Following her insightful SCItalk on Diversity, Equality and Inclusion, Ijeoma Uchegbu, Chair in Pharmaceutical Nanoscience at UCL's School of Pharmacy speaks with Darcy Phillips.

Tell us about your career path to date.

I trained as a pharmacist and then did a PhD at the School of Pharmacy on drug delivery using nanosystems. After about two years of postdoctoral scientist work, I was appointed to a lectureship at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow. After five and a half years, I was appointed to a professorship in 2002. I then joined the School of Pharmacy as a Professor of Pharmaceutical Nanoscience in 2006 and UCL in 2012.

My work has focused on understanding how drug transport may be controlled in vivo using nanoscience approaches. I co-founded Nanomerics Ltd. with my long-term collaborator – Professor Andreas G. Schätzlein – and next year will see Nanomerics take the technologies developed in academia into clinical testing. This is a huge milestone for our small company and for us personally. I liken this milestone to sending your only child off into the big wide world, and so we are understandably nervous and excited in equal measure!

Science was a refuge for me as I moved countries as a teenager – from London, the city of my birth, to a small town in Nigeria called Owerri. Science subjects were the only subjects that were common on the secondary school curricula of both countries. I really had no other option. I fell in love with science because it was familiar.

Which aspects of your work motivate you the most?

The joy of discovery really gives one a high and this is what I enjoy the most. Validation of one’s discoveries by other members of the scientific community cements the high and when one’s ideas are evidenced first by experimentation and then appreciated by one’s peers, there is no other feeling in the world quite like it.

What has been your proudest achievement?

Getting my professorship so soon after my appointment to a lectureship at the University of Strathclyde is up there with the greatest moments of my career, as is bringing up my daughters at the same time. Oh dear – there are far too many moments to mention, to be honest! Every day I don’t get a rejected paper or grant is really a proud day. Rejections are 90% of a scientist’s life.

You spoke recently at our SCItalk on diversity, equality and inclusion and the importance of data. Could you give us a summary on why this is so important?

To produce good quality science outputs with the maximum impact we need a variety of individuals asking and answering the most profound of research questions. We need more data on diseases and conditions that affect women and more data on the genomics affecting the global southern majority. We need answers to the pressing questions on health outcomes in the poorest in our UK society. Well, you get the picture. We need high quality data on these largely forgotten issues.

What do you think are the next key steps to making STEM more diverse and inclusive?

We first need to recognise that a problem exists. This is the first step. The data on underrepresentation needs to be at the forefront of our thinking when we are making decisions. We need funders to acknowledge the deficit in the current ways of doing things and then commit to act appropriately. The oddest thing about a skewed and unequal system is that we all lose out when there are entrenched inequalities. Even those that think that they are gaining from the current system are not.

We catch up with Zoë Henley, a Medicinal Chemistry Lead at GSK and recent recipient of a Rising Star Award in the category of Science & Engineering

Tell us about your career path to date.

Growing up, I loved science and have early memories of playing with my beloved chemistry set. However, it wasn’t until my A-levels that I knew I wanted to study chemistry at university. I had an inspiring chemistry teacher who supported me to apply, and I ultimately gained a first-class MSci chemistry degree from the University of Bristol.

I joined GSK as an Associate Scientist in 2006 and in my early career I was focused on identifying new molecules to treat respiratory diseases. As a chemist, I use my synthetic and medicinal chemistry skills to identify potential drug candidates, one of which reached Phase 2 clinical trials in patients for the treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, which is a life-threatening lung condition with no current cure. I have also led discovery efforts on early-phase research projects to validate the exact role a potential therapeutic target plays in a disease, which is critical for initiating a drug discovery programme.

Through my work, I developed deep technical skills in inhaled drug design and was appointed chair of a technical network for inhaled drug discovery programmes within GSK.

Alongside my work in the laboratory, I also developed my technology skills to become the lead user in Europe for drug compound design and data analysis software.

I was promoted to a Scientific Investigator in 2013 and achieved my PhD in 2014, through a collaborative programme between GSK and the University of Strathclyde. In September 2021, I was promoted to Team Leader.

Over the period I have been a team leader, I have supported 12 scientists and have had the opportunity to mentor graduate chemists and supervise one-year industrial placement students. I am currently a project Medicinal Chemistry Lead and have three direct reports who I support in their professional and scientific development at GSK.

‘I am passionate about science and the job that I do, and am committed to being an advocate for female leaders in chemistry.’ Image: Zoë Henley

Which aspects of your work motivate you the most?

I find the job of a medicinal chemist fascinating and highly rewarding. As a chemist, I have the opportunity to make the molecule that becomes a medicine to help patients, and this is my greatest motivation. Medicinal chemistry is a fast-paced, constantly evolving field that requires diverse skill sets. I find it refreshing to work within a diverse team, in particular working internationally across our global organisation, where I have had experience of working with colleagues across scientific disciplines and from different cultures and backgrounds who bring varied perspectives.

You were recently recognised with a Rising Star Award in the category of Science & Engineering, do you have any advice for anyone starting out their career in this field?

I am passionate about science and the job that I do, and am committed to being an advocate for female leaders in chemistry. For those starting out in this field, I would encourage them to follow their hearts and make well-informed career and personal choices to fulfil their dreams. Whenever I have had decisions to make, I have relied on close friends and mentors for advice, and I would encourage others to identify role models and seek their mentorship. I would also advise pursuing anything you feel passionate about. This might mean, for example, developing a new skill or gaining deeper expertise.

‘GSK as an organisation is highly supportive of flexible working, and within my own department I have continually had support for my professional development, in particular when I returned to work after one year maternity leave.’ Image: Zoë Henley

You’ve been working at GSK for a number of years now – can you tell us a bit more about how they’ve supported you in your career and allowed you to balance this with family life?

Throughout my career at GSK I have had so many opportunities to develop professionally and personally. Alongside continuously developing my technical skills, I have been able to carry out a PhD whilst still a full-time employee of GSK, participated in STEM outreach activities, had supervisory responsibility for both GSK employees and PhD students on collaborative projects, and I have been asked to take leadership roles in many different settings.

In 2019, I became mum to my son Sam, and I have since progressed my career whilst working part-time. I had very few female role models until I came to GSK, where the number of female chemists is high and there were many who had families and successful careers, which gave me confidence that I could have the same.

GSK as an organisation is highly supportive of flexible working, and within my own department I have continually had support for my professional development, in particular when I returned to work after one year maternity leave. My manager was highly supportive of my continued trajectory towards taking a leadership role and supported me in applying for a Deep Dive Career Programme at GSK, which is a competitive programme for future leaders who want to actively shape their career journey.

The programme allowed me to set out a detailed personal development plan and helped to expand my network. The leaders of my department also offered me managerial responsibilities, and this ultimately empowered me to apply for and achieve a Team Leader position.

I have a successful career/family life and aim to give other chemists the confidence that they can achieve the same.

If you'd like to hear more from inspiring female scientists like Zoë take a look at our upcoming SCItalk on Wednesday 27 September: Women in STEM: Better Science and a Better Workplace for Everyone.

Are you interested in pharmaceutical R&D? Which PhD skills are particularly useful in industry? We asked James Douglas, Director of Global High-Throughput Experimentation at AstraZeneca.

Tell us about your career path to date.

I currently have two roles, firstly as Director of Global High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) within R&D at the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca. I also work one day a week as a Royal Society Entrepreneur in Residence at the Department of Chemistry in the University of Manchester. Both roles involve developing and applying methods and technology in chemical synthesis to facilitate the drug discovery, development, and manufacturing processes.

My journey to these roles began with a chemistry degree and a passion for running chemistry experiments in the laboratory. At the end of my undergraduate MChem degree at the University of York, I spent an amazing placement year at the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline, working in drug development. I then went on to do a PhD at the University of St Andrews and postdoctoral research in the USA, both of which focused on developing new methods for synthesis.

My PhD was in collaboration with AstraZeneca and my postdoc was with the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly, so I knew a lot about medicines R&D and wanted to start a permanent career in that industry.

Pictured above: James Douglas

When did you start working for AstraZeneca?

I started at AstraZeneca in 2015. Initially, I spent most of my time working in the laboratory, supporting drug projects across a range of therapy areas such as oncology, heart disease and respiratory treatment. Since then, I have gradually spent less time in the lab across multiple roles and more time working with – and leading wider teams – with a more company-wide focus.

