means that the plant-based meat market is more crowded already, while cultivated meat companies are investing in the hope of getting a bigger share of that market once it matures.

In which food types have you seen a particular surge in patent applications, for example plant-based meat alternatives or lab-grown meat?

Based on searches using patent classification codes commonly used for plant-based meats and lab-grown meat (known as ‘cell-cultured meat’ or ‘cultivated meat’), it appears that there are significantly more patent applications in the field of plant-based meats, but that patent filings relating to cultivated meat are growing more quickly.

Of all the patent publications relating to plant-based meats, 15.2% were published since the start of 2020. Of the patent publications relating to cultivated meats, 27.6% were published since the start of 2020.

This outcome is probably not surprising. Plant-based meats have been around much longer and are now widely established in the market, so many more companies have had time and opportunity to file patent applications for innovations in this area. Cultivated meats are at an earlier stage in their development, but with a large number of new companies having been formed in this area in the last few years, it is not surprising that this has resulted in a high growth rate of patent applications as cultivated meat gets closer to commercial reality.

Beyond Meat’s plant-based meat substitutes have reached the mainstream. | Jonathan Weiss/Shutterstock

How much movement has there been on the equipment and other innovations that will facilitate large-scale meal alternative manufacturing?

There is a huge difference between small-scale production of cultivated meat in a laboratory, and the large-scale manufacturing that would be needed to supply supermarkets and restaurants throughout whole countries and - eventually - the whole world.

Growing meat using cellular agriculture involves the use of animal cell lines to grow animal products in bioreactors, where the cells are immersed in a growth medium that feeds nutrients to the cells as they develop. Over the last decade there have been huge advances in these processes, but as demand for cultivated meat grows there will definitely be continued innovation to improve efficiency and scale-up manufacturing capacity.

Commercial growth medium is currently costly, so the development of more cost-effective growth media is likely to be an area of much research. Another ongoing challenge is the development of high-quality cell lines and scaffold materials that are suitable for high-quality, large-scale production.

Bioreactor design is also expected to be a big area of innovation - up until now, bench-top bioreactors have in most cases been sufficient to meet the demands of cultivated meat R&D, but as demand increases bigger and better bioreactors will be needed. A particular challenge will be to design bioreactors capable of growing thick tissue layers on a commercially viable scale.

While there is scope for innovation in all of these areas, some companies are already ready to manufacture their cultivated meat products on a large scale. Future Meat Technologies, for example, opened its first industrial cultivated meat production facility in June 2021 in Rehovot, Israel - that facility is reportedly capable of producing 500kg of cultivated meat products every day. In November 2021, Upside Foods opened its first large-scale cultivated meat production plant in Emeryville, California, with the capacity to produce 22,680kg of cultured meat annually.

At the moment, however, a lack of regulatory approval is holding back cultivated meat production. While there are a number of companies that apparently have products ready for market, many will be unwilling to plough huge amounts of money into large-scale manufacturing facilities until they have regulatory approval that lets them actually sell their products.

Thinking of filing a chemistry patent in 2022? Here’s what you need to know.

The UK has cutting-edge companies in the cultivated meat field.

Have any innovations or areas of innovation struck you as particularly exciting? If so, could you tell us more about them?

I am a meat-eater trying to cut down on my consumption of meat, due to a mixture of environmental and ethical motivations. So, as a consumer I’ve been very excited to see the arrival of plant-based meat into the mainstream.

I am particularly excited to try cultivated meat once it is approved for sale. Not long ago ‘lab-grown’ meat seemed like science-fiction, so to get to a point where you can go out and buy it will be incredible. So many people are unwilling to cut down on meat because they like the taste, and because their favourite meals are meat-based, so cultivated meat might hopefully give that same experience with fewer of the drawbacks of animal meat.

I am also excited to see the diversity of cultivated meat products. Cultivated meat chicken nuggets and beef burgers are the products that spring to mind when cell-cultured meat is mentioned, but there are companies out there developing cultivated bacon, pork belly, salmon and tuna, to name a few.