I have remained closely linked to academic research and universities through collaborative projects. This ultimately led me to the Entrepreneur in Residence role where I am accelerating the translation of chemistry innovation from academia to industry, as well as helping provide students and researchers skills and networks relevant to careers in industry.

What is a typical day like in your job?

I spend about two days a week on site at AstraZeneca in Macclesfield and two working from home. As my main job is office based I can also work from home very easily. It has been this way for me since the start of the pandemic. I missed the general atmosphere of a busy workplace but this period coincided with the birth of my daughter, so I feel lucky to have been able to see a lot more of her growing up than I would have otherwise.

I work with many scientists across the company, not just in Macclesfield, such as in Cambridge (UK), Boston, and Gothenburg, so virtual meetings and calls are a big part of my day. When I’m on site, I prioritise face-to face meetings and discussion with the scientists in the laboratory. Very occasionally I get the chance to run some experiments myself, which I really enjoy.

Since 2022, I have spent Fridays within the Department of Chemistry at the University of Manchester. I talk to academics and PhD students about how their research could be applied in industry, discuss current projects, and think up new ones. I’m also preparing a lecture course and organising careers and networking events to prepare students with skills that are important for careers in industry.

Which aspects of your job do you enjoy the most?

I still get the most excited when faced with the challenge of solving difficult scientific problems. This has changed during my career from working individually in the lab, on relatively clear problems during my PhD, to now being part of much larger teams trying to solve highly complex longer term challenges.

Chemistry is always advancing but so are the standards that we must push towards in drug development – for example, finding ways to shorten the time taken to bring new treatments to patients, while at the same time significantly reducing the environmental impact. That’s a daunting – but exciting – opportunity for synthetic chemists like me.

Most of all, even though the timelines are longer on the projects I work on now, there are moments of short-term success that are exciting. This could be an experimental result from the team that opens up a new possibility, or provides important insight into how best to proceed.

>> Side projects can make large waves. Dr Claire McMullin shares the insights from her journey.

What is the most challenging part of your job?

I miss being able to dedicate my time to experimental work and really understanding a problem in detail. I have spent much of my career investing the large amount of time it takes to understand a problem and think about solutions. Unfortunately, that’s no longer the case and not my main responsibility, but I still find this hard to accept!

I miss the level of detail and discussion I once had and find it a challenge not to spend all my time in the laboratory bothering all the brilliant scientists with questions about what they are doing.

How do you use the skills you obtained during your degree in your job?

Most directly, my degree gave me great general skills in chemistry, ranging from practical experimental techniques to chemical analysis and fundamental principles such as kinetics. These were the basis on which I built more specialised skills in organic synthesis during my PhD and postdoc, all of which are crucial for my career so far.

There are also lots of skills I developed that I didn’t appreciate at the time, such as time management, the ability to think independently, organisation, and teamwork. Like many others, my PhD and postdoc also taught me important lessons about resilience and perseverance.

What advice would you give others interested in pursuing a similar career path?

It’s not advice, but what worked for me was to do what I am passionate about. Don’t worry if it takes a while to work out what that exactly is. I decided to do a chemistry degree mostly because I thought I would enjoy the practical experimental side, which I did and still do. It was only during my final year placement at the pharmaceutical company GSK that I decided to do a PhD so I could learn new areas of chemistry.

Finally, it was only during my postdoc that I decided to try and solve the challenges faced with drug development in industry, rather than the more fundamental undertaken as a research group leader in academia.

I’m still finding out what things interest me and these interests keep changing. That’s the joy of disciplines like chemistry and drug development – there is always so much more to learn and challenges to overcome.

What effect do vaping and air pollution have on your heart, and how could a light-powered pacemaker improve cardiovascular health?

It seems that every day, scientists are learning more about the factors affecting cardiovascular health and are coming up with novel ways to keep our hearts ticking for longer. Here are three interesting recent developments.

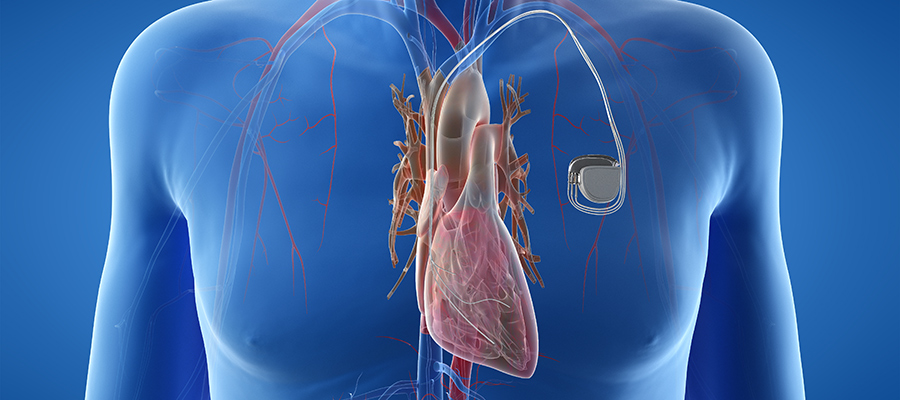

A less painful pacemaker

One of the problems with existing pacemakers is that they are implanted into the heart with one or two points of connection (using screws or hooks). According to University of Arizona researchers, when these devices detect a dangerous irregularity they send an electrical shock through the whole heart to regulate its beat.

These researchers believe their battery-free, light-powered pacemaker could improve the quality of life of heart disease patients through the increased precision of their device.

The way existing pacemakers work can be quite painful for heart disease patients.

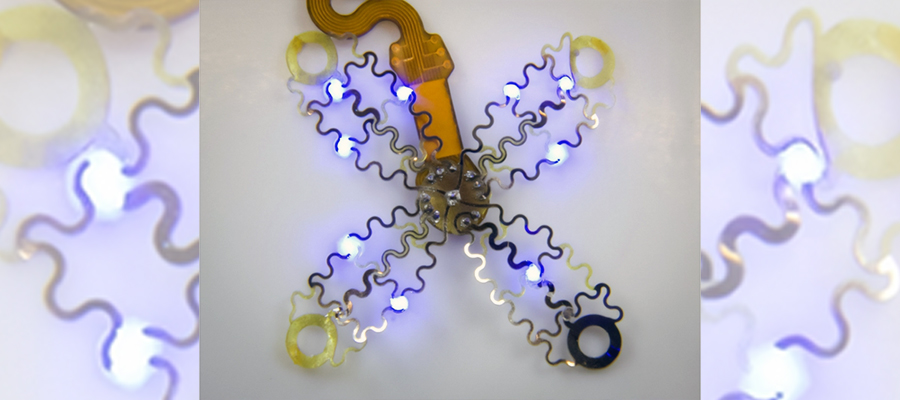

Their pacemaker comprises a petal-like structure made from a thin flexible film (that contains light sources) and a recording electrode. Like the petals of a flower closing up at night, this mesh pacemaker envelops the heart to provide many points of contact.

The device also uses optogenetics – a biological technique to control the activity of cells using light. The researchers say this helps to control the heart far more precisely and bypass pain receptors.

‘Right now, we have to shock the whole heart to do this, [but] these new devices can do much more precise targeting, making defibrillation both more effective and less painful,’ said Igor Efimov, professor of biomedical engineering and medicine at Northwestern University.

‘Current pacemakers record basically a simple threshold, and they will tell you,’ added Philipp Gutruf, lead researcher and biomedical engineering assistant professor. ‘This is going into arrhythmia, now shock, but this device has a computer on board where you can input different algorithms that allow you to pace in a more sophisticated way.’

Another potential benefit is that the light-powered device could negate the need for battery replacement, which is done every five to seven years. That use of light to affect the heart rather than electrical signals could also mean less interference with the device’s recording capabilities and a more complete picture of cardiac episodes.

The device uses light and a technique called optogenetics, which modifies cells that are sensitive to light, then uses light to affect the behavior of those cells. Image by Philipp Gutruff.

>> See how Bright SCIdea winner Cardiatec uses AI to improve heart disease treatment.

The danger of vaping?

We don’t know a lot about the long-term effects of vaping because people simply haven’t been doing it long enough, but a recent study from the University of Wisconsin (UW) suggests that it could be bad for the heart.

Researchers selected a group of people who had used nicotine delivery devices for 4.1 years on average, those who smoked cigarettes for 23 years on average, and non-smokers and compared how their hearts behaved after smoking (the first two groups) and after exercise.

The researchers noticed differences minutes after the first two groups smoked or vaped. ‘Immediately after vaping or smoking, there were worrisome changes in blood pressure, heart rate, heart rate variability and blood vessel tone (constriction),’ said lead study author Matthew Tattersall, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

The lack of long-term data means we still don’t know the effect of vaping.

Those who vaped also performed worse on the four exercise parameters compared to those who hadn’t used nicotine. Perhaps the most startling finding was the post-exercise response of those who had vaped for just four years compared to those who had smoked tobacco for 23 years.

‘The exercise performance of those who vaped was not significantly different from people who used combustible cigarettes, even though they had vaped for fewer years than the people who smoked and were much younger,’ said Christina Hughey, fellow in cardiovascular medicine at UW Health, the integrated health systems of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The influence of lead and air pollution

We know that smoking and passive-smoking are bad for our hearts, but some overlook the effect of other environmental toxins, especially those common to specific geographical regions.

A collaborative study including US and UK researchers has found a divergence in the types of environmental contaminants that contribute to cardiovascular ailments in both countries, aside from the prevalent smoking-related heart disease.

Hopefully, the growth in electric vehicle use will reduce air pollution

The study found that lead-related poisoning is more common in the US, whereas air pollution has a more damaging effect in the UK due mainly to increased population density. The researchers found that 6.5% of cardiovascular deaths were associated with exposure to particulate matter over the past 30 years compared to 5% in the US.

The one plus is that research has found that there has been a steady decline in cardiovascular deaths stemming from lead, smoking, secondhand smoke and air pollution over the past 30 years. Nevertheless, it will be of little comfort to those walking in the trail of exhaust fumes in cities.

‘More research on how environmental risk factors impact our daily lives is needed to help policymakers, public health experts, and communities see the big picture,’ said lead author Anoop Titus, a third-year internal medicine resident at St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Rarely have science and government been as clearly linked as the initial response to the Covid-19 pandemic, when politicians could be heard claiming they were being ‘led by the science’ as often as they could be seen doing that pointing-with-a-thumb-and-fist thing.

This Thursday, the UK’s Chief Scientific Adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, will receive the Lister Medal for his leadership during the Covid-19 pandemic, and you can stream it live here, exclusively on SCI’s YouTube channel!

In readiness for Sir Patrick’s lecture, Eoin Redahan looks back at three ways science helped to mitigate the spread of Covid-19.

People will never look at vaccine development the same way. For good or ill, we have realised just how quickly they can now be developed. Similarly, we have realised what can be achieved when the brightest brains come together. These are two of the positive legacies from Covid.

But there are others. Some of the innovations conceived to tackle Covid will now tackle other pathogens. Here are just three of the innovations that emerged…

1. Wastewater warning

As Oscar Wilde once said: ‘We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking up at the genetic material in stool samples.’

Not many people would find inspiration in wastewater treatment plants when thinking about early warning systems for infectious diseases.

Nevertheless, during the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers at TU Darmstadt in Germany came up with a system that detected Covid infection rates in the general population by analysing their waste – a system so accurate they could detect the presence of Covid among those without recognisable symptoms.

To do this, they examined the genetic material in samples from Frankfurt’s wastewater plants and tested them using the PCR test. They claim that their measurement was so sensitive it could detect fewer than 10 confirmed Covid-19 cases per 100,000 people.

It is inevitable that Covid-19 variants will rise again, but this system could alert us to the need for tighter protective measures as soon as the virus appears in our wastewater.

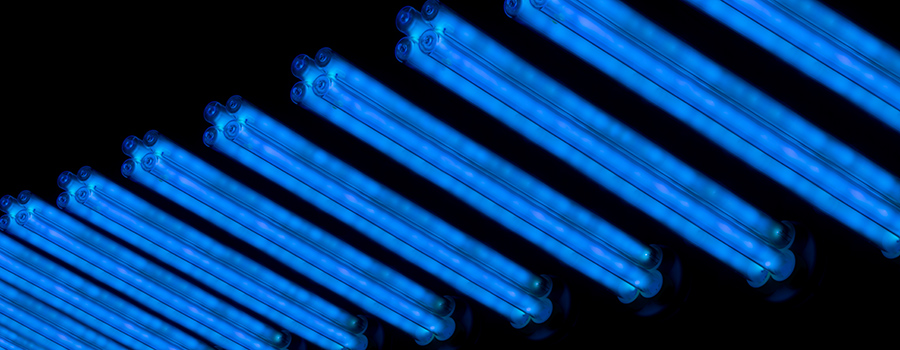

2. UV air treatment

UV light can reportedly reduce indoor airborne microbes by 98%.

Warning systems are important, as are ways to stop the spread of pathogens. To do this, a team from the UK and US shed light on the problem – well, they used ultraviolet light to remove the pathogens.

Using funding from the UK Health Security Agency, Columbia University researchers discovered that far-UVC light from lights installed in the ceiling almost eliminate the indoor transmission of airborne diseases such as Covid-19 and influenza.

The researchers claim it took less than five minutes for their germicidal UV light to reduce indoor airborne microbe levels by more than 98% – and it does the job as long as the light remains switched on.

‘Far-UVC rapidly reduces the amount of active microbes in the indoor air to almost zero, making indoor air essentially as safe as outdoor air,’ said study co-author David Brenner, director of the Center for Radiological Research at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. ‘Using this technology in locations where people gather together indoors could prevent the next potential pandemic.’

3. Biological masks?

‘Physical mask, meet biological mask.’

Many moons ago, it was strange to see a person wearing a mask, even in cities with dubious air quality. Now, they are ubiquitous, and it would appear that mask innovations are everywhere too.

During Covid, researchers from the University of Granada in Spain were aware that wearing masks for a long time could be bad for our health. They devised a near field communication tag for inside our FFP2 masks to monitor CO2 rebreathing. This batteryless, opto-chemical sensor communicates with the wearer’s phone, telling them when CO2 levels are too high.

In the same spirit, researchers in Helsinki, Finland, developed a ‘biological mask’ to counteract Covid-19. The University of Helsinki researchers developed a nasal spray with molecule (TRiSb92) that deactivates the coronavirus spike protein and provides short-term protection against the virus – a sort of biological mask, albeit without those annoying elastics digging into our ears.

‘In animal models, nasally administered TriSb92 offered protection against infection in an exposure situation where all unprotected mice were infected,’ said Anna Mäkelä, postdoctoral researcher and study co-author.

‘Targeting this inhibitory effect of the TriSb92 molecule to a site of the coronavirus spike protein common to all variants of the virus makes it possible to effectively inhibit the ability of all known variants.’

The idea is for this nasal spray to complement vaccines, though during peak Covid paranoia, it might be tricky persuading everyone on the bus that you’re wearing a biological mask.

Covid disrupted scientific progress for many, but as we know, invention shines through in troublesome times. Plenty of innovations such as the ones above will make us better equipped to tackle air borne diseases – alongside the stewardship of leaders like Sir Patrick Vallance.

Watch Sir Patrick Vallance’s talk – Government, Science and Industry: from Covid to Climate – at 18:25 on 24 November

How do you forge a career in process chemistry, and how do you overcome the challenges of studying in your second language? Here’s how Piera Trinchera, Associate Principal Scientist at Pharmaron, found her way.

Tell us about your career path to date.

I am an Associate Principal Scientist in the Process Chemistry department of Pharmaron UK. I am based at the Hoddesdon site in Hertfordshire, where I develop synthetic routes for the manufacture of new drugs for clinical studies.

I’m originally from Italy. I completed my MSci at the University of Salento followed by a PhD in organic chemistry at the University of Bari, focusing on new synthetic methodologies. Despite my complete lack of English at the time, I jumped at the opportunity of a six-month visiting PhD position at the University of Toronto.

This was a challenging experience initially as it was my first time living abroad, but ultimately it was very rewarding. After completing my PhD I returned to the University of Toronto to undertake a postdoctoral position focusing on organoboron chemistry. I followed this with a second postdoc at Queen Mary University of London working on aryne chemistry.

After eight years in academia, I wanted to apply the knowledge I had acquired to solving industrial problems that directly impact people’s lives. For this reason, I joined Pharmaron UK where I have been for the last three years and am currently a project lead and people manager.

What is a typical day like in your job?

I am involved in multiple projects each year and the overall aim is to provide synthetic chemistry solutions for our global clients. Depending on the type of project work, this can include either developing brand new synthetic routes to novel drug candidates or troubleshooting and improving existing chemical processes, making them suitable for large-scale manufacture.

Ultimately, the goal across all projects is the same: to support the production of large quantities of drugs that are needed for clinical studies with a line-of-sight to commercial production.