What are the chemistry challenges for those creating plant-based meat alternatives? Find out here.

Given what you know about the patent landscape, where do you think the meat alternative industry is heading, and at what sort of pace do you foresee significant change?

I think the meat alternative industry is only going to continue to grow, as concern over the environmental impact of our eating habits is growing, and the quality and availability of meat alternatives is getting better.

The plant-based meat industry is already doing well, and I expect it to continue on its upward trajectory. I expect companies in this field to continue to file patent applications for their innovations, and eventually we might see some of those patents being enforced to safeguard valuable market shares for the patent owners.

Cultivated meat is the sector that seems to be poised for the most significant change. At the moment, the lack of regulatory approval seems to be the thing holding it back, but if that hurdle is removed there are UK companies aiming to get cultivated meats into shops by 2023. The UK is lucky enough to be home to a number of cutting-edge companies in the field, and a recent report by Oxford Economics researchers forecast that cultivated meat could be worth £2.1 billion to the UK economy by 2030.

The idea of cultivated meat is unlikely to appeal to everyone, so I imagine that it will start out as something of a novelty, but I’d expect to see the availability and range of cultivated meat products grow significantly over the next decade.

Edited by Eoin Redahan. You can read more of his work here.

How much soil cultivation do you need for your vegetables? Professor Geoff Dixon explains all.

Cultivating soil is as old as horticulture itself. Basically, three processes have evolved over time. Primary cultivation involves inversion which buries weeds, adds organic matter and breaks up the soil profile, encouraging aeration and avoiding waterlogging.

Secondary cultivation prepares a fine tilth as a bed for sowing small seeded crops such as carrots or beetroot. In the growing season, tertiary cultivation maintains weed control, preventing competition for resources (illustration no. 1) such as light, nutrients and water while discouraging pest and disease damage.

Lettuce and seed competition

The onset of rapid climate change encouraged by industrialisation has focused attention on preventing the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Ploughing disturbs the soil profile and accelerates the loss of carbon dioxide from soil.

It is also an energy intensive process. Consequently, many broad acre agricultural crops such as cereals, oilseed rape and sugar beet are now drilled directly without previous primary cultivation. An added advantage is that stubble from previous crops remains in situ over winter, offering food sources for birds. The disadvantages of direct drilling are: increased likelihood of soil waterlogging and reduced opportunities for building organic fertility by adding farmyard manure or well-made composts.

Overall, primary and secondary cultivation benefit vegetable growing. The areas of land involved are far smaller and the crops are grown very intensively. Vegetables require high fertility, weed-free soil, good drainage and minimal accumulation of soil-borne pests and diseases.

Frost action breaking down soil clods

Digging increases each of these benefits and provides healthy physical exercise and mental stimulation. Frost action on well-dug soil breaks down the clods (illustration no. 2). Ultimately, fine seed beds are produced by secondary cultivation (illustration no. 3), which encourage rapid germination and even growth of root and salad crops.

Tertiary cultivation to prevent weed competition is also of paramount importance for vegetable crops. Competition in their early growth stages weakens the quality of root and leafy vegetables, destroying much of their dietary value. Regular hoeing and hand removal of weeds are necessities in the vegetable garden.

Raking down soil producing a fine tilth

Ornamental and fruit gardens similarly benefit from tertiary cultivation. Weeds not only provide competition but are also unsightly, destroying the visual image and psychological satisfaction of these areas.

Lightly forking over these areas in spring and autumn encourages water percolation and root aeration. Once established, ornamental herbaceous perennials and soft and top fruit areas benefit greatly from the addition of organic top dressings. Over several seasons these will augment fertility and nutrient availability.

Written by Professor Geoff Dixon, author of Garden practices and their science, published by Routledge 2019.

A sprig of thyme to fight that cold… Turmeric tea after exercising… An infusion of chamomile to ease the mind… As we move with fresh resolution through January, Dr Vivien Rolfe, of Pukka Herbs, explains how a few readily available herbs could boost your health and wellbeing.