On a typical working day, I spend the majority of my time in the lab where I conduct my own experiments and lead a team of chemists who work alongside me. I am directly involved in the planning and designing of experiments, execution in the lab, and subsequent manufacture on multi-kg scale in our pilot plant.

Over the course of a project, a large part of the job is communicating to the clients the project strategy, scientific results, and timelines through regular teleconferences, emails, and written reports.

>> Read how side projects made large waves for Dr Claire McMullin

Which aspects of your job do you enjoy the most?

There are many aspects of this job that I enjoy. I have always enjoyed solving new scientific problems, with the thrill of impatiently waiting for the results of an important experiment or the curiosity in trying to understand an unexpected result.

In addition to the science, seeing your day-to-day lab work translated to the production of kg-quantities of new pharmaceutical compounds that might, after clinical studies, further global health is very rewarding.

Projects are completed on much shorter time frames than in academia (three to six months) and there is no time to stagnate as one so often does in a PhD or Postdoc. I enjoy the large breadth in the chemistry and the different challenges that come with each and every project.

Last but not least, it takes many people from different departments (e.g. in analysis, quality assurance, or manufacturing) working closely together to manufacture a drug compound on a kg-scale.

Working so closely with people from different backgrounds has tremendously enriched me during these years in Pharmaron. It has allowed me to acquire new technical knowledge and given me a deeper understanding of not just chemistry but the overall requirements for synthesising pharmaceutical compounds.

What is the most challenging part of your job?

Preparation of a synthetic process for manufacture on a kg-scale involves considerable development in the laboratory to ensure the chemistry translates from small to large scale. Part of this development is to identify potential issues and blindspots of the chemistry and processes and mitigate them by improving the process before implementation on a large scale.

Despite all these efforts, unforeseen complications do occasionally occur on the large scale and finding solutions in real time can be the most challenging aspect of the job. By keeping a clear head, the chemist can leverage both their deep knowledge of the process and the experience of their more senior colleagues to solve these problems.

How do you use the skills you obtained during your PhD and postdocs in your job?

As I’m in a synthetic chemistry job, I have benefitted enormously from the theoretical organic chemistry knowledge and practical laboratory skills that I acquired over the course of my PhD and postdoc years.

Additionally, in academia I became familiar and confident with other skills that I use on a daily basis. These include scientific communication through either written reports or oral presentations, conforming to good laboratory safety practices, and supervising and mentoring other people.

In general, the overall experience of my post-graduate academic education has provided me with the competencies necessary to scientifically manage projects and lead a team in Pharmaron.>> Get involved in the SCI Young Chemists’ Panel.

Which other skills do you need for your work?

Teamwork is a cornerstone of the job and company’s culture. The synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds according to our quality standards would not be possible without the contribution from, and close collaboration among, multiple people across several departments including analytical chemistry, process chemistry, process safety, quality assurance, formulation and manufacturing.

Is there any advice you would give to others interested in pursuing a similar career path?

Don’t be afraid to venture outside of your comfort zone and be open to opportunities, especially those that don’t come along as often. This will help you build your confidence and you will likely find that you can do more than you anticipated. If you are interested in process chemistry, I would recommend looking into internships and/or finding a mentor who can give you an insight into the job.

As with research, perseverance is an important skill you need to master. You will experience failed reactions and difficult purifications at some point in your career as a process chemist. Be open minded, ask questions and don’t be afraid to seek out support from your colleagues.

>> Read how Ofgem’s Dr Chris Unsworth creates an inclusive working environment and transfers his PhD skills.

What does clean smell like? What if the fragrance you want to create is that of a sweet-smelling, yet poisonous, flower? In his Scientific Artistry of Fragrances SCITalk, Dr Ellwood led us by the nose.

When Dr Simon Ellwood spoke about creating a fragrance, it sounded like a musical composition or a painting. The flavourist, sitting before a palette of 1,500 fragrance ingredients. Each occupies a different note on the register: the top notes, the middle ones, and the bottom.

To the outsider, this seems impossibly vast and daunting. The Head of Health & Wellbeing Centre of Excellence – Fragrance and Active Beauty Division at Givaudan mentioned that Persil resolved to come up with ‘the smell of clean’ for its detergents in the late 1950s.

But what should clean smell like? Should it be the green, citrusy aromas of this laundry detergent, the smell of mint, or the antiseptic at the hospital?

To make choosing smells slightly less daunting for flavourists and perfumers, they are at least split into odour families such as citrus, floral, green, fruity, spicy, musky, and woody. Some of these ingredients are natural, some are inspired by nature, and others come from petrochemicals and synthetic materials.

The delicious-smelling musk deer.

Deer gland perfume

One of the smells you may have sprayed on your person – one sibling in this odour family – has peculiar origins. The pleasant, powdery smell known as musk was originally extracted from the caudal gland of the male musk deer and from the civet cat.

But as the Colognoisseur website notes, as many as 50 musk deer would have to be killed to obtain one kilogramme of these nodules. Now, killing a load of deer and cats for a few bottles of perfume may not have seemed unethical several centuries ago, but it also wasn’t sustainable or cost-effective. It became clear that a synthetic musk was needed.

When the synthetic musk discovery came in 1888, it was a chance discovery. Albert Bauer had been looking to make explosives when a distinctive smell came instead, along with the scent of opportunity.

>> Read about the science behind your cosmetics

Dior recreated the woodland notes of Lily of the valley.

Do you like the smell of jasmine?

Dr Ellwood’s talk laid bare not only the vastness of everything we smell, but also the ingenuity of those who recreate these odours. In terms of breadth of smell, neroli oil – which is taken from the blossom of a bitter orange – has floral, citrus, fresh, and sweet odours, with notes of mint and caraway. Similarly, and yet dissimilarly, jasmine’s odour families are broken down into sweet, floral, fresh, and fruity, and – jarringly – intensely fecal.

The ingenuity of flavourists is exemplified by lily of the valley. The woodland, bell-shaped flowers are known for their evocative smell, but all parts of the plant are poisonous. Despite this, French company Dior synthetically recreated the lily of the valley smell in its Diorissimo perfume in 1956 using hydroxycitronellal, which is described by the Good Scents Company as having ‘a sweet floral odour with citrus and melon undertones’.

Cyanide smells like almonds, but you might not want to eat it.

Of course, as Dr Ellwood noted, synthetic flavours can only ever get so close to the real thing – an imperfect facsimile. However, the mere fact that chemists have recreated deer musk, lily of the valley, and the prized ambergris from sperm whales to create the fragrances we love is almost as extraordinary as the smells themselves.

‘Fragrance,’ he said, ‘will always be the confluence of the artistry of the perfumer and the chemist.

Register for our free upcoming SCI Talk on the Chemistry behind Beauty & Personal Care Products.

Do you know how the Academy Awards came to be named the Oscars? What about the story behind the Nobel prize? Behind every award name there is a story, and the Julia Levy Award is no exception.

On the face of it, the Julia Levy Award is about innovation in biomedical applications, but it is the stories of the winners of this SCI Canada award, and Julia Levy herself, that really give it life.

But for a tweak of history, Julia Levy may not have ended up in Canada at all. Born Julia Coppens in Singapore in 1934, she moved to Indonesia in her early childhood. Her father uprooted the family during the Second World War and she left for Vancouver with her mother and sister – her father only joining them after release from a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp.

Julia and her family moved to Vancouver during the Second World War.

After studying bacteriology and immunology at the University of British Columbia (UBC), the young Julia received a PhD in experimental pathology from the University of London. She went on to become a professor at UBC and helped found biopharmaceutical company Quadra Logic Technologies in 1984.

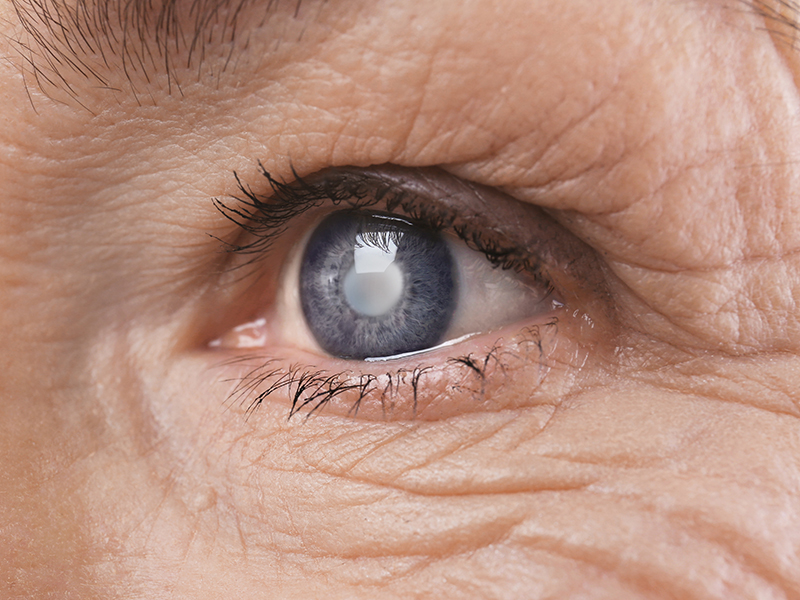

More important than confining her achievements in cold prose, Julia Levy’s work made a profound difference to people’s lives. She developed a groundbreaking photodynamic therapy (PDT) that treated age-related macular degeneration – one of the leading causes of blindness in the elderly. She also created a bladder cancer drug called Photofrin in 1993 and, according to Neil and Susan Bressler, the Visudyne PDT treatment created by Julia and her colleagues was the only proven treatment for certain lesions.

Levy thrived in the business space too, serving as Chief Executive Officer and President of QLT from 1995 to 2001. She has since won a boatload of awards for her achievements, but sometimes the best testimonies come from those who have been inspired by her achievements.

Trailblazing drug discovery systems

For Helen Burt, winner of the 2022 Julia Levy Award and retired Angiotech Professor of Drug Delivery at the University of British Columbia (UBC), Julia has been an inspiration. Here was this UBC professor who jointly founded this big, exciting company – creating medication that improved people’s lives and showing her what was possible.

Helen, an English native, moved to Vancouver in 1976 for her PhD and loved it so much that she stayed. As a professor at UBC, Helen would become a trailblazer in drug delivery systems – a field pioneered earlier by Julia Levy.

‘I was a new assistant professor when she was building Quadra Logic and I would go to talks that she gave,’ Helen said. ‘Essentially, the early technology for QLT was a form of very sophisticated drug delivery [...] It was getting the drug they developed into the eye and irradiating it with light of a specific wavelength.

‘It was very, very targeted. And so, you didn’t get the drug going elsewhere in the body and causing unwanted side effects. So her technology was a form of very advanced drug delivery technology.’

‘For me to win an award that honours Julia Levy and her achievements – I think that's what makes it so special to me.’ – Professor Helen Burt, a former student of Julia Levy, is the Award's most recent recipient.

>> Learn more about SCI Canada.

These talks chimed with the young Helen. If a microbiologist could develop this kind of technology, what was stopping her from developing her own?

She, too, became a pioneer in her field, developing nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems (including those to treat cancer) and a novel drug-eluting coronary stent. According to Professor Laurel Schafer, who put Helen forward for the Julia Levy Award: ‘[Helen] was a trailblazer in new approaches for drug delivery and in research leadership on our campus.’

Importance to Canadian chemistry

Professor Schafer is a hugely accomplished chemist in her own right; and the University of British Columbia chemistry professor’s achievements in catalysis discovery were recognised with the LeSueur Memorial Award at the 2020 Canada Awards.

Julia Levy provided an inspiration to Laurel too, in her case as an exemplar for what Canadian chemists could achieve. ‘The achievements of Julia Levy show that it really can be done right here in Canada, and even right here in British Columbia,’ she said. ‘I grew up in a Canada where I believed that better was elsewhere and our job was to attract better here – a very colonial attitude.

Julia studied at and later became a Professor at the University of British Columbia – the campus is pictured above.

‘I now believe and know that better is right here. Professor Levy’s work showed that world-leading contributions come from UBC and from the laboratories led by women.’

She noted that the Julia Levy Award acknowledges Canadian innovation in health science, whereas Canadian chemistry has historically focused on process chemistry in areas such as mining and petrochemicals.

But Julia Levy’s influence permeates beyond science. ‘Julia is one of those people who has been willing throughout her whole career – even now, well into her eighties – to give back to the community,’ Professor Burt says. ‘She mentors, she coaches, she sits on the boards of startup companies, and she advises.’

‘She’s just got this incredible amount of knowledge… She was the Chief Executive Officer [at QLT], so she learnt all of the aspects: the complex and sophisticated regulations, knowing how to find the right people to conduct clinical trials, and how to do the scale-up. She really is a legend in terms of giving back to the community. And this is not just in British Columbia – it’s Pan-Canadian.’

Pictured above: Julia Levy

For young chemists, the Julia Levy in the Julia Levy Award may just be a name for now, but for those in the Canadian chemical industry and patients all over the world, her influence and her work resonate.

As Professor Helen Burt said: ‘For me to win an award that honours Julia Levy and her achievements – I think that's what makes it so special to me.’

>> For more information on the Canada Awards, go to: https://bit.ly/3VMwNKa

Little machines that blend makeup tailored for your skin alone… Technology that details the tiny creatures walking on your face… The cosmetic revolution is coming, and Dr Barbara Brockway told us all about it.

Max Huber burnt his face. The lab experiment left him scarred, and he couldn’t find a way to heal it. So, he turned to the sea. Inspired by the regenerative powers of seaweed, he conducted experiment after experiment – 6,000 in all – until he created his miracle broth in 1965. You might know this moisturiser as Crème de la Mer.

A rocket scientist in the world of cosmetics seems strange, but when you interrogate it, it isn’t strange at all. As Dr Barbara Brockway, a scientific advisor in cosmetics and personal care, explained in our latest SCItalk, cosmetics hang from the many branches of science.

Engineering, computer science, maths, biology, chemistry, statistics, artificial intelligence, and bioinformatics are among the disciplines that create the creams you knead into your face, the sprays that stun your hair in place. They say it takes a village to raise a child, and it takes an army of scientists to formulate all the creams, gels, lotions, body milks, and sprays in your cupboard.

Some say sea kelp can be used to treat everything from diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer, to repairing your nails and skin.

There is a reason why the chemistry behind these products is so advanced. If you sell bread, it is made to last a week. If you make a moisturising cream, it is formulated to last three years. To make sure it does that, chemists test it at elevated temperatures to speed up the time frame. They conduct vibration tests and freeze-thaw tests to measure its stability.

Dr Brockway likened the process of bringing a product to market to a game of snakes and ladders. If you climb enough ladders, you could take your own miracle brew to market within 10 months.

But expectations are high, and the product must delight the user. Think of the teenager who empties a half a can of Lynx Africa into his armpit, or the perfume that is a dream inhaled. Each smell she likened to a musical composition.

But these formulators are not struggling artists. Perfumers and cosmetic chemists – these bottlers of love and longing and loss – can earn a fortune. Dr Brockway’s quick calculation provided a glimpse of the lucre.

Take 15kg of the bulk cream you mixed on your kitchen table. That same cream could be turned into 1,000 15ml bottles, each sold for £78. So, just 15kg of product could fetch £78,000. So, it’s easy to see why the global beauty market is worth $483 billion (£427 billion), with the UK market alone worth £7.8 billion – more than the furniture industry.

Smart mirror, mirror, on the wall…

It’s unsurprising that an industry of such value and scientific breadth embraces the latest technologies, from those found in our phones to advances in genetics and the omics revolution.

Already, the digital world has left the makeup tester behind. Smart mirrors overlay virtual makeup, recommend products for your complexion, and even detect skin conditions. Small machines that look like coffee-makes blend bespoke makeup. Indeed, Dr Brockway noted that Yves Saint Laurent has created a blender that produces up to 15,000 different shades.

Even blockchain has elbowed into the act. It is being used to make sure that a product’s ingredients aren’t changed in between batches. By showing customers every time-stamped link of the supply chain, companies can prove that their products are organic or ethically sourced. The reason why blockchain is significant here is that, once recorded, the data stored cannot be amended.

At first glance, proving the provenance of materials to customers might seem like a marketing ploy, but this is also being done in response to the increasing fussiness of the consumer.

Collagen is the main component of connective tissue.

Dr Brockway said all brands are now under pressure to incorporate sustainability into their business practices. The younger age group is also looking for more organic, vegan-friendly ingredients, and businesses have had to respond.

For example, microbial fermentation is being used instead of roosters’ coxcombs to create hyaluronic acid. Similarly, Geltor claims to have created the first ever biodesigned vegan human collagen for skincare (HumaColl21®). Such collagen is usually provided by our friends the fish.

These advances are significant, certainly to the life expectancies of roosters and fish, but of such ingredients revolutions are not made. Other forces will shake the industry.