The New Year is a time when many of us become more health conscious. Our bodies have been through so much over the last few years with Covid, and some of us may need help to combat the January blues. So, can herbs and spices give us added support and help us get the new year off to a flying start?

The oils in chamomile have nerve calming effects.

Chamomile and lavender

We may wish to ease ourselves into the year and look for herbs to help us relax. The flowers from these herbs contain aromatic essential oils such as linalool from lavender (Lavandula) and chamazulene from German chamomile (Matricaria recutita) that soothe us when we inhale them (López et al 2017). Chamomile also contains flavonoids that are helpful when ingested (McKay & Blumberg 2006).

If you have a spot to grow chamomile in your garden, you can collect and dry the flowers for winter use. Lavender is also a staple in every garden and the flowers can be dried and stored. Fresh or dry, these herbs can be steeped in hot water to make an infusion or tea and enjoyed. As López suggests, the oils exert nerve calming effects. Maybe combine a tea with some breathing exercises to relax yourselves before bed or during stressful moments in the day.

Thyme is a handy herbal remedy. Generally, the term herb refers to the stem, leaf and flower parts, and spice refers to roots and seeds.

>> The plant burgers are coming. Read here about the massive growth of meat alternatives.

Andrographis, green tea and thyme

Many people may experience seasonal colds throughout the winter months and there are different herbal approaches to fighting infection. Andrographis paniculata is used in Indian and traditional Chinese medicine and contains bitter-tasting andrographolides, and in a systematic review of products, the herb was shown to relieve cough and sore throats symptoms in upper respiratory tract infection (Hu et al 2017).

Gargling with herbal teas is another way to relieve a sore throat, and the benefits of green tea (Camellia sinensis) have been explored (Ide et al 2016). I’m an advocate of garden thyme (Thymus vulgaris) which contains the essential oil thymol and is used traditionally to loosen mucus alongside its other cold-fighting properties.

You could experiment by combining thyme with honey to make a winter brew. I usually take a herbal preparation at the sign of the very first sneeze that hopefully then stops the infection progressing.

Shatavari (pictured) is said to improve strength, and ashwagandha can help recovery.

Shatavari and ashwagandha

We may start the new year with more of a spring in our step and wishing to get a little fitter. As we get older, we may lose muscle tissue which weakens our bones and reduces our exercise capability. Human studies have found that daily supplementation with shatavari (Asparagus racemosus) can improve strength in older women, and ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) can enhance muscle strength and recovery in younger males (O’Leary et al 2021; Wankhede et al 2015).

These herbs are known as adaptogens and traditionally they are used in tonics or to support fertility. The research to fully understand their adaptogenic activity or effects on muscle function is at an early stage. Other herbs such as turmeric may help muscle recovery after exercise. I brew a turmeric tea and put it in my water bottle when I go to the gym.

>> How is climate change affecting your garden? Find out here.

Lemon balm is easy to grow but might want to take over your garden.

Easy on the body. Easing the mind

Depending on your resolutions, you could use herbs and spices to add lovely flavours to food to try and reduce your sugar and salt intake. Liquorice is a natural sweetener, and black pepper and other herbs and spices can replace salt.

You could also bring joy to January by growing herbs from seed on a windowsill or in a garden or community space. Mint, lemon balm, lavender, thyme, and sage are all easy to grow, although mint and balm may take over!

All make lovely teas or can be dried and stored for use, and research is also showing that connecting with nature – even plants in our homes – is good for us.

You can read more about medicinal and culinary properties of herbs at https://www.jekkas.com/.

If you wish to learn more about the practice of herbal medicine and the supporting science, go to https://www.herbalreality.com/.

>> Dr Viv Rolfe is head of herbal research at Pukka Herbs Ltd. You can find out more about Pukka’s research at https://www.pukkaherbs.com/us/en/wellbeing-articles/introducing-pukkas-herbal-research.html, and you can follow her and Pukka on Twitter @vivienrolfe, @PukkaHerbs.