Meditating on omics

Back in the 1970s, scientists thought the microbes that live on our skin were simple, but next-generation DNA technology reveals that thousands of species of bacteria live on our skin (a pleasant thought). Dr Brockway says these microbes tell us about our lifestyles – to the point that they even know if you own a pet.

So, what is the significance of this? Developments in DNA technology and omics (various disciplines in biology including genomics, proteomics, metagenomics, and metabolomics) mean we can now get not just a snapshot, but an entire picture of what’s going on on your face.

‘Thanks to omics we really know what’s now going on with our skin and see what our products are doing,’ Dr Brockway said. ‘We know the target better. We know which collagens, out of the 263, we need to encourage.’

We are learning more and more about how our skin behaves. And those time-honoured potions and lotions espoused by our grandparents – it will make sense soon, not just why they work, but why they work for some and not for others. In cosmetics, we are leaving the era of checkers and entering the age of chess.

This is the first of three cosmetic SCItalks between now and Christmas. Register now for the Scientific artistry of fragrances.

Reading outside his research area and efficient chemistry helped 2022 Perkin Medal winner Dennis Liotta develop groundbreaking drugs.

There has been an explosion of statistics in football, but one of the most influential figures in this revolution, Ramm Mylvaganam, didn’t care for the game. He worked for the confectionary company Mars. He sold chairs. He knew nothing about football.

However, this key figure outlined in Rory Smith’s recent book, Expected Goals: The story of how data conquered football, came into the field of football analysis and changed the game forever – partly because he approached the game with the fresh perspective of the outsider.

So, what do football statistics have to do with a chemist who came up with life-saving medications? Well, Dr Dennis Liotta, who came up with AIDS antivirals that have saved thousands of lives, may not have entered medicinal chemistry as a complete outsider. He was a chemist, after all. However, like Ramm Mylvaganam, his broad breadth of knowledge from different areas gave him a unique perspective on a new field.

Reading at random

Dr Liotta didn’t take the standard path into medicinal chemistry. In fact, he wasn't a diligent chemistry student at first – and that, in an odd way, contributed to his later success.

For the first couple of years at university, he was more interested in his extracurricular activities; but in his third year, he realised he needed to catch up. He worked hard and burnt the midnight oil. He also did something unusual.

‘I did something that’s kind of ridiculous-sounding,’ he said. ‘I had this big fat organic chemistry book, and I would just open it up randomly to some page and read 10 or 12 pages and close it back up. Over time, I ended up covering not only the things I missed, but actually learning about a lot of things that wouldn't have been covered.’

As his career progressed, Dr Liotta realised the importance of not just working harder, but working smarter. On Sundays, he would sit down with a bunch of academic journals to stay abreast of developments. However, as he read them, he discovered other papers – ones outside his research area – that piqued his interest.

Dennis Liotta in one of his lab spaces at Emory. Image by Marcusrpolo.

‘I’d see something intriguing. And so I’d say, that’s interesting, let me read. I started learning about things that I didn’t technically need to know about, because they were outside of my immediate interest. But those things really changed my life. And, ultimately, I think they were the differentiating factor.’

The intellectual stretch

This intellectual curiosity led to more than 100 patents, including a groundbreaking drug in the fight against AIDS that is still used today and a hand in developing an important hepatitis C drug.

‘In science, many times the people who actually make the most significant innovations are the people who come at a problem that’s outside of their field,’ Dr Liotta said. ‘Without realising it, we all get programmed in terms of how we think about problems, what we accept as fact.’

‘But when you come at a problem that’s outside your field… you aren't immersed in it. So, you think about the problems differently. And many times, in thinking about the problems differently, you’ll come up with an alternative solution that people in the field wouldn’t.’

We’ve often heard the stories of Steve Jobs wandering into random classes while at university when he should have been attending his actual course. Apparently, a calligraphy class inspired the font later used in Apple’s products. In other words, early specialism can sometimes hinder creativity.

‘I've looked into people who have made really some amazing contributions, and many times there’s been an intellectual stretch,’ Dr Liotta said. ‘They’ve gone out there and done something that they weren’t really trained to do. You can fall on your face from time to time, but it’s really nice when we're able to make contributions in areas where we don’t really have any formal training.’

Chance favours…

Of course, there’s so much more to creating life-saving drugs than intellectual curiosity and a different way of thinking. Dr Liotta and his colleagues had the technical skill to turn their ideas into something real. He was a skilled chemist who teamed up with an excellent virologist, Raymond Schinazi. The result of this blend of their skills gave them an edge over others developing AIDS therapeutics.

Dr Liotta invented breakthrough HIV drug Emtricitabine.

‘The very first thing we did was we figured out a spectacular way of preparing the compounds – very clean, very efficient,’ he said. ‘And that [meant we could] explore all sorts of different permutations around the series of compounds that others couldn’t easily do, because their methods were so bad for making [them].

‘So, even though we were competing against some very important pharmaceutical companies that had infinitely more money than we had – dozens of really smart people they put on the project – we were able to run circles around them because we had a really efficient methodology and that enabled us to make some compounds.’

The amazing thing is that the very first compound and the third compound the pair came up with led to FDA-approved drugs. It is a fine thing, indeed, when skill and serendipity meet.

‘Chance favours the prepared mind,’ Dr Liotta said, ‘or, as my colleagues say: you work hard to put yourself in a position to get lucky.’

>> Learn more about Dr Liotta’s career path and research from our recent Q&A.

From luminescent polymer nanoparticles that improve rural healthcare to compostable plastic packaging, Dr Zachary Hudson and his research group at the University of British Columbia are developing solutions to pressing issues.

For those of us who live in cities, we take easy access to hospitals for granted, but what about those in remote areas? What if there were an easier way to diagnose diseases and improve healthcare for those in secluded rural areas?

Luminescent dyes used to make fluorescent Pdots.

Well, Dr Zachary Hudson and his group at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada are developing luminescent polymer nanoparticles that could provide portable, low-cost tools for bio-imaging and analysis in rural areas. These nanoparticles are so bright that they can be detected by smartphone, helping clinicians quantify chemical substances of interest such as cancer cells.

Dr Hudson’s work spans other areas too, including working with industry to develop compostable plastics and ongoing research in opto-electronics. His creativity in applied polymer science was recognised recently with the 8th Polymer International-IUPAC award, organised by SCI, the Editorial Board of Polymer International, and IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry).

We caught up with Zac to ask about these luminous Pdots, compostable plastics, and how it felt to be recognised by his peers.

Dr Zachary Hudson

Tell us about the nanoparticle and remote diagnostic technologies you are developing to boost rural healthcare.

Our group is working with Professor Russ Algar, an analytical chemist at UBC, to develop fluorescent nanoparticles that are bright enough to be detected by a handheld smartphone camera.

The concept is to design nanoparticles that can quantify biological analytes of interest, such as cancer cells or enzymes, and provide a signal that a smartphone can measure. In this way, we hope to create portable, low-cost tools for bioanalysis for use in remote or low-income regions.

Why is the capacity to conduct remote diagnostics so important for those in remote areas?

Coming from Vancouver, I have ready access to sophisticated lab facilities and hospitals that are only a short distance from where I live. This gives me access to some of the world’s most advanced techniques in molecular medicine with relative ease.

For most of the world’s population, however, geography or resources limit their access to these advanced tools that can have a real, positive impact on human health. Expanding access to molecular diagnostic technologies can help more people get the diagnosis they need without a dedicated lab.

How did the ideas for the Pdots come about?

We became interested in Pdots due to Professor Algar’s groundbreaking work using quantum dots for smartphone-based bioanalysis. We learned that by tapping into the versatility of polymer chemistry, we could create polymer nanoparticles, or Pdots, that combined many advanced functions into a single particle.

>> From Covid-19 to the two World Wars, how has adversity shaped innovation? We took a closer look.

How have you worked with other partners to turn these ideas into a reality?

We are currently planning a major initiative with rural health organisations in British Columbia to help move these tools toward practical use. Stay tuned for more info!

You’ve also worked with local industry to reduce the use of single-use plastics. How have you gone about this?

There has been a major push in Canada to reduce the consumption of single-use plastics, and many companies are currently developing new products to respond to this need. Our lab has worked with local industry to formulate and test compostable plastics that can act as substitutes for petroleum-based plastics in consumer packaging.

The Nexe Pod, a fully compostable, plant-based coffee pod created by NEXE Innovations, with Zac as Chief Scientific Officer, received a $1m funding grant from the Canadian government in 2021.

You’ve helped develop compostable materials. How tricky is this from both a material and an environmental perspective?

Compostable plastics are challenging for a few reasons: the demand for them is skyrocketing, so robust supply chains are needed to help companies get away from petroleum feedstocks. The regulatory framework around compostable plastics also varies widely by country, which poses challenges for international commercialisation.

Finally, most machinery for the high-speed manufacturing of plastic packaging is highly optimised for petroleum-based plastics, so new equipment and techniques that are suitable for processing compostable plastics need to be developed alongside the plastics themselves.

>> Do you work in pharmaceutical development? Check out our upcoming events.

What’s next for these innovations, and are you working on anything else interesting?

I've spent most of my career working on light-emitting materials for display technologies and bioimaging, and we’ve recently learned that many of these same materials make useful photocatalysts with applications in the pharmaceutical industry.

We recently partnered with Bristol Myers Squibb to develop all-organic photocatalysts with performance on par with some of the expensive iridium-based catalysts that industry is currently using. I'm looking forward to developing this area further.

What was it like to win the 8th Polymer International-IUPAC award for Creativity in Applied Polymer Science?

It was a great feeling to have our group’s work recognised by the international polymer community. The award lecture at the IUPAC conference also gave us the perfect venue to highlight some of the research directions I’m most excited about in the years ahead.

Those with the blood group O reportedly have the lowest likelihood of catching Covid-19, and the new top-up jab should provide relief against sub-variants of the disease.

By now, most of us have been stricken by Covid, but 15% of people in the UK have evaded the virus. According to a testing expert at the London Medical Laboratory, the great escape is down to three factors: blood group, vaccines, and lifestyle.

Having assessed the findings of recent Covid-19 blood type studies, Dr Quinton Fivelman PhD, Chief Scientific Officer at London Medical Laboratory (LML), believes that people with the blood group O are less likely to be infected than those with other blood groups, while those with blood type A are far more likely to contract the virus.

‘There have now been too many studies to ignore which reveal that people have a lower chance of catching the virus, or developing a severe illness, if they have blood group O,’ he said.

Indeed, research from the New England Journal of Medicine had previously found that those with blood type O were 35% less likely to be infected, whereas those with Type A were 45% more vulnerable. A further benefit of type O blood is the reduced risk of heart disease compared to those with type A or B blood.

>> What is the ideal body position to adopt when taking a pill? Wonder no more.

Staged stock images are not thought to increase your chances of contracting Covid-19.

According to the NHS, almost half of the population (48%) has the O blood group; so, clearly, other factors come into play in terms of our susceptibility. Dr Fivelman said: ‘By far the most important factor is the number of antibodies you carry, from inoculations and previous infections, together with your level of overall health and fitness.’

Tackling the sub-variants

So, those who are more careful about visiting crowded places, who eat well, and are fortunate enough not to have an underlying illness have better chances of avoiding Covid-19. According to LML, having been vaccinated also helps, though these benefits have slowly worn off. That is why the new top-up jab with the Omicron variant could provide some relief for those who take it.

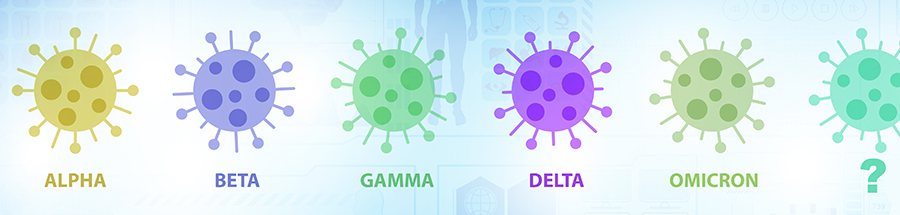

‘The new Omicron jab has come none-too-soon, so many people are now suffering repeated Covid infections,’ he added. ‘That’s because the new Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 sub-variants do not produce as high an immune response as the previous strains, so re-infection is more likely to occur.

‘Higher levels of antibodies are important to neutralise the virus, stopping infection and limiting people transmitting the virus to others.’

>> Which herbs could boost your wellbeing? Dr Vivien Rolfe tells us more.

In her winning essay in SCI Scotland’s Postgraduate Researcher competition, Rebecca Stevens, Industrial PhD student with GSK and the University of Strathclyde, talks about the potential of PROTACS.

Each year, SCI’s Scotland Regional Group runs the Scotland Postgraduate Researcher Competition to celebrate the work of research students working in scientific research in Scottish universities.

This year, four students produced outstanding essays in which they describe their research projects and the need for them. In the third of this year’s winning essays, Rebecca Stevens discusses her work in developing a multistep synthetic platform for Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTAC) synthesis and the potential of PROTACS in general.

Pictured above: Rebecca Stevens

A ‘PROTAC-tical’ synthetic approach to new pharmaceutical modalities

PROTACs are a rapidly evolving new drug modality that is currently sparking great excitement within the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries.

Despite the first PROTAC only being reported in 2001, 12 of these potential drugs have already entered phase I/II clinical trials. In fact, a handful of new biotechnology companies have launched in the last two decades with a primary focus on these molecules. So, what’s so special about them?

Traditional drug discovery relies on optimising small-molecules to inhibit the action of a protein target and subsequently elicit a downstream effect on cellular function. However, many proteins are not tractable to this approach due to their lack of defined binding sites. This is where PROTACs offer a unique opportunity to target traditionally ‘undruggable’ parts of the proteome; instead of inhibiting the protein, PROTACs simply remove it altogether.

PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules made up of two small-molecule binders attached together via a covalent linker; one end binds to the protein of interest and the other to an E3 ubiquitin ligase.

Rebecca is working on a multistep platform for PROTAC synthesis.

By bringing these two proteins into close proximity, PROTACs exploit the body’s own protein degradation mechanisms to tag and degrade desired proteins of interest in a method known as ‘targeted protein degradation’.

This different mechanism of action offers some revolutionary advantages over small-molecule drugs. Alongside potentially accessing ‘undruggable’ targets, PROTACs can overcome resistance mechanisms from which other drugs suffer, as well as acting in a catalytic manner, ultimately requiring less compound for therapeutic effects and maximising profits.

>> SCI’s Scotland Group connects scientists working in industry and academia throughout Scotland.

Problems with PROTACS

While great in theory, the reality is that with two small-molecule binders and a linker, PROTACs are typically double the size and complexity of normal drugs, so their synthesis is far from simple.

Classic drug discovery programmes often make many bespoke analogues alongside their use of library synthesis, using a design-make test cycle to optimise hits and find a lead molecule. With PROTACs, linear synthetic routes are much longer for bespoke compounds, underlining an even greater need for new PROTAC parallel synthesis platforms.

>> Read Marina Economidou’s winning essay on palladium recovery

Additionally, the design of PROTACs is more challenging as there are three separate parts of the structure to optimise, and small changes can have a large impact on their biological activity. As such, very simple chemistry is used to connect the three parts of the molecule, resulting in limited chemical space for exploration, causing potentially interesting bioactive compounds to be missed.

A platform for PROTAC synthesis

My PhD project seeks to develop a multistep synthetic platform for PROTAC synthesis, using modern chemical transformations such as C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-couplings and metallaphotoredox chemistry.

Starting from already complex intermediates in the synthetic route, methods for late-stage functionalisation are under development to complete the final synthetic steps. By making elaborate changes at a late stage, a variety of structurally diverse PROTACs can be synthesised from a single building block, offering an economical and sustainable approach to optimisation for the industries involved.

Furthermore, the purification step prior to testing will be eliminated, with crude reaction mixtures taken into cells in an emerging ‘direct-to-biology high-throughput-chemistry’ approach. This removes a key bottleneck associated with hit identification and lead optimisation, delivering biological results in very short turnaround times.

The synthetic methods developed in the project will offer new capabilities for efficient and sustainable synthesis of PROTACs and other related modalities. Increasing the pace of data generation could accelerate the exploration of structure-activity relationships and deployment in large parallel arrays could provide a significant quantity of data to inform new machine learning models.

Ultimately, for industry, this ‘PROTAC-tical’ approach offers a huge opportunity for rapidly progressing PROTAC projects and discovering novel PROTACs with clinical potential.

>> Our Careers for Chemistry Postdocs series explores the different career paths taken by chemistry graduates.

What is the best posture to adopt when taking a pill, and why does it help your body to absorb the medicine quicker?

Was Mary Poppins wrong? A spoonful of sugar may help the medicine go down, but does it do so in the most delightful way? Not according to Johns Hopkins University researchers in the US.