Edited by Eoin Redahan. You can find more of his work here.

Greenhouse gas emissions statistics can be misleading. At a recent SCI webinar on the Future of Agriculture, the Agrisciences Committee put its finger on some glaring gaps in the figures.

If all of the cows in the world came together to form a country, that nation state would be the second highest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions in the world.

McKinsey Sustainability’s statistic was certainly startling. However, Agrisciences Group Chair Jeraime Griffith mentioned other equally striking figures in his wrapup of the social media discussion generated at COP26.

In his talk as part of the Agrisciences Committee’s COP26 – What does it mean for the future of agriculture? webinar on 7 December, Griffith also noted that:

- farming accounts for more than 70% of the freshwater used worldwide, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

- and 31% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions come from agrifood systems, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation.

On the face of it, these figures are sobering; yet, like many agriculture-related figures, they don’t tell the full story.

Insane in the methane

Kathryn Knight felt that agriculture received negative press at COP26 in relation to greenhouse gas emissions. ‘It doesn't seem to take into account carbon sequestration (capturing and storing atmospheric carbon dioxide),’ said the Research & Technology Manager of Crop Care at Croda. ‘Why isn’t that being brought into the equation when we’re talking about carbon and agriculture?’

Martin Collison expanded on this point. He emphasised the need to separate carbon emissions by system – such as extensively grazed livestock animals and those fed on grain – and to account for systems that sequester carbon in the soil. The co-founder of agricultural consultancy Collison & Associates also pointed out the problem with bundling all our greenhouse gases as one.

Greenhouse gas emissions are sometimes unhelpfully bundled together, instead of being separated by gas and agricultural system.

‘We count methane in the same way we emit carbon,’ he said. ‘When we emit carbon, it’s in the atmosphere for 1,000 years, but with methane it’s 12 years. The methane cycle is a lot, lot shorter.’

And the difficulties with the statistics don’t end there. For example, countries often announce impressive emission reductions without taking trade into account. This, of course, gives the figures a greener gloss.

‘To me, there's a need to be more up front with a lot of the data because agriculture and food are traded around the world,’ he added. ‘A lot of the emissions data ignore what we trade.

‘In the UK, we make big claims about how fast we’ve progressed with carbon emissions, but if you look at what we consume, the progress is much much slower. The things we produce less of, we import.’

>> SCI was at COP26 too! Read about the role of chemistry in creating a greener future.

Full of hot air?

Emissions trading also serves to blur the picture. For Jeraime Griffith it is an unsatisfactory solution. ‘In terms of carbon trading, we have cases where the higher emitters continue producing in the way they’ve always been producing,’ he said.

‘It doesn't bring in any restrictions on the amount of carbon they emit; it just shifts the problem somewhere else. I don't know how carbon trading benefits us getting to Net Zero. It just seems to be kicking the ball farther down the road.’

Is emissions trading part of the solution or part of the problem?

So, when you take into account 1. emissions trading, 2. the absence of food imports in data sets, 3. the bundling together of different greenhouse gases in emissions figures, and 4. the failure to take carbon sequestration into account, it’s clear that many of the statistics we receive are incomplete.

‘There’s lots of complexity behind the numbers and we tend to lump all of it together,’ Collison said. ‘There’s a need to go much much further.’

>> SCI’s Agrisciences Group is a unique multidisciplinary network covering the production, protection and utilisation of crops for food and non-food products. It has 250 members including academic and industry leaders, researchers, consultants, students, and retired members. If you’re interested in joining the group, go to: www.soci.org/interest-groups/agrisciences

Gardens in December should, provided the weather allows, be hives of activity and interest. Many trees and shrubs, especially Roseaceous types, offer food supplies especially for migrating birds.

Cotoneaster (see image below) provides copious fruit for migrating redwings and waxwings as well as resident blackbirds. This is a widely spread genus, coming from Asia, Europe and northern Africa.