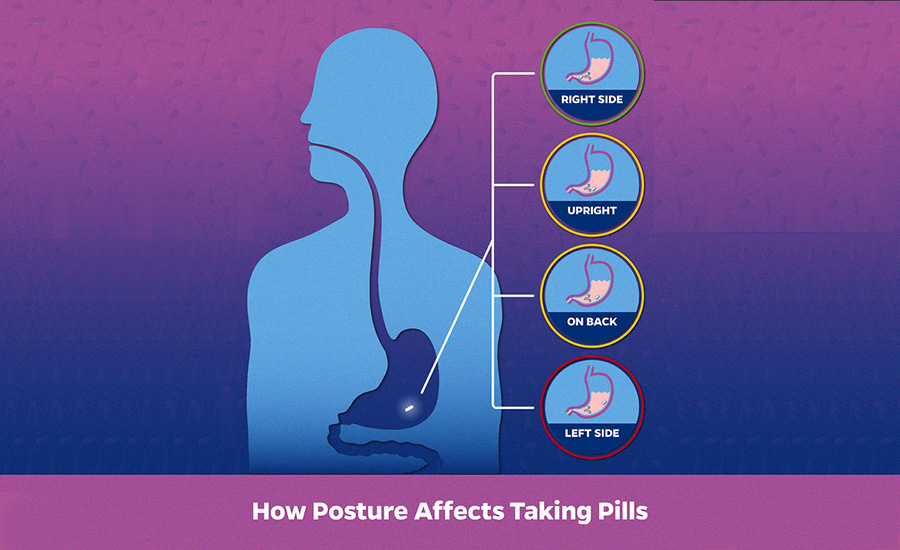

They say the body posture you adopt when taking a pill affects how quickly your body absorbs the medicine by up to an hour. It’s all down to the positioning of the stomach relative to where the pill enters it.

The team identified this after creating StomachSim – a model that simulates drug dissolution mechanics in the stomach. The model works by blending physics and biomechanics to mimic what’s going on when our stomachs digest medicine and food.

Standing up, on your back, or by your side?

Looks like we’ve got a pro here.

Without further ado, here are the four contenders for taking the pill: standing up, lying down on your right side, lying down on your left side, and swallowing the pill on your back.

>> What’s next in wearables? We looked at a few Bright SCIdeas.

According to the researchers, if you take a pill while lying on your left side, it could take more than 100 minutes for the medicine to dissolve. Lying on your back is next in third, the narrowest of whiskers behind swallowing a pill standing up. This time-honoured method takes about 23 minutes to take effect.

However, by far the most effective method (and, therefore, the most delightful way) is lying on your right side, with dissolution taking a mere 10 minutes. The reason is that it sends pills into the deepest part of the stomach, making it 2.3 times faster to dissolve than the upright posture you’re probably taking to swallow your multi-vits.

Your posture is key in ensuring your body absorbs medicine quickly. Image: Khamar Hopkins/John Hopkins University.

‘We were very surprised that posture had such an immense effect on the dissolution rate of a pill,’ said senior author Rajat Mittal, a Johns Hopkins engineer. ‘I never thought about whether I was doing it right or wrong but now I’ll definitely think about it every time I take a pill.’

Next week, we will investigate more of the medical approaches espoused by much-loved fictional characters, starting with George’s Marvellous Medicine, before moving onto the witches in Macbeth. No one is safe.

In the meantime, you can read the researchers’ work in Physics of Fluids.

In her winning essay in SCI Scotland’s Postgraduate Researcher competition, Marina Economidou, first year PhD Student at GSK/The University of Strathclyde, talks about palladium recovery.

Each year, SCI’s Scotland Regional Group runs the Scotland Postgraduate Researcher Competition to celebrate the work of research students working in scientific research in Scottish universities.

This year, four students produced outstanding essays in which they describe their research projects and the need for them. In the second of this year’s winning essays, Marina Economidou explains the need for palladium recovery and making it more efficient.

Pictured above: Marina Economidou

U-Pd-ating the workflows for metal removal in industrial processes

Palladium-catalysed reactions have great utility in the pharmaceutical industry as they offer an easy way to access important functional motifs in molecules through the formation of carbon-carbon or carbon-hetero-atom bonds.

The superior performance of such reactions over classical methodologies is evident in modern drug syntheses, where Buchwald-Hartwig, Negishi or Suzuki cross-coupling reactions are frequently employed.

However, the demand for efficient methods of palladium recovery runs parallel to the increased use of catalysts in synthesis. The interest in metal extraction can be attributed to several reasons.

Cross-coupling steps are usually situated late in the synthetic route, resulting in metal residues in the final product. In addition to possessing intrinsic toxicity, elemental impurities can have an unfavourable impact on downstream chemistry.Hence, their limit must be below the threshold set by the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH).

The need for palladium recovery

However, the importance of palladium recovery does not only arise from the need to meet regulatory criteria. The volatility of palladium supply as a result of geopolitical instabilities has been a focus of attention this year, with Russia producing up to 30% of the global supply and prices reaching an all-time high of £81,179 per kilogramme.

Therefore, aside from the need to remove metals from the product for regulatory reasons, there is a desire to recover metals from waste streams as effectively as possible due to their finite nature and high costs.

The sustainability benefits of recovery for circular use are an additional incentive for an efficient extraction process, as catalysts can be regenerated when metal is returned to suppliers.

The increasing pressure for greener processes and more ambitious sustainability goals – such as GlaxoSmithKline’s environmental sustainability target of net zero impact on climate by 2030 – also contribute to the need for further refinement of working practices.

>> SCI's Scotland Group connects scientists working in industry and academia throughout Scotland.

Palladium has many uses including in catalytic converters, surgical instruments, and dental fillings.

Improving extraction processes

It is essential to have well-controlled and reproducible processes for pharmaceutical production, as redevelopment requires further laboratory work and additional time and resources.

With several industry reports on the inconsistent removal of palladium following catalytic synthetic steps, there seems to be a knowledge gap as to which factors affect the efficiency of extraction and why there can be significant differences between laboratory and plant conditions.

The focus of my PhD is investigating the speciation of palladium in solution in the presence of pharmaceutically relevant molecules, to offer an insight into the efficiency of metal extraction at the end of processes.

By understanding the oxidation state and coordinative saturation of the palladium species formed in the presence of different ligands, a better relationship could be established between the observed performance of metal extraction processes under inert and non-inert conditions.

With the wide breadth of ligands and extractants that are now commercially available for cross-coupling reactions, my ambition is to generate a workflow for smart condition selection that not only achieves selective metal recovery, but is scalable and can be transferred to plant with consistent performance.

The cost and preciousness of metal catalysts are both factors that prohibit their one-time use in processes. Understanding how palladium can be extracted and recovered in an efficient manner will not only deliver reliable processes that meet the demands of the market in the production of goods, it will also lead to economic and environmental benefits.

>> Read Angus McLuskie’s winning essay on replacing toxic feedstocks.

>> Our Careers for Chemistry Postdocs series explores the different career paths taken by chemistry graduates.

From the Black Death to the Covid-19 pandemic, great adversity has also led to great advances. So, which inventions have emerged from times of hardship? Eoin Redahan finds out.

‘World events shape innovations. The World Wars shaped innovation, and the pandemic has shaped innovation,’ said Paul Booth OBE, in his outgoing speech as SCI President.

‘It is possible to accelerate innovation – we’ve demonstrated that.’ Paul Booth OBE, outgoing SCI President at SCI’s AGM, July 2022. Image: SCI/Andrew Lunn

The pandemic taught us a lot about ourselves. It taught me that eating my body weight in sweets was a great way to destroy my teeth, and it brought home to many the futility of the five-day commute. On a more abstract level, it taught governments and policy makers just how much can be achieved in a short space of time when necessity demands it. The vaccines that swam around our veins bore testament to this.

The pandemic has shaped innovation. Nowhere is this more apparent than in medicine. It isn’t the first awful event to provide a hotbed for change, and it won’t be the last. ‘It is possible to accelerate innovation,’ Paul said. ‘We’ve demonstrated that.’

Black Death and the bird mask

As bad as the Covid-19 pandemic was, the Black Death makes it look very tame indeed. It is estimated that the Plague, which was its worst from 1346-53, took up to 200 million lives in Eurasia and North Africa.

Amid the carnage, it is also said to have given us a system to mitigate infectious diseases with which we are familiar, including isolation periods. According to Britannica, ‘public officials created a system of sanitary control to combat contagious diseases, using observation stations, isolation hospitals, and disinfection procedures.’

The terrifying doctor will see you now.